Don't Fence Me In

Here is an interview survey I filled out for Susan Keller-Mathers’ research for her doctoral dissertation in 2002.

Extraordinary Women’s Journeys to Creative Accomplishment

This survey is adapted with permission by Susan Keller-Mathers from Reis, S. (1987). Gifted female Questionnaire. Storrs, CT: National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented at the University of Connecticut.

Susan Keller-Mathers: The purpose of this research is to examine womens’ perceptions of their life’s journeys to extraordinary creative achievement. By completing and turning in this survey you are giving your consent for the researcher to include your responses in her data analysis. Your participation in this research is strictly voluntary, and you may choose not to participate without fear of penalty or any negative consequences. Individual responses will be treated confidentially. No individually identifiable information will be disclosed or published, and your information will be reported as a case study. If you wish, you may request a copy of the results of this research by writing to the researcher at:

Susan Keller-Mathers / International Center for Studies in Creativity at Buffalo State College

Please note: For this research, creative accomplishment is defined broadly as any unique and useful outcomes or products you have produced. This may include areas traditionally thought of as areas of creative productivity such as works of art, plays, scientific discoveries and inventions but also includes a wide range of other areas such as writing, singing, software design, cooking, engineering, and outcomes such as impacting others through mentoring, teaching, parenting or leadership roles.

SK-M: What is your current career or avocation (if retired, what careers, jobs have you had?)

Piirto: I am a professor of education, teaching courses to master’s degree students who are getting their licenses in the education of the gifted and talented, and teaching doctoral students in educational leadership in qualitative research methodology.

SK-M: What are the main reasons you chose your occupation or pursued your avocation?

JP: I had been on the track to get a PhD. in English, and in 1963 was offered a full fellowship to Michigan State University to do that. I got pregnant. My plans were derailed. After our son was born, my new husband and I decided to go to Kent State University, where he would begin as a freshman, and I would get a master’s degree in English. I was a graduate assistant there from 1964 to 1965. Then I took a job teaching high school English from 1965 to 1966.

I got my master’s in English in 1966. We moved from Kent State University back to Northern Michigan University, where I began as an instructor in the English department, and he became a geography major, eventually obtaining a master’s degree in regional planning. I taught in the English department there, on tenure track, for 5 years. We then moved to South Dakota, and there I began my work on a master’s degree in guidance and counseling. We then moved back to Ohio, in 1971, and I applied for doctoral programs. People thought I should go into educational psychology or English, but I decided to go into educational administration. I didn’t want to write and read literary criticism or be a literary critic. I wanted to write literature, not study and write about it. While in South Dakota, I also began to write seriously, and to publish poetry and fiction in literary magazines. My decision to go into educational administration had to do with my feminist nature – I thought I could run a school as well as any coach, and I also thought that educational administration needed more women in it.

Our class at Bowling Green State University contained 7 women, all of whom believed as I did, so we had a fine community of potential women school administrators there. I continued to write, read, and attend literary events and became fine friends with people in the writing MFA program at Bowling Green. They became, after I finished my Ph.D., my “true” friends, more than my friends in educational administration, probably because our personalities were similar.

SK-M: In retrospect, do you feel you made the right decision?

JP: Yes, definitely. The decision to go into educational administration instead of educational psychology or English has been a good one. The degree is a generalist degree, in certain ways. I can do educational psychology because of my master’s in guidance and counseling, and I can do English because of my master’s in English literature. My friends back in the English department have spent 30 years grading freshman essays! Yuck! They are burned out. I am in my sixties and have no plans to retire, as my job is very interesting and still provides new challenges. I do miss teaching literature, and I do miss having a community of people who love and know literature, as one would in the English department.

SK-M: Do you wish you had chosen a related field, or an entirely different field? Is so, what field or area of study would you have chosen and why?

JP: I debated going into clinical psychology, and am now considering getting another degree in depth psychology from the Pacific Institute. I like dream work, and I like mythology and would like to study more about them. But I am doing that in my spare time, with various friends, mentors, and groups. I also debate getting an MFA in creative writing, just for myself – this morning I was thinking I should just apply to a top writing program and see whether I can get in (they must have some constraint about not being age-ist), and then see what happens. It would be fun to indulge in something like that.

SK-M: What are the ways you have been creatively productive? What have you accomplished?

- I have been creatively productive in the literary sense. I have published over 100 poems in literary journals; my novel was chosen over 70 others in a first novel contest, and it got published; my short stories have been published; I am always writing, revising, and sending out. I feel my true self is expressed in this regard. I also have a novella, a novel, a play, and a screenplay in the drawer, as well as many poems, essays, and a few short stories.

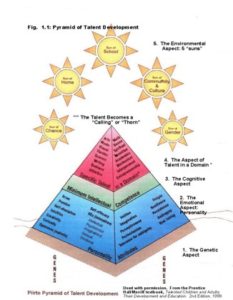

- I have also been creative in my scholarly work. My book, Understanding Those Who Create, is in its 3rd edition, and I keep working on my theories there. My Piirto Pyramid of Talent Development has been the theoretical framework for my research. My book, Talented Children and Adults, in its 2nd edition, is, in some ways the work I am most proud of; because it is so dense, I had to synthesize, remember, read, and recall, hundreds of sources in order to do it. It might not go into a third edition because of sales, but I am still very proud of it. [Third edition was published by Prufrock Press in 2007/] My book, “My Teeming Brain”: Understanding Creative Writers, is a work of the heart, as I combined my inside knowledge of the creative writing profession and my work in creativity, to produce it. Books

- I am creative in my teaching. I continually work on designing new ways to teach old things, and I think I am quite successful. I have my doctoral students fingerpaint their studies. I am active in the Arts-Based Research group. I do workshops on creativity in which I combine depth psychological principles and my work on the creative process. I bring these to all my classes. I taught the curriculum course a couple of times a few years ago, and brought in many of the activities and exercises I use in the creativity course, and things I learned in teaching writing and spiritual autobiography. A former student in that course (not majoring in talent development education) whispered to me as she was lined up to get her master’s diploma and I was seated with the faculty (“yours was still the best course I had in my Master’s degree”).

SK-M: How do your creative accomplishments relate to your personal life?

JP: My creative accomplishments direct my personal life. How can anybody not live their creativity?

SK-M: In what ways did your family encourage/discourage your creative abilities?

JP: My birth family? My mother is very creative herself, and so are my sisters. We were never discouraged. Our extended family on my father’s side is musical, and our childhood Saturday nights at grandma’s for sauna, are filled with memories of everyone gathered around the piano, singing. My own children are musical. I encouraged lessons, and my daughter attended the La Guardia High School for the Performing Arts in saxophone, and my son was in a famous drum and bugle corps, and still plays in a rock band. Reading was also a part of my life. My mother’s house is filled with books, and she herself is a reader; at 87 and 61, we often spend quiet days in the house together, reading in separate rooms. My house is filled with books as well, and I am bereft if I am not reading, if I don’t have several books going, at once. This is the most salient predictive behavior for writers that I found in my research – they are incorrigible readers.

My marriage family? My ex-husband isn’t a reader, but he didn’t discourage it. I began writing seriously during the marriage, and he encouraged me, often listening to my poems. He also called them “you and your little poems” during periods of fighting, but on balance, I would say he encouraged me. He also moved to the town (Bowling Green) where I could get a Ph.D., and did his work from there, in the 1970s, until we were divorced in 1979.

SK-M: To what degree did your occupational field or area of creative accomplishments agree with the aspirations that your parents and family had for you?

Not at all Somewhat Completely Agrees

1 2 3 4 5 6

Please elaborate:

JP: My family would have wanted me to be anything I wanted to be. There was no pressure to be or discouragement not to be. I would say that the parenting style was authoritative, with my father encouraging me to use my brains, my smartness, to go to college and to go and make money! He always bought me baseballs, baseball bats, and such, when I was in love with baseball as a kid (softball, really), fixed my bike, brought me “steelies”–steel ball bearings– from work (to play marbles with and to lose to the boys in the neighborhood). I’m sure they (my sisters and mother) are proud of me, even though they don’t read my work — . But that’s OK. My younger sister has published two books on advertising in business, and has aspirations to write mystery novels, and I’m sure she will. My middle sister is creative in fabrics, weaving, quilting, and such. We just all encourage each other.

SK-M: How does life today compare with your dreams for your future when you were younger?

JP: Life today is great! A colleague who does creativity workshops with me and I were standing under the awning of the hotel in Corpus Christi where we were doing 2 days of workshops last week. As we waited for the shuttle to come up to take us to the seafood restaurant where the conference organizers were meeting, he said, “Piirto, you have a good life!” And I do. I’m an honored professor (Trustees’ Professor) at my university, and there are only four who have been named such in the 125 year history of the university. I get to travel abroad (this summer I’m going to Australia to present two sessions at a conference). My kids are grown and gone, and are, most of the time, happy and productive. I live alone in a big old house, with time to write. (I am writing this in the morning before I go to work this afternoon—I teach the counseling course tonight to 7 interesting women teachers).

My dreams for my future, would, I suppose, have included a happy marriage, but that hasn’t been possible. I feel lonely sometimes, but not overly lonely. Most of the times I treasure my solitude. I am choosing to go alone to Australia this summer just because traveling alone ups the creative intensity and naiveté that helps me in writing. I have a reservation at a beachfront bungalow on the Coral Sea, where I can picture myself having a glass of wine, listening to the sea waves roll in, watching the sky, writing. If I were with someone else (and people have offered to come with me), I would miss this intensity.

SK-M: To what degree did your occupational field or area of creative accomplishments agree with the aspirations that you had for yourself?

Not at all Somewhat Completely Agrees

1 2 3 4 5 6

Please elaborate:

JP: I would like, of course, to have more recognition as a creative writer, but then I look at the statistics. I am listed in the Directory of American Poets and Writers, as both a fiction writer and a poet. 1,100 writers are listed in both. This is .0000055 of Americans. And I am one of these! This is quite amazing when you put it in terms of statistics. I realize the Sun of Chance (on my Piirto Pyramid) is the reason I am not more well known – and not my lack of talent. Who knows? Perhaps something will hit.

SK-M: Please list the most exciting, rewarding achievements in your personal development.

JP: Personal development? Becoming a mother. What an adventure being a mother is. My first book of poems was called mamamama, and it celebrated this. An article about me in the Toledo Blade in the 1970s, called “A Poet Nearby,” featured me and my daughter. Here’s one of my poems about it.

POETMOTHER

the afternoon is calm

silence time to write

the paper is green

like the summer

the mind floats into

itself like distanced

birdsong with images

bright as the kitchen sink

the polished coffee table

slowly right there

the words twist from

the images and

the fingers take dictation

fast and willing

then the back door

slaps and his feet

in dirty sneakers tramp

then the voice begins

“Mom where are you

I can’t find anyone

to play with

take me fishing

“where’s the juice?”

(mom I want)

(mom I own you)

“You can’t catch me!”and the front door crashes

and a little girl runs

shrieks laughing through

the shatter

I sit up

try again

for stillness

SK-M: Please list the most exciting, rewarding achievements in your professional development.

- Being nominated for a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship in 1963 and reaching national alternate status even though I came from a rural regional state university.

- Being chosen to be the editor of my college newspaper in 1962-1963.

- Getting fellowships to any college I applied to in English literature.

- My Ph.D.

- Having my first poems and first stories published in literary journals, and my first novel win a contest and get published.

- Becoming an advanced trainer for Mary Meeker’s Structure of the Intellect and conducting workshops throughout the land.

- Being the principal of one of the most elite and well known schools in New York City.

- Becoming a Trustees’ Professor.

- Writing and publishing Understanding Those Who Create

- Writing and publishing Talented Children and Adults

- Writing and publishing “My Teeming Brain”

- Being asked to speak at, and even be a keynote speaker, at various education and psychology conferences.

SK-M: What were the major events or circumstances in your life that had the greatest influence on your creative accomplishments?

JP: I have always been inspired by love. In my work, I call it “The Visitation of the Muse,” and it is a common way that artists and creators are inspired. I am no exception. I really don’t want to tell those stories yet. Here’s a poem that may suffice.

BETWEEN THE MEMORY AND THE EXPERIENCE

between the memory and the experience

between the photograph and the periphery

with intuitive and parsed phrases

for salvation, doubt and irony

run over by pale images become sharp

twisting and turning in synapse of wire

sad more than joyful

the years of the fog of life

brooded upon as if the magi of words

could clarify meaning like heat to butter.

what has it meant?

truth told a lie

by telling like a hurricane

by the process itself a swirl

wind gathering water to make waves

deep within the basin of oceanic consciousness

between the memory and the experience

“This novel is about the divorce,” I tell him

offering the code from a cardboard box in my red trunk

“And this is about being a mother.”

the blue folder of unpublished truth

no one would know unless I told

My love affairs have inspired me, my love for my children, my husband, and my family have inspired me, my love for nature has inspired me, my love for God has inspired me, my love for my pets has inspired me, my love for thought has inspired me. As a result of this, I always include, in my creativity classes, a session on love and its power to inspire.

Several friends of mine have experienced whole new surges of creative energy when they fell in love later on in life, after they thought that sexual love was lost to them. Poets Joan Baranow and David Watts met at the Squaw Valley Writers’ Conference, fell in love, and wrote a series called “Epithalamium” to each other. Joan’s part of it won her an Individual Artist Fellowship from the Ohio Arts Council.

Poet James Tipton’s muse, novelist and memoirist Isabel Allende, wrote an introduction to two of his collections of poems. Here is what she wrote: “One day, during the summer of 1994, I received a letter from a stranger,” who wrote to her after reading her work, from the top of the Andes near Machu Picchu. He wrote again a few weeks later, with a story about an alcoholic woman in a wedding dress scavenged from a garbage can, who was arrested making love on the railroad tracks with a stranger from a bar. He offered to find out more. Allende said: “I was hooked, not only by the fascinating mystery of that woman, but mainly by the man who had the intuition to send me that precious gift.” She replied, and a correspondence began.

Tipton would send her several poems a week. Allende’s daughter had just died, and “I found myself waiting for the mail with a secret anxiety that I did not want to admit even in the silence of my heart.” She began to be very interested in the man and his poems: the poems “would go deep down inside my sorrow and swim like small fish.” The poems would bring her “to their soft light . . . like shadows, like sounds I heard in sleep, like ships that slip unnoticed into the port at night.” This correspondence took place and finally the two, the poet and the novelist, met, over a year after Tipton began the correspondence. Allende is married and lives over a thousand miles from Tipton. “And thus, one poem at a time, our friendship evolved slowly and the stranger became a dear friend.” Tipton’s book, Letters to a Stranger, won the 1999 Colorado Poetry Book of the Year award.

SK-M: Can you tell me a bit more about your passion for writing? For example, In what ways are your writing central to who you are? In what ways does your writing (and other work) inspire you?

JP: My passion for writing takes the form of a daily stint at my computer, or with a notebook, or with my dream notebook. Writing is central to who I am, as I do it every day. My writing does not inspire me — other people’s work inspires me. I read a lot (poetry, novels, nonfiction), and am inspired by poetry by people such as James Tipton and Mary Oliver. I feel quiet, meditative, and wonder whether I could ever write so. I try to imitate. I write poems when I feel emotional about something. I have not written fiction for awhile, but am doing research for what I hope will be a historical novel. I have been writing creative nonfiction, and when I work on it it also quiets me.

I have been putting together manuscripts of my published and unpublished poems for contests, and that revision also quiets me and is meditative. Going through from beginning to end, slowly, making sure each word is what I want it to be, each rhythm also. I have been also composing a little music. The last piece I composed was in 4/4, about walking my mother’s dog on Christmas day. The tune just came to me as I was walking. I dream poems and tunes as well. I dream images. I try to trust my dreams and go with them. Recently I dreamt of a black butterfly in the pages of a book, and have been tracking down this imagery. I read Hillman and Jung. I am teaching a seminar on depth psychology and education, and monthly, my two post-master’s students (taking this as an independent study) meet at my house and discuss the readings. Last week it was Hillman’s Blue Fire. Next month it will be Psychological Types by Jung. My writing is such an inextricable part of my life that your questions don’t even make much sense — describe my passion? I live my passion — it is interwoven into my life — I don’t “plan” to write. I just do.

SK-M: You seem very determined to achieve and talk about how you are more disappointed that you have not become a famous writer. Can you tell me a bit more about your desire to achieve and what that’s meant to you throughout your life?

JP: I’m probably, as you say, “determined” to achieve in the sense that my work is intentional. However, the honors I have been given have not been sought, or solicited by me. Today I got an email from my undergraduate alma mater who wanted to nominate me for distinguished alumna. I never sought it nor have I solicited it. My desire to achieve is part of being a good girl, a good student. I also have failed in some areas of my life — I have a poor body image (as do most women), and I’m not nor have I ever been popular with men (whom I adore but they don’t adore me).

I suppose achieving in academic and creative ways is part of my trying to gain self-confidence. I do, however, count being a mother and a grandmother great pleasures and achievements.

My successful New York City professional daughter’s achievements delight me, and I talk for hours with her on the phone about the ins and outs and details of her work, as well as her own motherhood. My son’s achievements as a successful visual artists/ photographer give me great glee, and I hungrily collect his work and listen to the music he is composing for the rock band he plays in. He was recently asked to join a rather prestigious alternative band as bass player, and I am so proud of him I bloom inside. So — I guess the NFA (Need for Achievement) is part and parcel of our family makeup. I am proud of my sister, who’s written two books and is an award-winning videographer, and who has just done a project on the Nisei in her church and is submitting the video to contests.

Achievement is also its own reward, and an inoculation against despair, depression, and feeling sorry for oneself because one is not slim, beautiful, young, or attractive.

SK-M: Based on your life experience, what advice, if any, would you give to girls and young women regarding developing their creative potential?

JP:

- Get married young and have your children young. But have a college education first. (Wink.) Yes, to “fall back on.” Then you can concentrate, in your glorious forties, fifties, and sixties, on your own creativity.

- Get an advanced degree. No one can mess with a diploma!

- Don’t feel sorry for yourself. Just go out and do your work.

- Have an ethic of work and of care in doing your work. Work around your children and let them see you work and value your own creativity.

- Learn from the best. Attend workshops, seminars, and go to conferences. Network with them. Meet them. Don’t be afraid to show your work.

- Join groups of people who are doing the same thing as you are doing — a local writers’ group, a local artists’ group, a women artists’ group, and create friendships with these wonderful people, who will be with you throughout your career.

SK-M: How has either marriage (or relationships) and/or the birth of your children affected your creative accomplishments?

JP: Of course they have. See above. My marriage, relationships, and the birth of my children have been coded into metaphor in all of my work. In one of my essays, I spoke of how the artists uses the material of her life.

SK-M: How much free time do you have each day? (estimate)

JP: Depends on the day. I have weekends. I have mornings. I teach at night, to teachers taking advanced degrees. I try to work at home about 4 to 5 hours a day.

SK-M: What percentage of household work and chores do you do compared to your spouse/partner and/or other family members?

JP: I do it all. I also have a cleaning lady, and a yard man. I live alone.

SK-M: What problems do you encounter or have you encountered in trying to be creatively productive and maintaining a satisfying personal life? Please explain.

JP: No problems. I live alone. Grandchild lives in New York with parents. I have good friends here and away, and I see them when I can.

SK-M: If your current life is different from what you expected, to what do you attribute these differences?

JP: I really didn’t have conscious expectations; I just reacted to the present situations and wanted to have a professional career along with being a mother.

SK-M: What else do you wish to accomplish in the future?

JP: I have lots of writing projects. I would like to write the great Ishpeming novel, exploring the impact of the Cleveland Cliffs Iron Company on my home town and on Cleveland, Ohio, a sort of tale of two cities. I’ve written a long essay about it and when I go home, I go to the historical society and do research on it.

SK-M: Please discuss anything about yourself or your life that is important to you in regard to your creative productivity and has not been covered in this survey.

JP: I can’t think of anything just now. All the answers are coded in my work, and I’m not done yet!

PART II. FOLLOWUP PHONE INTERVIEW

BY SUSAN KELLER-MATHERS, 5/03

SK-M: Would you tell me about the process of writing the novel, The Three-Week Trance Diet?

JP: In 1982, I had just won a $6,000 Individual Artist Fellowship in fiction from the Ohio Arts Council. I had submitted short stories and I had only written short stories, but I had always wanted to write a novel because I am such a reader and I read novels and I wondered if I could write one. I had been recently divorced and my daughter and son were going to be living with their father for one month in a nearby town. I would be alone for the first time in my life for a month. I had plotted out a cross country trip to go to have adventures. I knew people all across the country, and I planned to end up at the Port Thompson writing conference in Washington. I have friends in Minneapolis, South Dakota, Colorado, and other places on the way west. I might even pick up a cowboy in a bar in Montana. I would be a single girl on the road having adventures. I called and told my mother what I planned to do.

She said, “But I thought you always wanted to write a novel.”

I said, “Mother, I work! I have this coordinator’s job and I drive 60 miles one way to my office, and I am taking care of the kids alone. I want to do this. It will be fun.”

“I always thought you wanted to write a novel,” she said in her quiet way. “Isn’t this a perfect time when you have a month alone?”

“Mother, you don’t know how hard I work!”

I even sort of hung up on her that night. I went to bed and the next morning I woke, and realized she was right. I called her up at 7 o’clock and I said “You are absolutely right. Thank you.”

I unpacked my suitcase and I started. I knew that if I were going to write a novel in one month, I had to really use my time. I wrote 10 pages a day, 7 days a week. My only companion was my dog. I would write with his head on my foot. I just used that alone time. I had the first sentence a month before. “Letitia Siwell crossed her swarthy legs and lit another cigarette.” Not quite as profound as Joyce’s first sentence in his story,

“Araby,” which I had memorized as an undergraduate: “North Richmond Street, being blind, was a quiet place, except for the hour when the Christian Brothers’ School set the boys free.” I had read so many novels that it really flowed out of me. Really automatically.

I didn’t have to outline. It was from all within inside and I would write and then I would take a walk and I would maybe see friends later in the day. It was one of the most perfect months of my life.

Then a fellow owner of a small literary press, Carpenter Press, sent an announcement that they were sponsoring a First Novel Contest. I put the announcement up on my kitchen bulletin board and contemplated the possibility. A writer friend of mine who was also a fiction writer also had seen the announcement. He said, “I am not going to pay for a contest. You shouldn’t have to pay for a contest.”

I said, “Well those poor small presses, they need to ask for reading fees. I don’t mind paying someone to read my novel.” I think it was a $20 fee in that summer of ’83. I paid the fee and sent the manuscript.

A few weeks later I accepted a job at Hunter College in New York City.

SK-M: How did you get to New York?

JP: Well I came to work one day in the spring of 1983, and I had been doing a creativity workshop at one of the 65 schools I served, and there was a note on my phone from my boss who was a very emotional woman. I liked her a lot, but she got emotional.

The note said, “I am trying to give a workshop and your phone keeps ringing. Stop your phone from ringing.” I said to myself that should be the switchboard. It was the switchboard ringing the phone into my office.

I got angry. “How can I stop my phone from ringing?” I said to the administrative assistant. I closed my door and I pulled out an ad that I had cut out from the NY Times for a principal at the Hunter College Elementary School. I had done my dissertation in women’s studies and I remembered that Hunter College High School had been a school for girls. I sat down at my Selectric IBM typewriter and wrote a letter of application. I called the placement office at Bowling Green State University and had my transcripts and references sent to Hunter College. And then I wasn’t mad anymore and I opened my office door, went out into the hall, entered my boss’ workshop with a smile, and did my job. I forgot about it.

Hunter called me in July of 1983 to come and interview after all their other avenues hadn’t paid out. The search committee still couldn’t agree. I got the job later on in the summer of ’83 and I dismantled my 4-bedroom house, had the obligatory rummage sale, had my 19-year-old college sophomore son became a landlord as we rented the house out, drove to NYC, and I started the job. He later told me, “That was a lot to expect from a 19-year-old.” I said, “I didn’t even think about it. I knew you could do it.”

After my first year there, I found out I won the First Novel Contest. I had just returned from an Education and Innovation conference in Westchester in the summer of ’84–where I had heard a young Harvard clinical professor called Howard Gardner give one of his first speeches on his new book called Frames of Mind— and I found a handwritten postcard that said, “You won.”

It pays to enter contests.

SK-M: It sounds like you often either look for opportunities and when you see them you apply for contests or fellowships.

JP: Right. Absolutely. Because “you can’t win if you are not in.” That is a gambling poker saying, and it is true. I have entered probably hundreds of contests that I haven’t won but I still have the fact that I won. This big one. Then you know I have had other grants and stuff like that you can’t win unless you apply. So I do apply. In fact, my taxman has a category called Contests.

SK-M: Oh wow.

JP: It is only 10 bucks, 15 bucks when you send them in and then you get a subscription to the literary journal for a year. You don’t win but you know it keeps me out there. And it can be viewed as a donation to support small press literature.

SK-M: You also mentioned chance happenings. For example, a father who came into your office and he was a book salesman and he gave your name to a publisher who wanted a paperback general text. And you met Jim Webb from Ohio Psychology Press and he asked you to write a creativity book. So people really ask you, but my question to you is why did you decide to take the chance to write things like that when you hadn’t done anything like that before.?

JP: Well I am a writer and so when I started Understanding Those Who Create I had been very interested in creativity. I took a graduate educational psychology seminar when I was doing my PhD and I focused on the educational psychology of creativity, where I did an initial lit review of the early thinkers on creativity and psychology. And so I thought I would come at it in an interdisciplinary way, because I was also a published literary writer, and maybe provide the artist point of view.

I just read tomes and books and studies about creativity. Take a look at the reference list. I mean writing Understanding Those Who Create in ’90 and ’91 I learned so much. There is something instinctual in my intuitive book planning. I knew I wanted to organize the book by domain of creativity. I trusted my instinct and intuition. I made an outline for the book proposal that followed my intuition to organize by creativity in domains of achievement and talent and not by some so-called g factor of creativity.

I have developed, over the years, the Piirto Pyramid of Talent Development. It has become the theoretical framework for my research.

This domain-based creativity approach was instinctual at the beginning because I knew, when I took the Creative Problem-Solving process training and took those workshops, I knew that wasn’t how I created. I created alone in my house with the dog’s head on my foot. I didn’t do criteria-finding and charts and pros and cons like they taught us to do in that fun but also dreary Creative Problem-Solving training–adding those things up. Brainstorming. Nobody I knew who was an artist even made it through the whole Creative Problem-Solving process, because they hated it so much. But that is what we were doing in gifted education. They defined divergent production as creativity. I knew divergent production was absolutely not creativity—it is a fun cognitive part–remember, it came from Guilford’s Structure of Intellect–but it omitted the emotional aspect of creativity.

When I took these workshops, I thought, “This is not me. This is not how I create.” What I did was and what I am still doing is what I call “organic creativity”– creativity arising from within, in the right conditions—I began collecting comments and quotations from creators within domains—the arts, sciences, music, mathematics–using what I found from studying how creators speaking about how they create.

SK-M: In Understanding Those Who Create you talked about emphasizing creativity in domains. Also the issue you just talked about –validation– not being recognized or acknowledged by researchers.

JP: Well I mean I am just a little pimple on the creativity skin, a crater in the creativity firmament. That I have been taken seriously is a shock to me. Look. I’m a woman who went to state universities, coming up with my own thoughts about things without even having a PhD in creativity, nor in psychology. My PhD is in educational administration. I had completed my PhD before I got into the field of the education of the gifted and talented. I was doing my dissertation by the time I started in gifted ed. I really have no guru, no master. Mary Meeker picked me as an advanced trainer for the Structure of the Intellect and I did that for many years. I consider her a mentor, but we are really far apart in thought about intelligence. Now I am not a Structure of the Intellect person at all any more. But I think I have combined my literary background with my Master’s in Guidance and Counseling. I have studied some psychology. You know my thought has developed in an idiosyncratic way where I haven’t had to be influenced by my professors by a certain school of creativity.

SK-M: It seems with your degrees, all that you do in different content areas you bring that altogether for yourself.

JP: Yeah. I make my own connection based on study, reading, thinking, insight. I remember my insight about talent development–“it’s personality!” “It’s personality that influences or determines how one develops one’s talent,” I said to myself while driving on I-80 to visit my children, while thinking about the IPAR studies. My editor at Merrill Publishing had told me that a good way to wrap up the textbook, Talented Children and Adults, would be to make a theory, and so I walked around thinking, synthesizing, and trying to make sense of what I hard been studying, writing, about, and reading for the 900 pages of that tome. “What have I learned? “I asked myself. “What have I learned?” Then I realized that the cognitive is a minimum capacity and not a maximum capacity for each domain. That domains differ in what intellectual capacity is needed to do the work of that domain. That came from Simonton and from a workshop on creativity that I attended when I was in a small group task force. The insights kept coming and I drew on my reading and study and formulated the first iteration of the Piirto Pyramid. The Sun of Chance came from Tannenbaum’s model; The Sun of Gender came from my long work and interest in women’s studies.

Then I know I am not a great theoretician or anything like that. Yet I think what I have developed holds in the creativity and giftedness area. I think that my thought will be around. It is in the books. I have been very fortunate to be able to write the books. People can take a look at my work. The 3rd edition of Understanding Those Who Create, renamed Understanding Creativity, is based on the Piirto Pyramid; every chapter is organized by genes, personality, the cognitive intelligence, what this talent in the domain mean, and the five environmental suns.

SK-M: Along with that you had talked about what influenced your accomplishments the most and you talked about teaching and organizing material as a subject to teach it and how that really helped you grow in the area like teaching qualitative research, teaching about the gifted and talented. Do you see teaching something as a big influence?

JP: Well absolutely. It is an old adage that when you have to teach something you have to learn it. I was a French minor in undergraduate school and got good grades. I had 25 hours of French and we were living in Kent and I had been a graduate assistant in the English Department and my husband was an undergraduate freshman student. We did not have any money so I decided to go for a teaching job even though I had quit studying education in my senior year of college because professors had told me I should go on and get a PhD. Therefore, I didn’t student teach but I had all the other courses in education for a certificate. In 1965-1966, our last year at Kent State, I got a teaching job in a little farm town near Kent, teaching English, French, and journalism. I was sweating that French because they told me I was to teach French II and advanced French. I studied and I prepared and walked into that class scared and guess what? Those kids knew no French. They had distracted their elderly teacher, asking her to tell them stories about her trips to France, and they knew no grammar. They didn’t know how a French sentence was put together. They had no vocabulary.

SK-M: You said you had to take it back to French I.

JP: Yeah.

SK-M: For the vocabulary and grammar.

JP: Right. I learned more than they did. It really solidified my French even though my friend Christopher who was a French teacher said “votre francais est sauvage.” My French is savage. When I go to Paris, I can read the newspapers, but I can’t converse well.

SK-M: And that is the songwriter Christopher. You had talked about your friends also as influences.

JP: You are blessed with friends throughout your life. I just think when I was a graduate student at Kent State in my 20’s, my friend Shirley and I stayed in touch for years. I just really admired her brain and when I first started writing poetry, she would critique it for me and not just say how nice.

Then I had at Northern Michigan University when I was a professor there in English, I had an office mate. Kay. She and I are still wonderful friends. We were pregnant professors together. We are book friends and I think you don’t find many book friends in your life so you should always keep them. Kay and I are novel friends. We read novels and talk about them together –”have you read this, have you read that.”

My friend Christopher is a book friend in the psychology area. Depth Psychology and dreams.

You know, people who read are very few and far between. I mean really read. Who are really readers? When you find somebody who reads at the depth and the level that you do you keep them. You know they are always important to you.

Michael Piechowski, in reading Understanding Those Who Create –the first edition– was so tender in critiquing everything. I had no idea what I was doing writing a book. He really helped me. He has two PhDs, one in microbiology and one in counseling psychology. He is one erudite person. Like all people who show their work to others, I wanted people to say, “Oh this is wonderful,” and he wouldn’t say that. I had to think about how you always get defensive about criticism and I had to think about what he said. And I did. Christopher and he both read the manuscript for “My Teeming Brain”, and that is wonderful. I don’t have my literary friends read my scholarly work. Kay did read one of the manuscripts —Understanding Those Who Create I think. Rena read it too. Rena is very critical. An old friend I trust.

The big textbook, Talented Children and Adults, nobody read but the editor. That book is the accomplishment, along with the publication of the literary novel, I am most proud of, because I read everything in gifted education to write it. I began by reading other people’s textbooks and I found I couldn’t read them. They were so dull. I remember thinking, “What will I do? I can I never sustain a big long book like this with this kind of model.” I mean I am not criticizing their monumental work in writing those textbooks. The other textbooks just didn’t inspire me. Thus, what I did was I just decided that I would write my own way, and I want back to Plato.

You look at the first edition of Talented Children and Adults and you can see that the style departs a little bit from the regular textbooks. I begin each chapter with a topical scenario, for example, and I try to write in a conversational tone. It came out and did well, and then when they asked me to do a 2nd edition of Talented Children and Adults I said, “Why do you want a new edition? I said it all in the first one.” My editor said, “Well you know we are a big publishing company and we usuallyclike 4 or 5 years in between editions–it came out in ’94 so we would like a second in ’99.” I said, “All right. I will do it.”

And then I found that as I researched and wrote a 2nd edition, I took her advice that a textbook writer should do 25 percent of revision in each edition. I was able to include all the Javits grants and a lot of other new materials in the second edition. Those big books—900-page manuscripts–are major, major for a single author like me to write on her own. The publishers had blind reviewers to give perspectives, but I am very proud that I could keep all of those references within my mind and make them coherent.

In Talented Children and Adults, I started a new topic for every one of the 15 chapters. Fifteen chapters for fifteen weeks of a semester. The first chapter is about the nature and needs of the gifted. The 2nd chapter is about developing programs. The 3rd is assessment. Then there is the educational and psychological development of young gifted children, elementary gifted children, high school children, adults, and then I wrote about guidance and counseling which is now called social and emotional needs, but I like the old term because if you get the guidance you probably don’t need the counseling. I then wrote a chapter about minorities and twice- exceptional talented children.

Then I wrote 2 chapters on curriculum. I had started hanging around the curriculum theorists in education. Gifted education people are quite conservative. They are just really mostly Tyler-driven—essentialist and positivistic– and so I asked myself “What are the current best thinkers in curriculum and education thinking; what are the radicals thinking?” That opened up a whole new area for my writing and thinking and so I attended conferences and submitted journal articles and I am now part of that group too and they influence me. My friend, the postmodern curriculum theorist, Patrick Slattery, has influenced me a lot. If you want to grow you just have to find out who is doing the thinking.

SK-M: You said that you often search for new thinkers.

JP: Yes absolutely.

SK-M: Look for people who are doing.

JP: But the other thing is I revisit the main thinkers. I always try to see what the main thinkers are thinking now. I just emailed Dean Simonton after I read the Darwin book and I said, “You are it Dean. You are it. You are the creativity thinker of the ages.” Dean Keith Simonton is doing it. Instead of us saying, “Well, Simonton did his work with genius and that’s it.” As if his brain is dead and he is never going to do any new work. He is always doing new work, and so are most of the other thinkers. At the state and national conferences, I always go to see the famous thinkers‘ sessions to see what they’re thinking now.

SK-M: You had talked about gaining confidence. You talked about it starting writing at age 30. About having the first poems you submitted accepted and that this really helped you later continue to accept rejection. Can you say a little bit more about how you deal with that? I know you said you had a drawer full of writing which I think is just such a great, kind of a metaphor there.

JP: Drawers. Drawers I have many drawers, file drawers full of my writings. I dust them off and send them off and sometimes I don’t because it is much easier to get published in the psychology and education world then it is in the literary world. I treasure all of my literary publications but for every one that gets published, there have been a lot of rejection letters, form letters that come. I don’t save them anymore. I throw them away– the letters. Now they don’t send back the manuscripts. They recycle them and you don’t send all this return postage – you just have postage one way. Then you send a self-addressed stamped envelope, you put the stamp on it, and they get the privilege of telling you –on your own dime –that it is not good enough for their magazine. It’s getting to be more and more online now, electronic.

SK-M: You had said in the literary world it is either accepted or rejected where in the academic world it is revised.

JP: That is right. You have a chance to revise it. Right now, I am working on a review of a manuscript for Educational Researcher. When you review a manuscript, it is “Reject.” “Accept with revision.” “Suggest another journal for it.” It is a kinder way of dealing with creative work. And scholarly work is very creative. In the literary world, if you revised it, they wouldn’t consider it. It is as if what you submit is finished, and they will read it, and then they will reject it, and a lot of the rejection is done by graduate students who are getting MFAs in creative writing and so you have to consider that they are young. You have to consider that they haven’t read as much as you have. There is a stylistic thing there they probably go for. So it is hard. It’s hard. Many hearts are broken from rejections by graduate student manuscript readers in the literary world.

SK-M: I wonder what your reaction was to critics in professional fields you worked in or how it they have influenced you.

JP: Well of course everybody is defensive when you get the critique back. But then you listen to it. And revise. And resubmit. If you don’t then you wouldn’t have anything published. Right now, I just sent back a revision of a study of the values of talented adolescents before and after September 11. I had to revise it a lot and then I decided to change the study. I asked the editor. I said, “I am going to change this. Who cares about small differences between males and females? Who cares that I found that the groups were similar? I am just going to say these kids ranked national security 18th –the lowest– and I went ahead and focused on their comments.” She said maybe she should send it to new reviewers.

I said you can do what you want but I think this is the way to go because I have these statistical people advising me to do all these elegant things and well I should do a Q sort and I should do a factor analysis and I said “I don’t want to. I don’t want to. That is the point. The point isn’t the difference between the boys and girls and since there was no difference between the groups. The point is why are these kids choosing Salvation first and National Security last?” So I did a big whole revision. I had gotten the refusal a couple months ago. Then I revisited it. When you let it sit for a month or two or a few weeks and then you can go back and say, “How can I change this according to their comments and suggestions?” I went back and saw what the study was really about. Not gender differences but values.

For example, Christopher and I had written the first depth psychology article. Did I send you that article?

SK-M: No.

JP: Well this article is in gifted education, which is influenced by all academic psychology. Sometimes educational psychology is called pseudo-science because it’s very difficult to have control groups with human children. We argued–we said, “Listen. This is a big field in psychology –Depth Psychology –and it has not even been dealt with in gifted education even though we are talking about people who have the highest levels of ability and they can apprehend this difficult field.”

“In the literary field and in the humanities, depth psychology is really big, and you are not dealing with that.” We wrote and sent an article, revised it, sent it back, and the editor lost our revision. She found it and then she had to send it to new reviewers and she told me they were going to reject it because it is not clear enough. I said to the editor that it is as clear as depth psychology can be. We revised again. It is about persistence, persistence, persistence, persistence. Now we finally are going to get this in that journal. The journal responded, and we revised: “All right, you want us to do this, you want us to do that. We will respond to all of these things.” It is a long process. And many people are faint-hearted, and they won’t continue the process. They get their feelings hurt and quit.

SK-M: Persistence is a quality absolutely. Do you feel that that process always or sometimes pushes you to do better work?

JP: Absolutely. Absolutely. I almost always feel that revision makes it better. I wish that literary magazines would say, “You know, can we work with you on revising this? We are [after all] editors.” That would be helpful.

I have only had one article that I submitted to a scholarly journal be accepted without revision and that was the poetry article in the International Journal for Qualitative Research. [Piirto, J. (2002). The question of quality and qualifications: Writing inferior poems as qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 15 (4), 431-445.]

SK-M: It is very unusual that it would just be accepted with no revisions.

JP: Right. And so that is a matter of pride because what the editors told me was how unusual that is at the International Journal. They said the editors could find nothing wrong with it. People are telling me it is becoming a classic. It only came out in November and it has been referenced already in Educational Researcher. I was speaking in Oklahoma a few weeks ago, and somebody wanted to sit next to me because of that article.

SK-M: Wow.

JP: She was a qualitative research professor, and she thought I must have some magic or something.

SK-M: You had talked about risk-taking and I love your stories of travel with your mom and the new jobs, the moving, the teaching in the American schools. You talked about it being part of your makeup and I just wondered do you seek risks out to take or do you feel like you just rise to the challenge when they are presented, or both?

JP: Well I choose them too. People have told me they would never dare to pick up and move to New York City without even having a place to live. I just thought it would be fun. Right now, I am planning to go to Australia, and I am going to travel alone for 2 weeks before the World Conference in Adelaide. I have got most of it planned, but I don’t really know many 60-year-old women who would just go alone and drive the other side of the road. Rent a car and go and go on a canoe trip with a tour and swim beneath a waterfall. It sounds like fun to me.

SK-M: You said it upped the intensity of the experience. It helps you write.

JP: Well yeah. I’m sure I’ll write about it. I guess I am not as scared as some people. I can say that sounds like fun and then people say to me, “I would never do that.” I think that comes from my early childhood of being a tomboy and that free play in the woods, that sense of freedom of roaming through the woods in your imagination, being a jungle girl, being a cowgirl, being Nyoka, Queen of the Jungle with the great fun of imagination. That is possible when you live in a neighborhood where you don’t have to worry. A neighborhood with woods and bluffs. You could disappear all day long. You would hear in the distance your mother calling you for lunch but if you didn’t come home, she wasn’t worried—at least our mother wasn’t.

Kids don’t have that today unless they do live in a rural area. I was a tomboy. I have a great picture of me with my cousin from the city and she is in her little dress and looking very demure and then me with my ratty jeans and my t-shirt and my boyish Prince Valiant haircut. I love that picture of me as a 9-year-old girl.

I just love it. Roaming around the neighborhood. Going outside early in the morning and joining the neighborhood baseball game. My sister said, “You play baseball all summer.” I said, “I know. I love baseball.” One of my girlfriends and I would play baseball and the boys would let us play. It was just great. I got chosen 2nd or 3rd of the girls. I couldn’t run but I could hit. So those neighborhood days were absolutely precious and formative.

SK-M: It was like a sense of adventure.

JP; Yeah. I just I think that takes place in my travel. My lack of loneliness. Now I’m 60, I should be an old, timid, lady but there are more things to do. I really don’t feel old at all and I don’t feel scared. Well, I am scared sometimes driving at night on the interstate coming back from teaching because of the black ice slippery roads and splashing semis.

SK-M: You said you had always grown up with music. Cousins, aunts, uncles, grandmother. That was part of your love of art.

JP: Yes. My mother is an amateur artist and every time we would travel, we would go to museums. Even though we were rural, we always visited museums.

Our family would sing around the piano. Everybody would sing and it was just absolutely a lot of fun. Every Saturday night we all went to Grandma’s and my aunts, played. We would sing.

SK-M: You said that your parents did not have a clue about getting into competitive college, but your father and your family had really encouraged you and said you were smart.

JP: My father. When my father was with all three of us girls, he was very much an advocate and so he would say, “You’re smart, go to the University of Michigan and be a doctor. You want to be a teacher, A teacher? Go for the money. Go to the University of Michigan and be a doctor!”

Of course, I was influenced by my peers and I knew there were only 3 or 4 professions for a girl who was going to college. You know –teacher, nurse, secretary– and so I thought, which one of these would I like? Teacher. Ok I guess I will be a teacher. My father would get mad at me. But he had no clue about how to get me 500 miles away to the University of Michigan. I didn’t know why I didn’t know how to get there. My high school had no counselor. I didn’t even take the SAT because I was babysitting that weekend. My teachers didn’t advise me. All I thought about was the cost. Money, money, money. Now, when I advise people, I tell them admission is the main thing. Try to get in and the money probably follows. You have to try.

SK-M: You said your family would support you in anything that you wanted to be.

JP: Sure. I mean you had to consider the restrictions of society, though.

SK-M: You really felt there were just a few ways to go.

JP: Well that is typical. Any girl my age knew exactly what her profession should be. Teacher, nurse or secretary, airline stewardess. That what all the women in our class became. Teacher, nurse, secretary, airline stewardess. Oh. And social worker.

SK-M: Then lots of times in your life you thought you were going one place and ended up taking another job or going in a different direction. You said you gave up your teaching job at Northern Michigan to move to South Dakota at 30. Was that an easy decision.

JP: Well my husband had finished his master’s in regional planning. And I loved being a college professor. That was my ideal job. I loved it. Then he had received a master’s in regional planning and then he was looking around for jobs and he got this job offer in South Dakota. I had been told I had only one more year to teach at Northern because I had been there five years and I was informed that the 6th year would be my last, because I hadn’t gone for a PhD. If I would go for a PhD in English then maybe I could get another one-year contract, but it was now or never. I was on a tenure track.

One of the men who had come in with me had the same credentials. They were being more lenient with him, saying to him that if he would go to the University of Michigan and work on a PhD, they would keep him. I remember thinking that is not fair. That is not fair. My teaching evaluations are great. Of course, it was absolutely blatant discrimination and he did go down to the University of Michigan and work on his PhD. I was told, “Well, you’ll be following your husband now he’s graduating, and so . . . ” Twenty years later, he still hadn’t finished but he got tenure and he never went back to finish his doctorate. A couple of other men in the English Department did the same thing. They didn’t get a PhD, they fooled the administration and got tenure. I knew that I was not going to be treated fairly, like men. Like men. But it gave me the impetus to get a PhD. The power of negative evaluation in instituting personal growth.

When we moved to South Dakota, I went into a depression. I was taking naps all the time because I missed teaching. When you teach, you can get all of your thoughts out. Whatever you are thinking about no matter what subject you are teaching. Somehow you can get you philosophical thoughts out and I was not able to do that. This was one precipitant for my coding my thoughts into metaphors, poems, creative writing.

I started substitute teaching. I couldn’t get a teaching job, a high school teaching job because I had a master’s degree and 6 years of experience so I was too expensive and they wouldn’t hire me. But then I decided to retrain and to try to get a job which required an entry level master’s and that was to study to be a guidance counselor. When I did that second master’s at South Dakota State University, I got a job. Two jobs. I got one at a small farm school, and then I got one in Brookings, which is a college town. I spent a lot of my life commuting over an hour one way.

Then we moved back to Ohio. My husband got a job with his father as a salesman. I said I am going to go on for a PhD. I am never going to get caught in this thing again. Bowling Green State University offered the PhD in educational administration and I said to myself, “Oh I could do that. I can run a school as well as any coach.” So I applied and all of my professors in counseling said, “Oh Jane, you should go into ed psych.” And my literary friends said, “Jane, you should go into English.” Then I took a look at the required courses in those programs and said you know I don’t want to be a therapist because I would be too impatient and I know I don’t want to critique literary fiction. I want to write literature. I don’t want to do composition and rhetoric theory either. It just didn’t interest me.

SK-M: You said you don’t want to grade those English 101 papers.

JP: Right. Thirty years of how I hate my roommate. Just kidding. But those themes are deadly. Now I read papers submitted by working, mature adults who are educators. So I just went into educational administration. It was a great choice. It was 1974.

SK-M: You said there were 7 women in that program.

JP: The program had been under been civil rights watch because they only had men studying educational administration, so they had to admit a lot of women. We had a little women’s group while I was in the doctoral program. Only one of us was invited to join Kappa Delta Pi, an administration professional organization. That’s when I vowed I would never join it. And I haven’t. Though now it’s mostly women, I hear.

SK-M: Do you feel like people in the program were really those who became colleagues and supported each other?

JP: No they didn’t. I clearly remember it was very intense when you’re in the doctoral program. But as soon as I finished in 1977, I started hanging around people around town who were more normally my type, the literary writers and other artistic types in Bowling Green and in the city of Toledo. And some of my best friends are still those people.

SK-M: You had said that really you like to be around people who read at the same depth that you do.

JP: Yes.

SK-M: You mentioned finances as a factor in several of your educational and job choices, but you said finances were not a negative influence. I wondered if you could just tell me a little about that.

JP: Well they were a negative influence. Who knows what would have happened if my family had more money? I come from the working class. My father worked as a skilled worker, a welder, for a mining company. The whole town was really run by this mining company. I went to a Finnish American junior college –Suomi College–because I wanted to imitate my friend’s older sister, who played the piano and I wanted to play like her, be like her. I went there and it was a college for someone with my ethnic roots and protestant religious denomination, but the academic challenge was nil, so I started casting about and I got accepted to Augsburg college, another Lutheran college, in Minneapolis. Well, it was great; Minneapolis was great and my courses were great because I was really, really challenged. But the economy sunk and my father was moved from the company’s shop as a welder, out into the wilderness, to work at a diamond drill exploring for beds of iron ore. It was a union thing, so they laid off the lowest in seniority and he got moved. He was demoted to a 6, which is what a diamond drill operator is.

He didn’t tell me in so many words, but I knew that it was a problem. I knew that if I went home and lived at home, they would only have to pay tuition and then I could commute to college with my high school friends. So that is what I did. I transferred back home to go to Northern Michigan University and I commuted for the last 2 1/2 years of my undergraduate degree. I didn’t live in the dorm. Northern was fine. I had wonderful professors who were fantastic, but I was also not in a different culture. I was in the culture of home. But my parents were able to afford it without sacrifice.

SK-M: It sounds obvious but I don’t know that everybody does like a challenge, you know, in their studies.

JP: Absolutely, I admired my professors. I still do admire intellect. I don’t like the same old stuff. I need to think.

SK-M: You are drawn to new things.

Old things. People making old things clearer. I would like to go and get another PhD in mythology. That just interfaces with my poetry.

You had mentioned a couple of things in the future– clinical psychology, the creative writing program, and not to retire.

JP: At least right now, I don’t see myself retiring. I don’t know what will happen when I’m 65. That will be 4 years from now. I have to check and see what my retirement savings are. See if I have enough to do it. But I foresee going until I am 70 if everything is ok. [I retired at 75.]

SK-M: When you retire do you see yourself writing?

JP: Yeah. I always write. Maybe the great Upper Peninsula novel. Or I don’t know. Maybe it might be non-fiction. I am real interested in the interface between my home town and Cleveland, Ohio, and I think my home town was a really rough and ready town with all of the streets of taverns, people from all over the world. Many ethnic groups. We grew up in the north and we didn’t have many African Americans. We did not know who our Native Americans were. The Indians just blended in with everyone. I was surprised to find out, recently, how many of our neighbors were Anishinabe tribe members. I even babysat for one family, who never told me and I never asked.

But we did have European ethnic groups of all sorts. We went to school with people with lots of different last names. Italians, Norwegians, Swedes, Cornish, Polish, French Canadian, and many Finns. When I go there, I just go to the library and take my computer and I work through the years in the newspaper on microfiche. That local history is interesting to me. Nobody has really done a biography of the Mather family from Cleveland, who owned the company and who were a major influence in the state of Ohio and a major influence in my home town of Ishpeming. So that fascinates me.

SK-M: I just have one or two other questions. I talked about compromises and you said that no real compromises except for the ones that any professional woman might make when she’s a wife and raising children– the double bind of raising children and work affected you. Would you say that that was big? That had a lot of effect on your productivity?

JP: Well, picture a young 21-year-old who has a fellowship –full PhD fellowship –to Michigan State University, and who had refused one to UC Berkeley. She was a Woodrow Wilson finalist alternate who got pregnant from a guy who had no college and they have a baby. She just turned 22 and has written to Michigan State University late in August and refused; she said “I can’t do this. My life has had some other things happen.” So there went the full fellowship. (I did then get one from Kent State which was nearby.) We were young people in our early twenties, raising children. We planned our 2nd child five years later, while I was teaching at Northern Michigan University, putting my husband through his undergraduate and his master’s degree with the help of his GI Bill benefits. Thank god I had a bachelor’s degree. If I did not have a bachelor’s degree by the time, I got pregnant, things would have been different.

I was able to teach. I was able to go to graduate school. I followed my husband to South Dakota even though it looked like it would derail my career towards a PhD in English. We lived in Watertown, where his job was, far from a possible university where I could get a PhD. But it turned out to be a wonderful experience. I love South Dakota. The 3-years there was absolutely fantastic. I got involved in a whole new field, of guidance and counseling. Women often move with the husband’s job –my women students understand this–and then new things open up. You are frustrated because you don’t have a straight trajectory towards what your goals are but as you take those side roads there are very interesting things that happen.

SK-M: That is interesting. Yes that makes sense.

I love the way you talk about Numinosity. You talk about rising into large feast of vision in one’s 50s and 60s.

I haven’t reread that essay in a long time. I’ll insert a few paragraphs from it.

THE NUMINOSITY OF FIFTY-NINE

An Essay by Jane Piirto

I ran across a new word, the word numinous. I suppose I had seen it before, but I never really thought about it, nor looked it up. Numinous. The awareness and experience of the holy, the sense of grace, of the sacred in life. As I begin to write this a soft snow flutters outside the window, huge white flakes stuck together, drifting down. It was my birthday. I was fifty-nine years old.

Nine is the months of gestation before a person is born, the number where flesh is born, a number of wholeness. A circle has 360 degrees, 3 + 6 + 0 = 9. Cats have nine lives, and superstition has it that one can cure an itch by whirling a black cat around the head three times, and then putting on an ointment made from nine roasted barleycorns and nine drops of blood from its tail. The ointment must be put on with a gold wedding ring, another symbol of completeness. Christ died at the ninth hour after he finished his life on earth. He blessed nine types of people in the Sermon on the Mount, the poor in spirit, the meek, those who mourn, those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, the merciful, the pure in heart, the peacemakers, those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, those who are reviled. I guess I’m one of those who is poor in spirit.

I remember my lucky birthday, my 19th, on December 19, 1960, when I was a sophomore in college and my parents told me I had to leave the private school I was attending in Minneapolis to come back home and commute to the state college, because the recession had put my father on the diamond drills and they couldn’t afford to send me; and my 39th, when I was in the throes of divorce after a long marriage of 18 years. My 49th, spent where I live now, here in Ohio; my 29th, spent in Marquette, teaching at Northern Michigan University, bring no memories. The 9th, 19th, 29th, 39th, 49th, and now 59th birthdays are more frightening and provoke more thought than the actual 30, 40, 50, –and next year – 60! Time to take stock.

This was the year of the search for the sacred, for numinosity. In August and September, 2000, my mother and I drove 8,000 miles, to California and back, with a goal to visit sacred natural sites of the U.S. West. We visited my sister and her family for awhile; I attended a depth psychology conference on the experience of the holy, its numinosity, and this is where I began my meditation on the experience and on the word. We experience the holy psychologically in many other ways than in our conventional religions and worship services. We experience the holy through creativity, through nature, through relationships, through the body, through psychotherapy. Common to the experience of the numinous is a feeling of transcendence, along with a feeling of insignificance and awe in the face of the divine. We all know this, of course, but it is good to hear the thoughts of intellectuals about the subject, and I enjoyed sitting there in the hills of Santa Barbara taking it all in.

And then the daughter drove and mother and daughter wended our way back — through Yosemite, King’s Canyon, Sequoia, Zion, Monument Valley, Mesa Verde, Colorado National Monument, to see my son in Denver, to see my sister in Sturgis, SD, with side trips to Devil’s Tower, Bear Butte, and the Black Hills. Driving to Ishpeming, Michigan from Sturgis, South Dakota in one day, 1,100 miles, with my Honda CR-V hitting an average of 90 on highway 90 (those nines again!) was some kind of record for me.

We saw the amber waves in the plains of farm fields, vast corn stretching to Nebraska along the Platte River, sand bars in meandering streams; we experienced beating sun, long trains, small towns, high plains wheat, the beacons of feed silos, tan ranges, dots of black cows on wide hills, a feeling of being West; we saw the spacious skies as we drove across monotonous salt deserts, flat and glaring like shimmering water, we saw foothills of tall humps of woolly-sage- backed hillocks, heard the merry beckoning of bells in a roadside casino, the tumble of coins falling into chrome boxes; afterwards, we smelled of stale smoke. We saw the purple mountains and we even met tired fire fighters from forest fires in Wyoming one night in a diner.

We drove and drove — into the ravishing parks of the U.S. with their waterfalls tumbling, green lakes with blue reflections. Words cannot describe the colors — granite knobs and slabs upthrust by geologic action millions of years ago — spires of trees pointing to bald tops of gray rock — winding through forests of ponderosa and sequoia — mile after mile of unspoiled beauty so remote it cannot be reached except with great effort. Remoteness carries a sort of epiphany — reserved, aloof, always in the background, part of the world heritage, a context hidden from front view, an impression, a conviction of presence — stillness not present but always present, remoteness accessible enough.

Driving there is becoming obsolete; flying is becoming the American way. Edward Abbey aside, I love my car and driving. I love to observe the passing scene through windshields. . . .

SK-M: Thanks for talking about your journey and all the things that happened to you early on.

JP: My kids are coming tomorrow for a 90th birthday party of their grandmother. I am getting the house ready. I’ll spend 3 or 4 days with them over the weekend. My son is from Colorado and my daughter is in New Jersey. I live alone and so I am free. I mean essentially free. I’m economically free. I am socially free. I am psychologically free.

I have a teaching motto. “What is the image?” My friend asks students in his creativity classes what is the first picture book that you made your parents read over and over because that is before television grabbed you and that is an image gives you insight into your deeper self. Then he asks what is the first song that you remember that you needed to play over and over and would always remember. Again, that is a clue to your inner self. My first song was Don’t Fence Me In. “Give me land, Lots of land, ‘neath the starry skies above. Don’t fence me in.” And it’s still true. That’s what you should title my section.

SK-M: Isn’t that something? Well that says a lot doesn’t it.

JP; I am very fortunate.

SK-M: So you feel much more a sense of freedom now than in your younger years.

JP: Well yes. I don’t have to get a babysitter! I didn’t live alone until I was in my mid-forties. As a matter of fact, my 2nd novel, The Arrest, is about a woman whose husband gets a vasectomy without telling her and she is so bummed out about it that she has an affair with this major drug dealer and she met on an island in Florida. It’s a road novel where she is going around the country with this baby because she gets pregnant by him. She is driving around the country with a baby all the time. So there something in that as well. You know. Having children is a transforming experience and is the most wonderful experience but it is an also an experience that you have a lot of responsibility early. [Novel is available on Kindle and Nook.]

SK-M: That is just wonderful. This is good data. It is wonderful to talk to you. Well Thank you.

JP: You’re welcome. What do you plan to do with this?

SK-M: Well I am going to do 12 case studies and then take a look at them. You know write about these case studies.

JP: Is this your dissertation?

SK-M: This is a dissertation.

Doctoral Dissertation entitled A Qualitative Study of Women of Extraordinary Women of Creative Accomplishment by Susan Keller-Mathers at Argosy University/ Sarasota. Completed and defended in 2004.

,