Why Does A Writer Write? Because.

© Jane Piirto. All Rights Reserved

Why does a person write poems when there’s nobody out there to read them? I subscribe to several literary journals where poetry is published, and have a large collection of poetry books by contemporary writers, but I guess I’m unusual. Yet I’ll wager there are few people who haven’t been moved to write a poem to a love, in the throes of emotion, anger, sorrow. I asked a graduate class how many people read poetry for pleasure, and of the thirty teachers there, many of them English teachers, only two admitted to it. I know that when the poets on our campus give our annual reading, only a few people come unless the professors have assigned the students.

I like to go to poetry readings because they remind me of worship. The air is filled with considered words, and when the artist, the fiction writer, essay writer, or poet, can savor and can express out loud in a dramatic fashion, these wordsnaturally, the writer has to be able to performI leave the reading with a feeling of spiritual awe. Perhaps the hard work required of the listener at such events is the reason people don’t buy, read, or attend to poetry.

For me, who has been writing poems for many years now, poetry is a natural means of expression. By this time, I know when an incident happens, that I will write a poem about it. I get an indefinable feeling of edginess, anxiety, that is only assuaged when I write the poem. I work with pen in my journal, or on my computer, in line form. The fun of writing a poem is revising and revising, thinking, trying out, reading it out loud, singing it in rhythm, seeing whether it fits some urgent mental format that seems to arise through the writing. Writing poetry is an exercise in specificity. Finding just the right word, trying it out, counting its syllables, checking on its connotations, or seeing where it will lead the meaning, all provides great pleasure to me.

I really don’t write for the reader because I know I have few readers and will probably always have few readers. I write and revise as a form of seeing clearly and saying well.

I am in a state of elation as I sit thinking, or drive around, mentally trying out different words, running back and forth to the word processor to print out just one more version to see whether this one works.

It may take years to get it so I don’t want to revise it anymore.

Such a private, personal passion playing with poetry is! No chance of fame or fortune. The elite art, some people call it. Some of my poems have been inspired by various events. I’ve recently written an essay, “My Writing Life,” where I tried to explore the roots of my own creativity, in response to what I found about creators in my 1992 book, Understanding Those Who Create, and in my 1994 book, Talented Children and Adults. Here is an excerpt from the book, A Location in the Upper Peninsula, from the essay, “My Writing Life.”

My childhood in Ishpeming, Michigan, was spent reading and playing in our woods and minepit-filled neighborhood, Cleveland Location. I remember my father and mother talking about buying my Uncle Art’s house when he moved to California. This house was across town on Empire Street, near the city playground. The house had a small rocky bluff in the back yard. I cried and carried on at the thought of moving so far (about 1-1/2 miles). I couldn’t imagine living in such a citified neighborhood, with just that small bluff, even if it was near the playground and the ice rink and the football field and tennis courts.

My parents didn’t buy Uncle Art’s house across town. We have never been sorry. My mother still lives in Cleveland Location. I go home there several times a year, and walk in those woods, climb those rocks, and sit on top of Jasper Knob. The concept of “place” is very important to my creativity, and much of my writing is inspired by the various places I have visited and lived in. The very land itself inspires me.

In my research on creativity and creative people for the books and articles I’ve written and for the speeches I give, adult creativity is often shown to be shaped by free imaginative play during childhood. Many inventors, for example, come from rural backgrounds. Being able to play freely, without the invading eyes of adults was a gift of our neighborhood to us.

My own tomboy life was also shaped by the reading, the constant, ceaseless, compulsive, careless reading. When I wasn’t playing outside, I was reading.

My mother has a sketch of me in my braids, reading Bill Cody: Hero of the West. I hated to pose for her so I would read during that boring hour when she would sketch us.

The artistic mother with an attitude toward books, art, and life that was unconventional and different from anybody else’s mother, is also common in biographies of creative people, especially writers. Our mother produced two writers and one artist (not to count her grandson, my son, Steven, a professional photographer and visual artist): my sister Rebecca has written two books and is a practicing journalist. My sister Ruth is a weaver who sells her finely wrought craft work and whose handmade Christmas and birthday gifts are to die for.

But I was and am, the reader. I read four, five, sometimes six books a week, all from the Carnegie Public Library on Main Street. I still go there for books every time I come to town, and I belong to the Friends of the Library, devouring their semi-annual newsletter sent to me in Ohio, where I live. I read my way through the children’s room where I can still recall the precise spots where the Bobbsey Twin books and the Cherry Ames Student Nurse books were on the shelves. Miss Dunden, the kind librarian with the wooden hand, let me go upstairs to the teenage section and then to the adult section, in fifth and sixth grade.

Our parents didn’t buy books for us; my mother said that was a waste of money when we could find anything we wanted in the library, and for free. The librarians wouldn’t even charge much for overdue books for us readers. Now I am in temporary despair whenever I finish one book and haven’t found the next one. To prevent that, I always have several books going. My latest favorite reading is biography.

I got decent enough grades, and in junior high was put in what we called the “A” class. Our English teacher, Mrs. Fritz, brought back for several of us, small red Austrian flags from her summer home in Salzburg, Austria, as a reward for learning to diagram sentences the fastest.

My verbal interests also extended to the theatrical or oratorical, for I remember our scary principal, Mr. Ikola, inviting my friend Carolyn and me to give our declamations down at the high school, for an assembly in front of the high school kids. Mine was “The Old Woman and the Clock,” where I shouted “Ti-i-ick tock, Ti-i-ick tock” in a very dramatic fashion.

Both Carolyn and I have done a lot of public speaking, so maybe those early declamations were helpful.

Being a good Finnish-American girl, doing everything expected of me, my class standing and membership in the National Honor Society was acceptable but not outstanding. There was no hint that I would take up writing, except for my constant reading. I didn’t write anything for personal pleasure or expression, except letters. I had several aborted attempts at keeping a diary. Years later, I heard that our high school English teacher, Mr. Renz, had invited some other kids to join a summer writing group. I wasn’t invited to participate, so he probably viewed me as not having enough writing talent for such enrichment. Maybe he’d be surprised that I’m the one who turned out to be the writer. We had to memorize a lot of poetry in his class, and I am very grateful.

I can still remember sitting in the alto section just after lunch in mixed chorus, memorizing poetry for the quiz in his class next hour. Those words he had us remember are still in my brain. Teachers are reluctant to ask students to memorize nowadays.

Another childhood influence was the movies. Oh I loved the movies. My friends and I would go to the double features on Saturday afternoons for $.12 plus $.05 for popcorn. There would be two black and white movies, cowboy films, and then a serial. Each serial had twelve episodes. There were newsreels and preview of coming attractions beforehand. Each movie was also preceded by a cartoon. I would act out these movies in fantasy play on the bluff across from our house, and would spend days thinking about the plots. My mother and father had to make a rule I only could attend one movie a week, just as they had to make a rule that I couldn’t read at the table.

We were good Lutheran Christian kids, and got “saved” by Jesus during the summers in high school. Every summer we in Luther League would go to Bible Camp and during that week we would get saved, declare Jesus as our personal savior. Every fall we would “fall away,” to worldly pursuits such as the dances at the Youth Center and later at the high school gymnasium. We would dance with the girls to the fast numbers, booming loud Elvis Presley and Gene Vincent. Then, when a slow dance would come on, The Platters or Pat Boone, we would retreat to the sides of the room and hope a boy would ask us to dance. At Bible Camp those fundamentalist Lutheran evangelists would preach hell and damnation to us vulnerable teenagers and scare us–for a little while, a few weeks, a few months.

But one year it really took, that salvation. We were determined not to fall away. It was the summer before our senior year in high school. We came back and put away our tubes of lipstick, our pancake makeup, our perfume. We carried our Bibles wherever we went so if we got a chance to witness, we would.

One of my best friends was elected to the Homecoming court that fall, and rather than go to the dance, she and her date and me and mine, who was on the football team, left after the award ceremonies and drove in her date’s Volkswagen, in our formal gowns, to the Coffee Cup in Marquette to have coffee and not be tempted with evil rock and roll and darkened rooms for dancing.

Again, in the studies of writers I have read, there was often a spiritual search and conversion during adolescence, and so I am not unusual here, either. However, like those other writers, the salvation didn’t “take” with me.

Friends and I carried on fervent correspondence, writing Christian epistles to each other, deconstructing verses of the Bible from our daily devotions, doing literary criticism before we knew there was such a thing. Recently, one of those friends and I sat down and she read her letters to me that my mother had stored in her attic and had recently returned to me. We looked them over and recognized our searching teenaged selves.

The letters that went back and forth between friends in the late 1950s and early 1960s were detailed, honest, and probing, quite confessional, and above all, indicated the mental curiosity of our young minds. Too bad the art of letter writing has been subsumed to the telephone, though with e-mail in cyberspace, there’s some hope.

Being a child of the working class, and the oldest child, I was the first in my family to go to college, though in the Piirto family it was expected that all grandchildren would go. Almost all my 35 first cousins have further education beyond high school. I chose my college without counseling or aid. I don’t even know if our high school had a counselor, and I missed the testing for the SAT, for some reason or another. I wanted to attend Suomi College in Hancock, Michigan, a Lutheran College of Finnish origins.

My year at Suomi College was not academically challenging, except for a course from Professor Saarinen called, one semester, “Christian Doctrine,” and the other, “Christian Ethics.” I had no idea what he was talking about and I loved it. My mind was strained and stretching. I started to read the existentialists and remember struggling through Martin Buber’s I and Thou, Kierkegaard’s leap of faith works, Sartre’s No Exit, and Camus’ The Plague. I was an honor student and elected to a dramatic society.

At Suomi, even though it was a Christian college, my reading of these dense texts and those wild drinking guys from Michigan Tech, across the Portage Canal in Houghton, caused me to fall away again. The Suomi College Choir went on a tour to the east that year, and when we Finnish American rural girls saw how short the skirts were in New York City, we rolled up our waistbands and put on more red lipstick. I remember the Staten Island Ferry and the old Finnish church in a rundown neighborhood in Brooklyn. I remember the bus driving out of New York City and me looking out the windows vowing, “I’m coming back to you someday, big city.” And I did, twenty-three years later.

Like most young girls, I wrote my few boyfriends letters and love poems with carefully chosen lyrics. I would write and rewrite these letters, trying to be cool and say it right and not tell him out loud how much I missed him. The right words were very important. One had to be cool yet ardent. Erotic love is a great impetus for poetry. Emotion rules and there are few people who haven’t scrawled a few love lines to a love.

I had transferred from Suomi College to Augsburg College, in Minneapolis, another Lutheran college, feeling that I wasn’t being challenged academically at Suomi and wanting to experience life in the big city. When I got to Augsburg, the academics were very challenging. I began to write more poems and to read poetry books. I remember sitting in a park near the University of Minnesota campus longingly writing a longing love lyric to a boy in my American Lit class on whom I had a crush.

The girls in the dorm started to call me “our intellectual,” and one girl even gave me a book about science and philosophy that I couldn’t understand. I was glad she considered me so smart as to be able to understand this dense writing. However, my sentimental teenage self had been badly educated; in my American literature class, I did a paper on Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, failing to see its sentimentality. I got a D+, my first–and last.

But times were hard on the Marquette Iron Range, and my father had been demoted from the shops to the diamond drills, where the Company was exploring for beds of iron ore, and so I left Minneapolis and transferred to the state university near my home, Northern Michigan University, where I majored in English.

My first paid writing job was when I was appointed the editor of the college newspaper, The Northern News, during my senior year. Before I got the job as editor, I was a feature writer, and it was in that position that I first got into trouble for my writing. I wrote a feature on us commuters, where I used the term “Negaunese,” a term one of my drama professors, Dr. James Rapport, used to describe the U.P. brogue that people from the area speak. All the commuters ostracized me. Only Jimmy would dance with me at the Venice Bar and Roosevelt bars in Ishpeming, where we college students hung out, doing the twist on weekends. The next issue of the newspaper was filled with irate responses to my feature.

Thirty years later, people still tell me they remember me as that traitor who wrote that article about commuters. I recently reread the article and still view it as a decent attempt at satire being used to argue for social change (e.g., the commuters were being ostracized and ghettoized and the university should do something about it). I was to attempt satire again, when I wrote my first novel years later.

Now I have studied writers in my books, Understanding Those Who Create and “My Teeming Brain”: Understanding Creative Writers and I realize that many writers get into trouble for their writing. When they merely think they are telling the truth, they offend people. Kathleen Norris, in her book, Dakota, commented on the tendency of local historians to “make nice,” to overlook truth and to whitewash, through sentimentality and nostalgia, the struggles of the families of her area, the prairie towns. This is a tendency I try to avoid in my writing.

People think my fiction is true, that the stories I tell are stories about me. Well, they are and they aren’t. I have no qualms about altering.

Facts aren’t as interesting as the imagination. Both my novels are purely imaginative and writing from the imagination is very freeing.

If you write fiction to stick to the facts, you’re very restrained. As they used to say at the top of those old radio shows, “Any resemblance to persons living or dead is purely coincidental.” This tendency to be frank has not left me as I’ve aged.

I still get into trouble for my writing, and when I speak to high school writers, they often come up to me afterwards and tell me about the underground newspapers they’ve written for that have been banned when “I was just trying to tell the truth.”

The next fall, my senior year in college, I was not only a player in the political life of the university, for as editor I was expected to write editorials and to have opinions, but I seemed to have gained confidence.

The English faculty nominated me for a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship and to my surprise, I made it through all the interviews to become a national alternate.

I graduated Magna Cum Laude. I wrote poems and more poems and was dating, among others, a poet, an older student, a veteran, who loved literature and taught me a lot. He used to say I looked like Simone Signoret. Boy, I loved that!

That is the same year that the novelist Erica Jong, who attended Barnard College, received a Woodrow Wilson, and she based her novel, Fear of Flying, on experiences gained then.

I often joke and tell people that if I had gone to Barnard or some other private college, perhaps I would have won a Woodrow Wilson, and I could have written my own Fear of Flying.

One of the professors, the Pulitzer Prize winner Russell Nye, on my interview committee down in Ann Arbor at the University of Michigan, had family in the Upper Peninsula, and he kept telling all those other professors grilling me on my knowledge of literature to let up, “she’s just a kid from the U.P.” My essay was what got me to the finals, they said. I vaguely remember that essay being about how close reading of the Bible had helped me in close reading of texts. I don’t have a surviving copy.

That senior year at Northern also introduced me to a professor of modern literature who taught me how to read text closely. Many people reading this will remember Mr. Richer and “Araby” and how we had to read it over and over again. Now we educators call his methodology “teaching for deep understanding,” where depth not breadth is the goal.

The faculty at Northern Michigan University also urged me to change from my major of secondary education and to apply to graduate school with the aim of getting a Ph.D. in English.

The faculty at this state university in the north were true mentors and exemplars.

For the next seven years my writing was on hold as I finished up a Master’s degree in English at Kent State University where my new husband had started as a freshman. He and I had a baby boy, Steven, and we lived the married student life in campus housing, where he filled our soup pot with rabbits shot with his bow and arrow in the field between the apartments and campus. His love of the wild outdoors and my lonesomeness for the Upper Peninsula led us to move back there, where he studied geography and regional planning and I taught as an instructor in the English department.

A second child, our daughter Denise, was born, a year before he finished his Master’s degree. He got a job as a regional planner in South Dakota and we moved for his job.

The existential choice made here was a typical life choice of professional and most women. Mary Catherine Bateson, in her book Composing A Life, detailed the uprooting and upsetting and professional compromise of women following their husbands around the country. My life was no different than theirs. And I was glad to do it.

This ended the 26 full years I lived in the Upper Peninsula.

I had made sure that I obtained my teaching certificate before we left Michigan, but I was “overqualified,” meaning too expensive, unhireable at any high schools near our residence of Watertown, because I had six years of experience and a master’s degree. I decided to retrain and received another master’s degree, in guidance and counseling, from South Dakota State University. I worked as a high school teacher, guidance counselor, and school public relations administrator, in Florence and Brookings, South Dakota for two years.

The time in South Dakota was a time to look at myself and wonder. The first year there I didn’t have a job, and I remember my husband bringing a woman he had met over for lunch. “You’ll really like her,” he said. I fixed tuna fish salad and wore one of those hostess gowns that were popular in the early 1970s. When they came, I noticed she had great legs in high leather boots below a fashionable miniskirt. I still remember schlepping lunch to them in that nightgown, while they talked business.

That is when I realized I needed to work, to have some serious occupation besides mothering and wifing.

I had tasted professional respectability as a college instructor in Marquette. I wanted validation. I wanted a forum where I could work out my thinking. I began to write poetry and short stories seriously and to practice writing seriously and saw my first submitted story and my first submitted poetry published in the South Dakota Review. The writing became necessary as a means of validation and of self-therapy. That is, now that I didn’t have college teaching, where, with my speaking and thinking out loud, I vented my thoughts and worked on my ideas, I had to write them down. I still use writing to heal myself.

Several other catalyzing experiences happened in South Dakota, which freed me to put my poems to paper. One was participating in an acting workshop with the Minneapolis Children’s Theater Company, where I had to fall back into someone’s arms, trusting that the person would catch me. The actor’s name was John, and later he kissed me, a married woman. I felt released. The physical led to the emotional and the poems started and haven’t stopped yet. I wonder where he is.

For a rigid and shy Finnish American, this was a very difficult thing to do; I couldn’t trust in my words, my verbal aces and barbs, to get me out of this touchy-feely situation, but had to trust silently and physically.

This experience seemed to free me in some strange and miraculous way, and the poems poured out.

I told my friends and husband I wanted to practice, practice, practice, and that I would write a poem a day. I remember just after going to bed one night, my husband asked me, “Did you write your poem today?” I hadn’t, and so I got up, went into the living room, and wrote a poem about a fly I had killed in the sink. Other workshops in gestalt therapy taken while I got my counseling degree also helped me break through my critical self censorship to put words on the page and to take myself seriously as a struggling writer.

The stresses on the institution of marriage in the early 1970s, where sexual freedom and expression were touted and exhibited, also played a part in my needing to write it down. One of my first poems illustrates my struggle, as a young mother, to find space and time to be a serious writer.

During that time, I had a poem published in a new little magazine called Jam To-Day that a writer friend at South Dakota State University told me about.

The presence of other poets in South Dakota helped me learn what a budding poet had to do: submit, submit, submit, work, work, work, even if the work is rejected.

It was a poem about the last time I saw my father, Christmas of 1973. He died on April 1, 1974.

We moved from South Dakota back to Ohio, near my husband’s home, where he took a job working with his father in the furniture sales business. I began work on a Ph.D. at Bowling Green State University. Finally.

My work in English at the Master’s degree level, and my subsequent teaching of English at a university had led me to realize that I didn’t want spend my professional life teaching freshman English with its interminable flow of papers to grade, nor did I want to spend my life reading and writing criticism of literature.

I know this was nervy to think, but I wanted to write literature, not critique literature.

I decided not to get a Ph.D. in English, but to get one in educational administration and supervision. I thought I could run a school as well as any coach. Besides, an administrator’s pay is better. I’ve never regretted this decision, although my friends and professors at South Dakota State University thought I would be better suited to a field like educational or counseling psychology if I were going to go into education for my Ph.D.

I have subsequently written books and articles, and taught undergraduate and graduate students in each of these fields, proving you don’t have to have a degree in it to publish in it.

The children and I lived in Bowling Green, Ohio for nine years; their father lived there for five. They attended elementary and high school there.

While in this fine town, I became involved and friendly with the writers, the literary community surrounding the MFA program at Bowling Green State University, and continued publishing poetry and short stories.

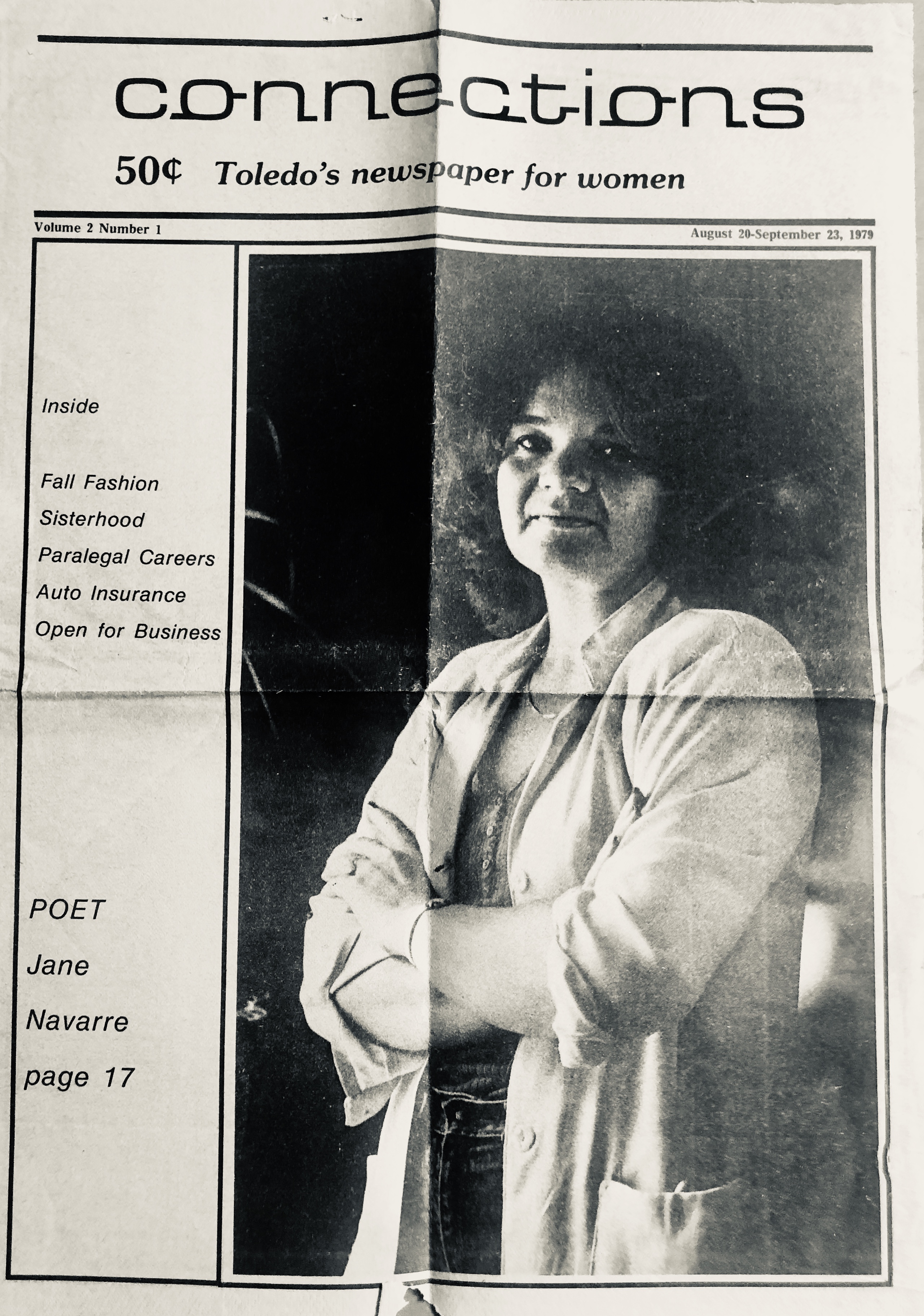

The Toledo Poets Center founders, Joel Lipman and Nick Muska are also close friends. I was even featured in a local newspaper as “A Poet Nearby”.

Other literary experiences were at writers’ conferences, the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference in Vermont, and the Aspen Writer’s Conference, in Colorado among them. The Bread Loaf Conference was rather intimidating and snooty, but I got to study with Toni Morrison, and the Aspen Writer’s Conference gave me settings for future fiction projects and friends with whom I still correspond. I met Raymond Carver there. He was with his girlfriend, Tess Gallagher. He asked to see my work and later nominated my fiction for the Iowa Short Fiction Award. (I didn’t win but I’m still honored.)

I even founded a small literary press, Piirto Press, that was in existence for seven years, which published sets of poetry postcards and poetry chapbooks. I self-published a well-received chapbook of poems about parenthood, mamamama (Sisu, 1976). As a job while I was in graduate school completing my work, and doing research on my dissertation, The “Female Teacher”: The Feminization of the Teaching Profession in Ohio in the Early Nineteenth Century, I became involved in the National Endowment for the Arts Poets in the Schools program, through the Ohio Arts Council.

I did writer’s residencies in Ohio schools in the late 1970s and early 1980s. During those years I also taught as an adjunct professor in the women’s studies program at Bowling Green State University and worked in the affirmative action office.

While finishing my dissertation, I was contacted by the placement office. Would I be interested in a position as consultant for education of the gifted programs in Hardin County, about 60 miles away? Yes. I went to the library and read all I could find about smart children (there wasn’t much then) and I interviewed for, and got the position.

It was February 14, 1977, when I began the day job, the career, I still have today, my career in the education of the talented. Little did I know that call was to be so auspicious. I still am employed in the field of the education of the talented. I worked in Hardin County for 2 1/2 years, and then I took a similar position, up over the border, 60 miles north, in Monroe County, Michigan, as a coordinator for gifted and talented programs with the Monroe County Intermediate School District. At that time, my marriage broke up.

I continued to write and to publish and to be involved in the literary communities of Ohio. I was awarded an Individual Artist Fellowship of $6,000 in fiction in 1982. What a moment that was, opening my mail and seeing that news. That review panel of out of state writers didn’t even know me! They had faith in my talent and they didn’t even know my name. I remember taking my children out to dinner at Bowling Green’s fanciest restaurant, as a celebration, when the check arrived. But the Individual Artist Fellowship was more than money to free me up to write. It was validation that perhaps I could write that novel I’d been saying I wanted to write.

That summer my children were set to spend a month with their father and his new wife in Port Clinton, Ohio. I was on vacation from the Monroe County, Michigan job. I thought I’d take a road trip, drive across country all by myself. I mapped out a route that had me stopping overnight with old friends each day, as I would work my way to Port Townsend, Washington, to the writer’s conference there. I would have adventures along the way, be a modern, free woman in her car.

I might pick up a cowboy at a bar in Montana. Who knew what adventures would befall me?

My friends thought it sounded like a great idea. I called my mother, telling her of my plans. She said, in a quiet voice, “I thought you wanted to write a novel. Isn’t this a good time to do so, without the kids there?” I ranted and raved about how I have never taken a vacation by myself, about poor me, the single mother, with two kids, working her fingers to the bone, commuting 120 miles a day, and now? What nerve she had to suggest I actually put my fingers on the keyboard and try my skill. The next morning, I called her at 7 a.m. and said, “You are right. Thank you.” And I applied my posterior to the chair, put my fingers on the keyboard, and began.

That summer stands out as one of the most creative in my life. I wrote my first novel, The Three-Week Trance Diet, while I was blessedly alone in my own house for the first time, with our Chesapeake Bay retriever, Maynard Ferguson’s head on my foot.

It was the first extended period of solitude I had ever had. I was forty years old.

I remember writing ten pages a day, every day, chortling at the typewriter as unbelievable, funny, satiric and I hoped, truth-telling characters came out of my mind through my fingers onto my IBM Selectric. I had the practice of having written a dissertation, and so writing a novel, a sustained project, was not as difficult as I had believed. I couldn’t believe that plot was coming out so automatically.

Later, one of the reviewers called it “intricately plotted.” It must have been all those years of reading novels, novels, novels.

I wrote the novel in a month, and the first draft was pretty much the final draft.

It was easier than I ever imagined it would be. Where is the tortured writer crumpling up pages and throwing them into the wastebasket, agonizing over each sentence? That writer wasn’t me. And it never has been. Still isn’t.

I began to send the novel around, hoping to interest a literary agent. No luck. I have never been able to interest a literary agent, although one did contact me when I got the Individual Artist Fellowship. When he found out I wrote short stories, he told me to write novels, novels, novels, and more novels, and then he might, he just might, be interested in seeing my work.

I also entered the novel into the Carpenter Press First Novel contest. Carpenter Press is a respected small press that publishes fiction, one of the few that does. It was their tenth anniversary, and they wanted to celebrate by publishing a first novel. I also put together the collection of poems called Postcards from the Upper Peninsula. It was published as a chapbook by Pocasse Press in 1983.

The Upper Peninsula was, and still is, magical to me, though I live in Ohio, and the collection reflected that.

I wrote at night, late, sitting up in the living room, after everyone had gone to bed, during the late 1970s. At the time the chapbook was published, the year 1982-1983, I was also appointed to the literature panel of the Ohio Arts Council, where we read grant proposals by small presses and literary journals, and helped to fund them. This was a lesson in the frustrations small presses have in publishing and staying afloat, especially small presses that publish poetry.

My novel, The Three-Week Trance Diet, won the Carpenter Press Tenth Anniversary First Novel Contest, over about 70 other entries. Carpenter had several judges who judged the manuscripts anonymously, and the book won by a fraction of a point. It was published early in 1986, with a copyright of 1985.

At that time I had changed jobs, and was now living in New York City, the principal of the Hunter College Elementary School. If risk-taking is an aspect of the creative person’s life, I have been told that the risk I took in just picking up and moving, dismantling a four-bedroom house in Ohio and moving to take a job on the Upper East Side of Manhattan with no idea of where I would live or with whom I would be friends, could perhaps be called such.

At that time I had changed jobs, and was now living in New York City, the principal of the Hunter College Elementary School. If risk-taking is an aspect of the creative person’s life, I have been told that the risk I took in just picking up and moving, dismantling a four-bedroom house in Ohio and moving to take a job on the Upper East Side of Manhattan with no idea of where I would live or with whom I would be friends, could perhaps be called such.

After publication of The Three-Week Trance Diet, I immediately began writing another novel, The Arrest.[1] The Ohio Arts Council appointed me chair of its literature panel, and I flew back from New York City to Ohio for three years for the panel meetings, seeing my friends in Ohio and staying in touch with the writing community.

I continued to write poems and short stories, some of which were published. A short story manuscript was a finalist in the Iowa Short Fiction contest one year. I also began a nonfiction book, called Principal, about being the principal of a high-pressure, multiracial, urban school for high-IQ students. All three of these, the short story manuscript, the novel, and the nonfiction book remain unpublished, though the novel has been nominated for the Pushcart Publisher’s Award and it has been a finalist in several contests, and the nonfiction book was sent to Hollywood by a friend who thought Jane Fonda’s people might be interested. Can you imagine that? I can’t. She wasn’t.

When I got this job I still have, in Ohio, my old stomping grounds, I came back to my original profession, college teaching. My writing continued; I always write poems, for myself, for friends, and I submit to the occasional journal that asks me.

Life in this quiet existence in a quiet college town has helped me publish two long nonfiction books, Understanding Those Who Create, with Ohio Psychology Press in 1992, and a textbook, Talented Children and Adults, with Macmillan in 1994.[2]

I won’t talk much about my scholarly writing here; just know that it is grueling, difficult, and detailed.

Everything has to be proved with supporting studies and references. For the Macmillan book I had an acquisition editor, a production editor, a copy editor, an art editor, a photo editor, a marketing manager, and their various assistants calling me and asking me things. I had to obtain permissions and releases. I had to read, understand, and summarize many books and articles. Whew.

I was very tired when it was all over. Many professors who write textbooks are at universities which have graduate assistants and teaching load reductions, but the place I work is a small college and doesn’t have those amenities for professors doing research and writing. I did those two books in three years, and I am proud that I was able to do that.

Don’t ever put down a person who writes a textbook. It is very hard work and requires a lot of stamina.

In 1990, I applied for and was given a Fulbright-Hays study grant to Argentina in 1990. My project was to write a cycle of poems, and I did so. A manuscript of my travel poems to Argentina and to the Near East and Southern Asia won an Individual Artist Fellowship of $5,000 from the Ohio Arts Council in 1993.

Another thing that happened when I moved to Ashland was I went back to the Lutheran church. I felt a real spiritual yearning after the collapse of my job in New York City, and when I attended the Trinity Lutheran Church on Center Street here, I found myself weeping at the songs and at the liturgy. My mother said with great assurance, “Don’t worry. That’s just the Holy Spirit working.”

For some reason, my sense of being a Lutheran and a Finnish-American of the third generation came together as I joined the choir and sang in a women’s trio. I had left the church as a cynical intellectual in the early 1970s, and neither of my children were confirmed, though they were baptized. But I found my way back to the spiritual home where I had spent my youth in Luther League, Bible Camp, and two church related colleges. The landing has often been rocky, and often comforting.

My problems are those of making that Kierkegaardian leap. But that’s another autobiography.

I have been teaching spiritual autobiography courses here and there and they have been nothing short of miraculous in the sharing that has been engendered by communal writing about deeply meaningful experiences.

As we age, they say we get more concerned with ultimate meanings, and become much like we were during the pure searches of our mid-teens. My quiet life as a professor and writer, with my kids grown and gone to their adult lives, has fostered the thoughts written down here during this year of my life and at this place where I live now, as have my researches for the books I write. None of us knows what will happen next.

“This I knew and this I thought.”[i]

Runo 22, Kalevala

MEDITATION AT HELEN LAKE, MICHIGAN

Smoky vapor off the lake.

Remnants of coals stirred

in the stove in the outdoor fireplace

rekindle in deep ash.

The sun is arriving again.

Leaden pewter clouds lay scattered

across the golden luminescent east.

Above, patches of blue

promise a fair day.

The dog Jessie sighs in her sleep

while far-off geese cry at breakfast.

The handle of the cup is cold

but the coffee is warm.

Earlier, rising to light the wood stove

I heard the crackle of flame begin

with crumpled newspapers and kindling.

Then I cuddled back into the drowse

of my warm sleeping bag.

Now, small birds dart in the spruce trees

in front of this primitive porch.

They do not stop long enough

for me to identify them.

The deep pleasure in writing

what I sense overtakes me

here in the morning at the table.

Wild phlox, goldenrod, nod in dawn air

catching the magical red-orange light.

Blowing east, the mist begins to dissipate.

The perfect reflections of clouds

and birch shore laden

with fern, moss, and brush

paint the still still lake surface.

The cabins on the other side slumber,

though one burned a bright beam

in three directions last night

while I swam naked

after sauna in moonlight.

Pure elements—

earth, air, fire, water coalesce—

My mind drifts as is its habit

to my grown children

gone to their lives but not

from encompassing protection

of loving thought

and the questions—

Now I have finished this last book

how will I fill time?

What meaning will life take?

Where will the path go next?

When or if I should retire?

In this exquisite natural tranquility

one discovers in middle age

is wisdom nascent?

I wish I knew that bird’s name—

Hopper, Flutterer, Splasher-In-The-Water—

This peace is joy.

END

[1] Both these novels are available, cheap, for the Kindle and the Nook.

[2] Understanding Those Who Create went into a 2nd edition published in 1998; then its name was changed and it was published as Understanding Creativity in 2004. Talented Children and Adults went into a 2nd edition published in 1999 and into a 3rd edition in 2007 (Prufrock Press). I also published “My Teeming Brain” : Understanding Creative Writers in 2002; Creativity for 21st Century Skills: How to Embed Creativity into the Classroom, in 2011; and Organic Creativity in the Classroom: Teaching to Intuition in Academics and in the Arts, an edited book, in 2014.

[i] The quotations to introduce the poems in this section are from the Kalevala, sometimes called the epic poem of Finland, but more accurately, a collection of anthropologist Elias Lonnrot’s field collection of songs, lays, charms, and magic spells from the 1850s. The translations from which these quotations come are the Keith Bosley translation (Oxford University Press), and the Francis Peabody Magoun translation (Harvard University Press).

Publication history:

- Excerpts from A Location in the Upper Peninsula (1994). New Brighton, MN: Sampo Publishing.

- Published in (1996). Piirto, J. (1997 with 1996 date.) Why Does A Writer Write? Because. Advanced Development, 7.

- Piirto, J. (2008). Why does a writer write? Because. Mensa Research Journal, 39(1), 7-18.