The Piirto Pyramid

of Talent Development

A Model by

Jane Piirto, Ph.D.

Sisu Press

All Rights Reserved

© Jane Piirto, Ph.D. 1994/2011

THE PIIRTO PYRAMID OF TALENT DEVELOPMENT:

A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR CONSIDERING TALENT

“The ‘Pyramid’ is excellent—a compact, eloquent, graphic synthesis.” — Frank Barron (one of the original creativity researchers)

“Her original model situates Piirto within the field of talent development and creativity as a force to be reckoned with.” –Kimberly McGlonn-Nelson in a review of Understanding Creativity

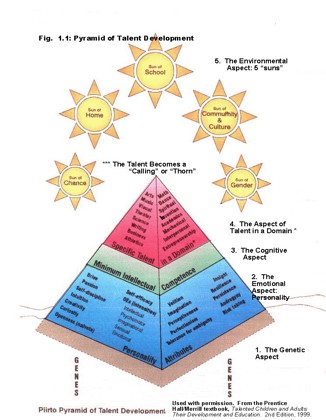

ABOUT THE PIIRTO PYAMID OF TALENT DEVELOPMENT

The Piirto Pyramid is a model which takes into account genetics, personality, IQ, talent, and environmental influences that are essential in developing talent. It is a model widely known in education and psychology. This article describes the Piirto Pyramid and gives examples from the areas of visual arts, creative writing, music, theater, dance, science, mathematics, invention, entrepreneurship, and athletics, of common themes in how talent is development in each area. It is a contextual framework that considers the 4 P’s of creativity— person, process, and product, as well as press, or environmental factors. I published my first version of the Piirto Pyramid in 1994. Over the years it has evolved thanks to talks and critiques from friends, students, and colleagues. This model has guided work on talent in domains. I have published quite a few articles and chapters, as well as books, using this model. See the reference list, below. Piirto (1994; 1995a, b; 1998; 1999a; 2001; 2004, 2007, 2008; 2009; 2010; 2011).

THE PIIRTO PYRAMID OF TALENT DEVELOPMENT

To put it simplistically, there are several ways to approach creativity. Creativity research focuses on the PERSON– who is creative? The PROCESS — what happens when one is being creative?; the PRODUCT — what does the creative person make?; and the PRESS– what is the environmental pressure on person, process, product (Richards, 1999)? One judges a product “creative” and then looks at the person who has produced that product, to see what forces operated in the creation of that product, what that person is like. Another approach tests a child through paper and pencil or through observation, pronouncing him or her potentially or really more creative than others, on a presumed normal curve of creativity, as a construct, which supposedly exists within everyone to some degree or another. My approach has been to look at the creative person, and the creative press. I am, in this book, summarizing the findings in my books, Talented Children and Adults: Their Development and Education (Piirto, 1994, 1999, 2007), Understanding Those Who Create (Piirto, 1992/1998), and Understanding Creativity (Piirto, 2004). Persons who have produced creative products — visual artists, creative writers, creative mathematicians, creative scientists, mathematicians, entrepreneurs, architects, performing artists, musicians, inventors—have certain patterns in their lives. What are their backgrounds, their personalities, their experiences, and their ways of looking at the world?

When one looks at the development of talent, one notices certain patterns that are common to those who enter the same field. In my book Talented Children and Adults (1994; 1999; 2007), I call these predictive behaviors, for even early in life, practitioners of creativity in a specific domain have undertaken certain practices that are common for people who practice creating in that domain.

Along with these predictive behaviors are certain crystallizing experiences. Crystallizing experiences are unique to the individual, while predictive behaviors are common to the domain. The crystallizing experience lets the person know that this domain is the one for him and sets him on the path. I have confirmed the presence of these predictive behaviors through noting the repetition of the pattern: over the past years, several hundred of my students have conducted biographical studies of creators in the domains of visual arts, creative writing, science, mathematics, invention, entrepreneurship, music, theater, dance, drama, and athletics. The assignment has been to compare and contrast the person about whom the biographical study was written with the commonalities I found in the lives of these creators in certain domains. To a surprising degree, the students have found that the paths are similar. “Find a writer who didn’t have a predictive behavior of voracious and uncritical reading,” I challenge them.” “Find a scientist who was not, from an early age, rabidly curious about the meaning of life.”

HISTORY OF THE PIIRTO PYRAMID

In 1992, after reading almost all the research extant about talented, gifted, and creative children and adults, for the publication of my synoptic textbook Talented Children and Adults, for Macmillan, My editor told me that in completing it, I had a choice. I could formulate a theory of what talent development entails, or I could just just summarize and stop. Being somewhat of a risk-taker, I decided to formulate a theory based on what I had read. “What have I learned?” “What have I learned?” “What are the common threads of talent development and creativity?” The fact that few women had made theories of creativity and talent development only made me more determined to take the risk.

I was driving to my newly married daughter’s home in Brooklyn, New York, from my home in Ohio. As I sailed along Interstate 80 through the beautiful Pennsylvania countryside, I asked myself over and over again, “What have I learned?” “What have I learned? Driving on a peaceful interstate fed my creative thoughts; indeed, such half-trance is important in the creative process. (I have written about the creative process in my books Understanding Those Who Create, Understanding Creativity, and Creativity for 21st Century Skills, as well as in many chapters and articles.) The insight came to me. It’s personality that’s important in talent development, and not IQ, I thought. It’s personality!”

That night, in steamy August, sleeping on the newly carpeted sticky hot floor of my daughter’s apartment on a clammy sleeping bag, I had a dream. “It’s personality,” the dream echoed, from my insight on the freeway earlier that day. “It’s personality that affects the most. Not test scores. Personality.” I got up and in the middle of the night, sketched a first draft of the ideas I had insight about; it was a picture of Greek gods and goddesses representing various personality attributes, as in mythology (Athena is aggression; Apollo is insight, etc.) shooting darts and arrows (not of outrageous fortune, though). The image was confusing, and I went back to the thinking board/ the image board. How would I convey what I had gleaned about the development of talent in individuals? I finally settled on the pyramid image, which is universal and used in many theories. The environmental suns and the genetic underground were also part of the image. In making a theory, it is essential to be clear and simple.

The following are the basic assumptions of the Piirto Pyramid

1. Creativity is domain-based.

2. Environmental factors are extremely important in the development of talent.

3. Talent is an inborn propensity to perform in a recognized domain.

4. Creativity and talent can be developed.

5. Creativity is not a general aptitude, but is dependent on the demands of the domain.

6. Each domain of talent has its own rules and ways in which talent is developed.

7. These rules are well-established and known to experts in the domain. Talent is recognized through certain predictive behaviors. Coaches of athletics know this (body type, dexterity, physicality, etc.). Musicians know this (matching pitch, dexterity, tonal quality of voice, etc.). Each domain has its predictive behaviors that are, for the most part, evident in childhood.

1. The Genetic Aspect

We begin with our genetic heritage. We have certain predispositions, and studies of twins reared apart have indicated that, as we become adults, our genetic heritage becomes more dominant. Our early childhood environment has more importance while we are children than when we are adults. As we age, we become more like our genetic relatives. This layer is beneath the Pyramid, underground.

2. The Emotional Aspect: Personality Attributes

Many studies have emphasized that successful creators in all domains have certain personality attributes in common. These make up the base of the Pyramid, and are the structural weight and support. These are the affective aspects of what a person needs to succeed and they rest on the foundation of genes. Among these are androgyny, creativity, introversion, intuition, naiveté or openness to experience; overexcitabilities, passion for work in a domain, perceptiveness, persistence, preference for complexity, resilience, self-discipline, self-efficacy, and volition, or will.

These attributes were originally from literature review of studies on the talented and creative. I have independently confirmed most of them with my own research on the personalities of talented adolescents.

This list is by no means discrete or complete, but shows that creative adults achieve effectiveness partially by force of personality. Talented adults who achieve success possess many of these attributes. One could call these the foundation, and one could go further and say that some of these may be innate, and some of these (i.e. resilience) can also be developed and directly taught. One is not a prisoner of genetics.

What does it mean to have such personality attributes? What is personality and how does it contribute to effectiveness? Personality is, fortunately or unfortunately, an area in which there are many competing theories. Defined simply as “the set of behavioral or personal characteristics by which an individual is recognizable,” with synonyms such as individuality, selfhood, and identity, personality theory can be psychoanalytic (Ego psychology, object relations, transpersonalism); behavioral or cognitive (quantitative studies using factor analysis or humanistic (using phenomenology, existentialism, gestalt, humanistic, and transpersonal theories). Personality is sometimes equated with character, directing how one lives one’s life. The personality attributes mentioned here have been determined by empirical studies of creative producers—mostly adults, but in some cases, adolescents in special schools and programs. Many of the personality attributes from studies used have focused on the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, based on the Jungian theory of personality. The Cattell 16 Personality Factors Inventory, The Eysenck Personality Inventory, the Gough Creative Personality Inventory, the California Psychological Inventory, the Minnesota Multiphasic Psychological Inventory, and The NEO-PI and others have also been used in studies cited here.

3. The Cognitive Aspect.

Although the cognitive dimension in the form of an IQ score has been over-emphasized, it is certainly essential. IQ is best seen as a minimum criterion, mortar and bricks, with a certain level of intellectual ability necessary for functioning in the world. Having a really high IQ is not necessary for the realization of most talents. Rather, a high enough IQ for college graduation seems to be necessary (except for professional basketball players, actors, and entertainers), and most college graduates have above average IQs but not stratospheric IQs. Domains requiring the highest IQs are philosophy and theoretical physics.

4. The Talent Aspect: Talent in Domains.

The talent itself —inborn, innate, mysterious—should also be developed. It is the tip of the Piirto Pyramid. Each comprehensive high school has experts in most of the talent domains that students will enter. These include mathematics, visual arts, music, theater, sciences, writing and literature, business, entrepreneurship, economics, athletics, dance, the spiritual and theological, philosophy, psychology, the interpersonal, and education. These are all well-defined academically, and if a person has a talent in a domain, he or she can find people who can advise how to enter study in any of them.

When a child can draw so well she is designated the class artist, when an adolescent can throw a ball 85 miles an hour, when a student is accused of cheating on her short story assignment because it sounds so adult, talent is present. Most talents are recognized through certain predictive behaviors, for example voracious reading for linguistically talented students, and preferring to be class treasurer for mathematically talented students. These talents are demonstrated within domains that are socially recognized and valued, and thus may differ from society to society.

An evolutionary thread that is cultural and historical as to which talents are valued at which time needs to be present. For example, hunting talent—acuity of eye combined with a honed instinct for shooting or clubbing and a knowledge of animal habitat—is presently not as socially recognized and valued in western society as is verbal ability—a sensitivity to words and their nuances as expressed through grammatical and idiomatic constructions on paper. In the past, hunting talent was valued much more than verbal talent. Nevertheless, the genetic talent to hunt is still born in certain children, regardless of whether urbanites view such talent as valuable to the society. If the talent for creating computer code was present in children a hundred years ago, would the talent have been needed and rewarded by the society?

5. Environmental “suns”

The four aspects (genetics, personality, intelligence, talent) on this imagistic pyramid could theoretically illustrate the intrapsychic developmental influences on the individual person.

In addition, everyone is influenced by the environment. The environmental influences are shown by the five “suns,” which may be likened to certain factors in the environment. These are the following:

1. The Sun of Home

2. The Sun of Community and Culture

3. The Sun of School

4. The Sun of Gender

5. The Sun of Chance

The three major suns refer to a child’s being (1) in a positive and nurturing home environment, and (2) in a community and culture that conveys values compatible with the educational institution, and that provides support for the home and the school. The (3) school is also a key factor, especially for those children whose other “suns” may have clouds in front of them. Other, smaller suns are (4) the influence of gender, for there have been found few gender differences in personality attributes, in talent, or in intelligence among adult creative producers, thus, gender is an environmental influence; and (5) what chance can provide. The presence or absence of all or several of these make the difference between whether a talent is developed or whether it atrophies.

Unfortunately, it could be said that when a student emerges into adulthood with his or her talent nurtured and developed it is a miracle, because there are so many influences that encroach on talent development. We all know or remember people with outstanding talent who did not or were not able to use or develop that talent because of circumstances such as represented by these suns.

For example, a student whose home life contains trauma such as divorce or poverty may be so involved in that trauma that the talent cannot be emphasized. In the absence of the home’s stability and talent development influence (e.g. lessons, atmosphere for encouragement), the school’s, and the teacher’s or coach’s role becomes to recognize the talent and to encourage lessons, mentors, or special experiences that the parents would otherwise have provided had their situation been better. The “suns” that shine on the pyramid may be hidden by clouds, and in that case, the school plays a key role in the child’s environment.

As another example, in a racist society, the genes that produce one’s race are acted upon environmentally; a person of a certain race may be treated differently in different environments. The school and the community and culture are important in developing or enhancing this genetic inheritance. Retired U. S. general Colin Powell has said that he entered the army because he saw the military as the only community and culture in a racist society where he would be treated fairly, where his genetic inheritance of African American would not be discriminated against, where he could develop his talents fully.

Although many gender differences are genetic and innate, gender’s influence on talent development is also environmental. Boys and girls may be born with equal talent, but something happens along the way. Few personality attributes show significant gender differences [except for Thinking and Feeling on the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) and “tender mindedness” on the 16 Personality Factors Inventory (l6 PF)]. Similarly; few intelligence test scores show significant gender differences (though boys consistently score higher in spatial ability), and so we should look at how the environment influences the development of talent according to gender.

The importance of chance, or luck, cannot be overemphasized. As the principal of a school for children with high IQs in New York City, I received many calls from casting agents and producers wanting to look at our bright children for possible roles in movies, television, and theater. These children had the luck of being born in and living in a center for theatrical activity. I’ll warrant few school principals in, say, Kansas City or Seattle get the weekly and even daily calls I got from casting agents.

The influence of chance comes when a prepared person is in the right place at the right time (as were those children in New York City) or when he or she happens to meet someone who can connect him or her to another person who can help or influence his or her opportunities to interact with the field or domain. The Sun of Chance has clouds over it, for example, when a talented adolescent in a rural high school does not get the counseling needed to make a college choice that will enhance a career. Chance can be improved by manipulating oneself so that one can indeed be in the right place at the right time.

6. The Thorn— Feeling the Call

However, although absolutely necessary, the presence of talent is not sufficient. Many people have talent, and are not interested in doing the work necessary to develop their talents. Emotional investment —MOTIVATION—is the impetus for one acquiring the self-discipline and capturing the passion and commitment to develop the talent. It takes obsession and dedication and energy to chase an idea for years, working on it with a sense of purpose and sacrifice, even in the face of rejection from others. To continue the pursuit of one’s creative obsession requires what is commonly called a vocation or a call. Thus I put an asterisk, or “thorn” on the pyramid to exemplify that talent is not enough for the realization of a life of commitment. Without going into the classical topics of desire, emotion, wisdom, or soul, suffice it to say that the entire picture of talent development ensues when a person is pierced or bothered by a thorn, the daimon, as Carl Jung called it, the acorn, as James Hillman called it, that leads to commitment.

One of the definitions of gift comes from Old French for poison and this is what the talent that bothers may become to a person if the person doesn’t pay attention to it. As well as a joy it is a burden. As well as a pleasure it is a pain. However, the person who possesses the talent also must possess the will and fortitude to pursue the talent down whatever labyrinth it may lead. Jung in Modern Man in Search of a Soul described the creative person, the “poet” (by this he was Platonic and Aristotelian, using the term “poet” to indicate all those who create) and his or her “art” (by this he meant poesis, the work the creative person does) thus: “Art [the creative talent] is a kind of innate drive that seizes a human being and makes him its instrument. The artist [the creator] is not a person endowed with free will who seeks his own ends, but one who allows art to realize its purpose through him” (p. 169). Jung commented that the lives of such creators are often unsatisfactory on the personal level because “a person must pay dearly for the divine gift of the creative fire” (p. 169).

Summary

This model of talent development is, I hope, simple and elegant enough for understanding. The true test of understanding a concept or model is being able to explain the concept to another person. Try it.

As mentioned before, my graduate students in creativity studies classes conduct studies of people whose eminence is enough for scholarly biographies to have been written about them. The framing theory for the studies is this Pyramid.

I have also used this model in my own work—I wrote a book about talent development in creative writers, studying 130 contemporary American writers using this model. It is called “My Teeming Brain”: Understanding Creative Writers, and it was published in 2002 by Hampton Press.

I have also published articles and given speeches using the Piirto Pyramid of Talent Development. Here is what I have found, by domain. See the reference list.

Understanding Creativity In Domains Using The Piirto Pyramid Of Talent Development as A Framework

Domain: Visual Arts

· Genetic Aspect. Does visual arts talent run in families? Perhaps. The families of Calder, Renoir, Wyeth, Picasso, Georgia O’Keeffe, Maurice Utrillo, are examples.

· The Emotional Aspect: Personalities of Visual Artists. The studies have shown that they care little about social conformity, have a high need to achieve success independently, are flexible, and that at IPAR, they scored “pathological” on MMPI. (Barron 1968; Mackinnon, 1978).

· The Cognitive Aspect. The intelligence of visual artists is spatial intelligence (Gardner, 1983), or as Vincent Van Gogh said, “It is at bottom fairly true that a painter as man is too much absorbed by what his eyes see, and is not sufficiently master of the rest of his life.”

· The Domain “Thorn” in Artists. Art is a vocation, a “sacred calling, ” and one who heeds the call has a certain character, besides the interest and the talent. The decision to commit their careers to making art — to being artists — came, “as a progressive or sequential revelation,” according to Getzels and Csikzentmihalyi (1976).

· Sun of Home. Studies have shown no outstanding demographic patterns. As many fathers professionals as blue-collar workers. Families were both encouraging and discouraging (Barron, 1995; Getzels & Csikzentmihalyi, 1976).

· Sun of Community and Culture. Cross-fertilization and cross-cultural influences among artists is common (e.g., Matisse and Picasso). Artists do not create in a vacuum. It is a myth that they don’t respond to community and culture. For example, Picasso’s repeating theme of the Minotaur had a profound influence on Jackson Pollock. Getzels & Csikzentmihalyi (1976) called it a “Loft culture.”

· Sun of School. In school, they showed intense drawing and the emphasis on products, on making the drawings realistic and recognizable representations.

· Sun of Chance. In order to enhance their chances of eminence, they must rent or buy a loft, move to an art center such as NYC, be in a juried art show – try for a one-man/woman show, and/or get an MFA and try to become an art professor.

· Sun of Gender. Women are and have been less likely to become well known visual artists. Women are more likely to go into art education than into fine arts.

Domain: Creative Writers

I wrote a book-length study, “My Teeming Brain”: Understanding Creative Writers (2002). I myself am a creative writer—a published and award-winning poet and novelist. Here is a brief summary of what I found in my study of creative writers.

· Genetic Aspect. Whether or not there is a writing gene is not known. Few writers come from families of writers, but some do: Andre Dubus and his son Andre Dubus II; John Cheever and his son and daughter Ben and Susan. Screenwriters and novelists Nora and Delia Ephron are the daughters of Hollywood screenwriters.

· The Emotional Aspect: Personalities of Creative Writers. 1. Independence/ nonconformity; 2. Drive/ resiliency; 3. Courage/ risk-taking; 4. Androgyny; 6. Introversion 7. Intensity or OEs; 8. Naiveté or an attitude of openness; 9. Intuitive (N) and perceptive (P); 10. Energy transmitted into productivity through self-discipline; 11. Ambition /envy; 12. Concern with philosophical matters; 13. Frankness often expressed in political or social activism; 14. Psychopathology; 15. Depression; 16. Empathy; 17. A sense of humor (most humorists are first writers).

· The Cognitive Aspect: Intelligence of Creative Writers. Writers usually score very high on verbal intelligence sections of the IQ tests, and not so high on spatial and mathematical. The IPAR studies showed that creative writers scored 156 on the Terman Concept Mastery Test. Compare this to the average of 137 for gifted subjects.

· The Domain Thorn in Creative Writers: Why write? Because one can’t not write. The writing is not for fame, money, or notoriety, but to fulfill a more personal need, the need to find out what one is thinking, the need to put it down so that it can be dealt with, the need to codify emotion.

The Environmental Suns have been reduced to sixteen themes, as follows:

· Sun of Home

1: Predictive behavior of extensive early reading.

2: Predictive behavior of early publication and interest in writing.

3: Unconventional families and family traumas (e.g.: parental alcoholism, moving often, death of a parent, uncertain finances). This includes the search for the father, as in writing families, the fathers are often viewed as weak or ineffectual. Playwright Arthur Miller (1987), said, “it would strike me years later how many male writers had fathers who had actually failed or whom the sons had perceived as failures.” He listed William Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Wolfe, Edgar Allan Poe, John Steinbeck, Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, Anton Chekhov, Nathaniel Hawthorne, August Strindberg, and Fyodor Dostoevsky. “The list is too long to consign the phenomenon to idiosyncratic accident” (p. 34).

4. Incidence of depression and/or acts such as use of alcohol, drugs, or the like.

5. Being in an occupation different from their parents.

· Sun of Community and Culture

6: Feeling of marginalization or being an outsider, and a resulting need to have their group’s story told.

7: Late career recognition.

· Sun of School

8: High academic achievement and many writing awards.

9: Nurturing of talents by both male and female teachers and mentors.

10. Attendance at prestigious colleges, majoring in English literature, but without attaining the Ph.D.

· Sun of Chance

11: Residence in New York City at some point, especially among the most prominent.

12: The accident of place of birth and of ethnicity forms the subject matter.

· Sun of Gender

13: The classic double bind of women is present in creative women writers as well: Conflict with combining parenthood and careers in writing. “Everything around you and much of what’s inside you is screaming that what your child needs is more important than what you need because you’re a MOTHER now and MOTHERS give up things for their children, up to and including everything, even their own lives. If I did not write, I would be a terrible vengeful mother.” (Durban, 1991, p. 8)

14: Societal gender expectations incongruent with their essential personalities.

15: History of divorce more prevalent in women.

16: Military service more prevalent in men.

Domain: Scientists and Mathematicians

1. The Genetic Aspect: There is some evidence of heritability in families of scientists. For example, take The Darwins – Erasmus, Sir George Howard, Francis Galton, Sir Francis Darwin, Dir Horace Darwin, George Galton Darwin, Josiah Wedgewood, Thomas Wedgewood and the Huxleys – Sir Andrew Fielding Huxley who won the Nobel Prize, Sir Julian Huxley, biologist, and Aldous Huxley, a novelist who wrote science fiction (Brave New World)

2. The Emotional Aspect: Personalities of Scientists and Mathematicians: Creative scientists had personalities similar to artists and writers had personalities, except that the scientists had more emotional stability than the artists and writers. (Cattell, Cattell, and Johns, 1984; Cattell, Eber, & Tatuoka, 1970).

3. The Cognitive Aspect: Intelligence of Scientists and Mathematicians. According to Gardner (1983), scientists and mathematicians have Logical-mathematical intelligence and Spatial intelligence. More generally, they receive high scores in mathematics and in spatial ability on IQ tests. What is the difference between scientists and mathematicians? Scientists use mathematics as a tool. Mathematicians find joy and fulfillment in the beauty of mathematics for its own sake, or the elegance of the proof. Scientists find joy and fulfillment in considering the true nature of physical reality. Scientists want to unlock the secrets of nature, and they are motivated by their beliefs in underlying universal themes or patterns in nature. They often publish their work with mathematicians (e.g., Einstein called upon the mathematician Ernst Strauss while he was at Princeton).

4. The Domain Thorn: Passion for Science and Mathematics. Biographical studies show they have passion and persistence for doing the work. As children, scientists incorporate their science interest into their play with collections of rocks, insects, spiders and the like. Young mathematicians like numbers; for example, they may read telephone books.

5. Sun of Home. They come from more stable homes than other creators, especially writers and actors. The father presence as an influential force. Firstborns and only children make up more than half of active scientists (Simonton, 1999).

6. Sun of School. Scientists and Mathematicians often skip grades, and take the most challenging courses. They list their favorite courses as mathematics and science.

7. Sun of Community and Culture. The Outsider phenomenon, or Marginality (Simonton, 1986) may apply to this domain. Many scientists come from immigrant populations, especially Jewish background

8. Sun of Chance. The phenomenon of serendipity often applies. Serendipity can take place when a person has tried and tried to solve a problem but has failed until a universal characteristic becomes apparent; when a chance discovery truly happens; when an unanticipated find occurs; when an entirely different problem is solved; or when someone is tinkering and just seeing what happens.

9. Sun of Gender: As Simonton (1999) said, “In the annals of science, fewer than 1% of all notables are female. Names like Hypatia, Caroline Herschel, Marie Curie, and Barbara McClintock are but drops in a sea of male scientists” (p. 256).

Domain: Inventors

· Emotional Aspect: Personalities of Inventors. They demonstrate the core attitude of Naiveté, and the ability to focus quickly. They show high self-confidence and high self-esteem. They also demonstrate the core attitude of Risk-taking, a willingness to troubleshoot and to plunge in.

· Cognitive Aspect: Inventors. They demonstrate Spatial (figural) intelligence By the way, most job titles in the U.S. government’s directory require figural intelligence as opposed to semantic (linguistic) or symbolic intelligence.

· Sun of Community and Culture. Inventors Hall of Fame inductees since the 1960s have been what MacKinnon (1978) called Captive inventors, those hired by a university or a company. A Ph.D. is common (physics, biochemistry, ceramics, chemistry, engineering).

· Sun of Gender. Inventors inducted into the Inventors Hall of Fame in Akron, Ohio, have been overwhelmingly male. They hold many patents, not just the ones for the invention for which they were inducted.

Domain: Entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurs such as J. Paul Getty, Bill Gates, and Warren Buffett came from rich or very comfortable families; they had access to expert advice and legal protection of their ideas; they were readers and thinkers; they were smart in mathematics (e.g., Bill Gates scored 800 on his SAT); and they liked money from an early age.

Domain: Musicians, Composers, Conductors

· The Genetic Aspect. We don’t know whether there is a music gene or music genes, but music talent does seem to run in families, e.g., the Mozart family, the Mendelssohn, the Bachs, the Dylans (Bob and his son Jakob) and the Simons (Paul and his son Harper).

· The Emotional Aspect: Personality attributes. Studies with the 16 PF by Kemp (1996) have shown that male composers are aloof, dominant, sensitive, controlled, imaginative and self-sufficient, while female professional composers dominant and self-sufficient. Composers were the most extreme in all the personality factors. Other and various studies of rock musicians have shown them to have High Neuroticism and Openness, Low Agreeableness and Conscientiousness, High Excitement-Seeking and Positive Emotions, Low Trust, Straightforwardness, and Compliance, Low Conscientiousness, and Average Achievement Striving (Gillespie and Myors, 2000).

· The Cognitive Aspect: Musical intelligence. Appears early in spontaneous singing, chanting, creating sounds with instruments, imitating songs, remembering songs heard, interest in playing (Haroutounian, 2002).

· Talent in the Domain: The Thorn. Music is the expression of deep emotion. Conductor Herbert Blomstedt said, “After a concert I feel exhilarated and want to do it again. I never get tired of making music.” Conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen said, “Sometimes I have these funny moments of joy. I’m studying the score and I suddenly realize how great the music is, and I’m overcome by very powerful feelings of euphoria.”

· The Sun of Home. The family of the musical talent most often has a keyboard instrument. The families are amateur musicians who perform music at home as pleasure, and who listen to music together. They also attend concerts of other musicians. The Sun of Home in rock and popular musicians is less stable, less supportive in terms of lessons, less tolerant of practice, and less full of encouragement. Resilience is the key personality attribute. Rock musicians experienced “Unhappy childhoods, painful addictions (to sex or drugs), fears of inadequacies and abuses both endured and inflicted are common themes, sometimes to the point of numbing repetition.”

· Sun of School. One must audition and constantly practice, and take lessons from ever more advanced teachers. The master teachers expected discipline and commitment. Being a student of a master teacher means more than just taking lessons; it means adopting a style, a sense of musical repertoire, and a rising in standards of musicianship and performance.

· The Sun of Community and Culture. As in other domains, the importance of hanging around with other musicians and artists cannot be underestimated. I call this the “Salon Effect. ”

· The Sun of Chance. The talented musicians, as in other domains, must be ready for chance to strike. For example, take the stories of Leonard Bernstein and of Esa-Pekka Salonen. Both were assistant conductors who got their big chance when the maestros under whom they worked had to miss a concert. This is the “understudy effect.”

· The Sun of Gender. “Lookism” is alive and well in the music domain. Ella Fitzgerald was called too ugly to front a band. Janis Joplin was voted Ugliest Man on Campus. Anne Sophie Mutter is known for her sexy album covers, as is Lara St. John, so much so, that the women bemoan ever being taken seriously as classical musicians. Mama Cass almost didn’t make the Mamas and Papas because she was overweight.

Physical Performers: Actors, Dancers, and Athletes

· Actors: The Genetic Aspect. Families of actors exist, and have existed for ages. Take, for example, the Bernhardts, Barrymores, Booths, Sheens, Fondas, Redgraves, and Houstons.

· Actors: The Emotional Aspect: Personality Attributes. Psychometric studies have shown the preference for ENFJ (Extraversion, Intuition, Feeling, and Judgment), for resilience, and a tolerance of ambiguity.

· Actors, Dancers, Athletes: The Intelligences: Cognitive aspect. These physical performers show what Gardner (1983) called bodily-kinesthetic intelligence, interpersonal intelligence, and intrapersonal intelligence

· Passion for the Domain: The Thorn. As in other domains, the passion must drive the performance. As Laura Linley said, “It’s true what they say. You have to love the work; you have to love acting more than you love success. Or it can really damage you.’‘

· Sun of Home in Actors. The biographies show family turmoil and/or Bohemian families, for example, the Phoenixes, the Downeys, the Fiennes. Poverty was also present in many theatrical families.

· Sun of School: Actors. Actors have a large dropout rate, mostly from university, some just short of graduating, like Brad Pitt and Steve Martin. They are practical, and want to learn the craft, not the liberal arts. Even though, in the U.S., more than 80 master’s degree programs, 300-plus bachelor’s degree programs, and several hundred non-degree conservatory programs, many actors do not finish school.

· The Sun of Chance: The look. Unfortunately, in the theater, talent is preceded by looks, at least in the United States. “Getting a good head shot is as important as studying with the best teacher,” said a theater artist I interviewed. The best singers and dancers, not the best actors get roles in musical theater.

· The Sun of Chance. “Good genes,” said Jane Fonda, when she confessed she no longer exercises very much. Sophia Loren’s chest got the attention of Carlo Ponti, and the rest is history. Ava Gardner’s looks got her her first jobs. Family connections also matter.

· The Sun of Gender. The issue of women having to be thin and beautiful and young in order to be performers is present, to a greater extent than for men, though it is present there as well. “Let’s hear it for the fat girls!” shouted Camryn Manheim when she won an Emmy. However, she and only a few others such as Kathy Bates are permitted to be overweight.

Domain: Dancers and Athletes

· Personality Attributes: The Emotional Aspect in Dancers and Athletes. Personality studies of dancers and athletes have shown that they have the ability to cope with and control anxiety, Confidence, Mental toughness/resiliency, sport intelligence, ability to focus and block distractions, competitiveness, hard work ethics, coachability, and high levels of hope.

· Domain Thorn – Athletes. “Baseball drove me. It pushed me. ” said Derek Jeter in his autobiography. “I was in love with basketball. I couldn’t wait for school to be over so I could run right over to the Stadium, ” said Hakeem Olajuwon in his.

· Sun of Home: Dancers and Athletes. These creative performers had parents who were willing to pay for lessons and the intense training necessary. They also may have felt the necessity to move the whole family in order to find the perfect coach (as in tennis, ice skating, and gymnastics). Even choreographer Alvin Ailey’s mother, in poverty-stricken Texas, encouraged him to move to Los Angeles to pursue his interests. Male dancers often experience the disapproval of their fathers of their choice of dance.

· Sun of School. Aspiring athletes attend sports camps, special schools for various sports. Hour after hour are spent shooting hoops, keeping a soccer ball in the air, practicing plays and moves. They practice, practice, practice to the point of automaticity

· Sun of Community and Culture. The importance of the ensemble, the team, and the group is key in this domain. No one achieves on his own without help from the group. These groups have initiations, rituals, and exclusionary practices.

· Sun of Chance. Again, the “luck” of having the right physical makeup for the dance or sport cannot be underestimated. Dance and each sport have its physical requirements.

· Sun of Gender. The personality attribute of androgyny in athletes at the top levels has been studied. Male and female athletes at elite levels (on national teams) are remarkably similar in personality. They have high achievement motivation, high tolerance for pain, are highly competitive, and are able to train with great intensity.

These, briefly, have been a few examples from several domains of talent, organized according to the framework of the Piirto Pyramid of Talent Development.

References

Adler, M. (1952). The great ideas: A syntopticon of Great Books of the Western World. Chicago, IL: The Encyclopedia Britannica.

Baird, L. (1985). Do grades and tests predict adult accomplishment? Research in Higher Education, 23(1) 3-85.

Barron, F. (1968). Creativity and personal freedom. New York: Van Nostrand.

Barron, F. (1995). No rootless flower: An ecology of creativity. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Benbow, C. P. (1992). Mathematical talent: Its nature and consequences. In N. Colangelo, S. G. Assouline, and D. L. Ambroson, Eds. Talent development: Proceedings from the 1991 Henry B. and Jocelyn Wallace National Research Symposium on Talent Development, pp. 95-123. Unionville, NY: Trillium Press.

Block, J., & Kremen, A.M. (1996). IQ and ego resiliency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70 (2), 346-361.

Cattell, R., Cattell, M.D., & Johns, E.F. (1984). Handbook for the High School Personality Questionnaire (HSPQ). Champaign, IL: Institute for Personality and Ability Testing.

Cattell, R., Eber, H.W., & Tatsuoka, M.M. (1970). Handbook for the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire. Champaign, IL: Institute for Personality and Ability Testing.

Corno, L., and Kanfer, R. (1993). The role of volition in learning and performance. In L. Darling-Hammond, Ed. Review of research in education, 19, pp. 301-342. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow. New York: Cambridge.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., Rathunde, K., and Whalen, S. (1993). Talented teenagers: The roots of success and failure. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dabrowski, K. (1964). Positive disintegration. Boston: Little, Brown.

Davidson, J. E. (1992). Insights about giftedness: The role of problem solving abilities. In N. Colangelo, S. G. Assouline, and D. L. Ambroson, Eds. Talent development: Proceedings from the 1991 Henry B. and Jocelyn Wallace National Research Symposium on Talent Development pp. 125-142. Unionville, NY: Trillium Press.

Dewey, J. (1934). Art and experience. New York: Putnam.

Durban, P. (1991). Layers. In E. Shelnutt (Ed.), The confidence woman: 26 female writers at work (pp. 7-26). Marietta, GA: Longstreet.

Eysenck, H. J. (1993). Creativity and personality: Suggestions for a theory. Psychological Inquiry, 4, 147-78

Feldman, D. H. (1982). A developmental framework for research with gifted children. In D. Feldman (Ed.), New directions for child development: Developmental approaches to giftedness and creativity, 17, (pp. 31-46). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Feist, G. H. (1999). Influence of personality on artistic and scientific creativity. In R. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 273-296. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Freeman, J. (Ed). (1986). The psychology of gifted children: Perspectives on development and education. New York: Wiley.

Freeman, J. (2001) Mentoring gifted pupils. Educating Able Children, 5, 6-12.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind. New York: Basic.

Getzels, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1976). The creative vision: A longitudinal study of problem finding in art. New York: Wiley.

Gillespie, W., & Myors, B. (2000). Personality of rock musicians. Psychology of Music, 28(2), 154-165.

Ghiselin, B. (1952). The creative process. New York: Bantam.

Haroutounian, J. (2002). Kindling the spark: Recognizing and developing musical talent. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hillman, J. (1996). The soul’s code: In search of character and calling. New York: Random House.

Jenkins-Friedman, R. (1992). Zorba’s conundrum: Evaluative aspect of self-concept in talented individuals. Quest, 3(1): 1-7.

Jeter, D (With Curry, J). (2000). The life you imagine: Life lessons for achieving your dreams. New York: Crown Publishers.

Jung, C. G. (1933). Modern man in search of a soul. New York: Random House.

Jung, C. G. (1965). Memories, dreams, reflections. New York: Vintage.

Langer, S. K. (1957). Problems of art. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Kaufman, J., & Baer, J. (Eds.). (2004). Creativity in domains: Faces of the muse. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kaufman, J., & Kaufman, S. (Eds.). (2011.) The psychology of creative writing. Cambridge University Press.

Kemp, A. E. (1996). The musical temperament: Psychology and personality of musicians. New York: Oxford University Press.

MacKinnon, D. (1975). IPAR’s contribution to the conceptualization and study of creativity. In I.A. Taylor and J.W. Getzels (Eds.), Perspectives in creativity (pp. 60-89). Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company.

MacKinnon, D. (1978). In search of human effectiveness: Identifying and developing creativity. Buffalo, NY: Bearly Limited.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1999). A five-factor theory of personality. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds)., Handbook of personality theory and research, 2nd Ed. (Pp. 139-153). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Myers, I. B., and McCaulley, M. H. (1985). Manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Piechowski, M. M. (1979). Developmental potential. In N. Colangelo and R.T. Zaffrann, Eds. New voices in counseling the gifted, pp. 25-57. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.

Piirto, J. (1992/1998). Understanding those who create. Tempe, AZ: Gifted Psychology Press.

Piirto, J. (1994/1999). Talented children and adults: Their development and education. New York: Macmillan.

Piirto, J. (1995a). Deeper and broader: The pyramid of talent development in the context of the giftedness construct. In M. W. Katzko and F. J. Mönks (Eds.), Nurturing talent: Individual needs and social ability (pp. 10-20). Proceedings of the Fourth Conference of the European Council for High Ability. The Netherlands: Van Gorcum, Assen.

Piirto, J. (1995b). Deeper and broader: The Pyramid of Talent Development in the context of the giftedness construct. Educational Forum, 59, 364-369.

Piirto, J. (1998). Understanding those who create. 2nd Edition. Scottsdale, AZ: Gifted Psychology Press.

Piirto, J. (2000a). The Pyramid of Talent Development. Gifted Child Today, 23(6), 22-29.

Piirto J. (2000b). How parents and teachers can enhance creativity in children. In M.D. Gold & C. R. Harris (Eds.), Fostering creativity in children, K-8: Theory and practice (pp. 49-68). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Piirto, J. (2002) “My teeming brain: Understanding creative writers. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Piirto, J. (2004). Understanding creativity. Scottsdale, AZ: Great Potential Press.

Piirto J. (2005a). The creative process in poets. In J. Kaufman and J. Baer (Eds.). Creativity in domains: Faces of the muse (pp. 1-21). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Piirto J. (2005b) Rethinking the creativity curriculum. Gifted Education Communicator, 36 (2), 12-19. Journal of the California Association for the Gifted.

Piirto, J. (2007a). Talented children and adults: Their development and education, 3rd ed. Waco TX: Prufrock Press.

Piirto J. (2007b). Understanding visual artists and creative writers. In K. Tirri (Ed.), Values and foundations in gifted education (pp. 34-48). Pieterlen, Switzerland: Peter Lang International.

Piirto J. (2007c). A postmodern view of the creative process. In J. Kincheloe and R. Horn (Eds.), Educational Psychology Handbook. Greenwood Press.

Piirto J. (2008a). Understanding creativity in domains using the Piirto Pyramid of Talent Development as a framework. Mensa Research Journal, 39(1), 74-84.

Piirto J. (2008b). Giftedness in nonacademic domains. In S. Pfeiffer (Ed.), Handbook of giftedness in children: Psych-educational theory, research, and best practices (pp. 367-386). New York: Springer.

Piirto J. (2008c). Rethinking the creativity curriculum: An organic approach to creativity enhancement. Mensa Research Journal, 39(1), 85-94.

Piirto J. (2008f). Rethinking the creativity curriculum: An organic approach to creativity enhancement. Mensa Research Journal, 39(1), 85-94.

Piirto J. (2008g). Saunas: Poetry by Jane Piirto. Bay City, MI: Mayapple Press.

Piirto J. (2009a). Eminence and creativity in selected visual artists. In (Eds.) Leading Change in Gifted Education: The Festschrift of Dr. Joyce VanTassel-Baska (pp. 13-26). Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Piirto J. (2009b). Personalities of creative writers. In S. Kaufman & J. Kaufman (Eds.), Psychology of Creative Writing. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Piirto J. (2009c). Eminent women. In Encyclopedia of giftedness, creativity, and talent. (Ed. B. Kerr). Academic Press.

Piirto J. (2009d). The creative process as creators practice it: A view of creativity with emphasis on what creators really do. In B. Cramond, N. L. Hafenstein, & K. Haines, Perspectives in gifted education: Creativity Monograph (pp. 42-68). University of Denver.

Piirto, J. (2010a). Giftedness in non-academic domains. In S. Pfeiffer (Ed.), Handbook of the gifted and talented: A psychological approach. New York: Springer.

Piirto J. (2010b). The five core attitudes and seven I’s of creativity. In J. Kaufman and R. Beghetto (Eds.), Nurturing creativity in the classroom. New York: Cambridge.

Piirto, J. (2011a). The personalities of creative writers. In J. Kaufman and S. Kaufman (Eds.). The psychology of creative writing. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Piirto J. (2011b). Entry, Synchronicity. In M. Runco and S. Pritzker (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Creativity, 2nd Ed. London: Elsevier/Academic Press Publications.

Piirto J. (2011c). Themes in the lives of creative writers. In E. Grigorenko, E. Mambrino, & D. Preiss (Eds.), Handbook of Writing. New York: Psychology Press.

Piirto, J., & Fraas, J. (In press). A Mixed-Methods Comparison Of Vocational And Identified Gifted High School Students On The Overexcitability Questionnaire (OEQ). Journal for the Education of the Gifted.

Piirto, J., and Fraas, J. (1995). Androgyny in the personalities of talented adolescents. Journal for Secondary Gifted Education,1, 93-102.

Piirto J., & Johnson, G. (2004). Personality attributes of talented adolescents. Paper presented at the National Association for Gifted Children conference, Salt Lake City, UT; at the Wallace Research Symposium, in Iowa City, IA; and at the European Council for High Ability conference, Pamplona, Spain.

Piirto J., Montgomery, D., & May, J. (2008). A comparison of Ohio and Korean high school talented youth on the OEQ II. High Ability Studies19, 141-153.

Piirto J., Montgomery D., & Thurman, J. (2009, November). Personality and perfectionism. Paper presented at National Association for Gifted Children Conference, St. Louis, MO.

Plato, The Ion. In Great Books of the Western World, Vol. 7. (1952) Chicago, IL: Encyclopedia Britannica.

Renzulli, J. (1978). What makes giftedness? Reexamining a definition. Phi Delta Kappan, 60: 180-184, 261.

Reynolds, F. C., & Piirto, J. (2005). Depth psychology and giftedness. Finding the soul in gifted education. Roeper Review, 27(3). 164-171.

Reynolds, F. C., & Piirto, J. (2007). Honoring and suffering the “thorn”: Marking, naming, and eldering. Roeper Review, 29(2).

Reynolds, F. C., & Piirto, J. (2009). Depth psychology and integrity. In T. Cross and D. Ambrose (Eds.). Morality, Ethics, and Gifted Minds (pp. 195-206). New York: Springer Science.

Richards, R. (1999). Four Ps of creativity. In M. Runco and S. Pritzker (Eds.), Encyclopedia of creativity, Vol. I (pp. 733-742). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Runco, M., & Pritzker, S. (Eds.). (1999). Encyclopedia of creativity (2 vols). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Santayana, G. (1896). The sense of beauty: Being the outline of aesthetic theory. New York: Dover Publications.

Silverman, L. K., (Ed). (1993). Counseling the gifted and talented. Denver, CO: Love.

Simonton, D. K. (1986). Biographical typicality, eminence and achievement styles. Journal of Creative Behavior, 20 (1), 17-18.

Simonton, D. K. (1988). Scientific genius. New York: Harvard University Press.

Simonton, D. K. (1994). Greatness: Who makes history and why. New York: Guilford.

Sternberg, R., and Davidson, J. (1985). Cognitive development in the gifted and talented. In F. Horowitz and F. O’Brien.(Eds.), The gifted and talented: A developmental perspective, pp. 37-74. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Sternberg, R., and Lubart, T. I. (1991). An investment theory of creativity and its development. Human Development, 34: 1-31.

Tannenbaum, A. (1983). Gifted children. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Macmillan.

Torrance, E. P. (1987). Teaching for creativity. In S. Isaksen (Ed.), Frontiers of creativity research: Beyond the basics, pp. 190-215. Buffalo, NY: Bearly Ltd.

Zimmerman, B. J., Bandura, A., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1992). Self-motivation for academic attainment: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. American Educational Research Journal, 29, 663-676.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jane Piirto

WEBSITE:

or just Google me.

Other Books By Jane Piirto

The Three-Week Trance Diet (novel) also ebook

A Location in the Upper Peninsula: Collected Poems, Stories, Essays (also ebook)

Understanding Those Who Create (scholarly nonfiction, 2 editions)

Understanding Creativity (scholarly nonfiction)

Talented Children and Adults (textbook, 3 editions)

“My Teeming Brain”: Understanding Creative Writers (scholarly nonfiction—psychology)

Creativity for 21st Century Skills: How to Embed Creativity Into the Curriculum

Organic Creativity in the Classroom: Teaching to Intuition in Academics and the Arts

(scholarly nonfiction—education)

Saunas (poetry)

Mamamama (poetry)

Postcards from the Upper Peninsula (poetry)

Between the Memory and the Experience (poetry)

Silent Midnight Snow Comes Down (poetry)

Young Mather in Ishpeming (creative nonfiction) (also ebook)

Journeys to Sacred Places (poetry)

Luovuus (scholarly nonfiction)

Sleeping With Strangers (poetry)

Labyrinth (novella)–ebook

The Arrest (novel)–ebook

Guidance and Counseling of Gifted and Talented Adolescents–ebook