Female Teacher/Researcher

Female teacher/researcher: My work in talent development education and in creativity education.

Female Teacher/Researcher: My Work in Talent Development Education and in Creativity Education

Jane Piirto, Ph.D.

Trustees’ Distinguished Professor Emerita

Ashland University

Cite as: Piirto, J. (2021). Female teacher/researcher: My work in talent development education and in creativity education. In D. Y. Dai & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), Scientific inquiry into human potential: Historical and contemporary perspectives across disciplines (pp. 142-154). New York, NY: Routledge.

This edited book contains fascinating autobiographical essays by Philip K. Ackerman, Stephen J. Ceci, David Yun Dai, David Henry Feldman, Richard Florida, Howard Gardner, David C. Geary, Judith Gluck, Fernand Gobet, Jane Piirto, Sally M. Reis, Joseph S. Renzulli, Nancy M. Robinson, Mark A. Runco, Larisa Shavinina, Dean Keith Simonton, Robert J. Sternberg, Rena F. Subotnik, Ellen Winner, Frank C. Worrell.

Context for My Work

My story is unusual for this anthology. The context for my work is the field of the education of the gifted and talented. I entered this field at the age of 36. I am a retired professor of education and was the Director of Talent Development Education at Ashland University, leading the endorsement and Master of Education programs, whereby teachers obtained state approval to teach identified gifted and talented students. I was in the field from 1977 to 2017—40 years. Before being the lead professor in charge of the gifted endorsement courses at my institution, I worked for 13 years as a high school teacher, college instructor of literature and writing, coordinator of programs at regional education offices, and principal of the oldest school for gifted children in New York City, the Hunter College Elementary School. My shadow self was and is as a published and award-winning poet and novelist.

Influence One

The Federal Report, National Excellence, came out in 1993, just as I was writing my synoptic textbook. Talented Children and Adults: Their Development and Education, a basic textbook under contract with Merrill, for people studying the education of the gifted and talented. This report famously encountered the use of the term “gifted” and suggested using the term “outstanding talent.” The most successful basic textbook author at that time was Barbara Clark, and her book had gone into several editions. My editor at Merrill hoped that my book would do the same. With this influential report, I engaged in a search and replace action for my manuscript and began to name the strengths by domain. I replaced the term “gifted” with “academic talent,” “high IQ,” “mathematical talent,” “verbal talent,” “spatial talent,” and the like. I changed the title of the book from “Gifted Children and Adults” to Talented Children and Adults: Their Development and Education This report and its suggestion that we drop the term “gifted” was profoundly influential for my work, as it made me think about talent in domains, and to discount the influence of IQ assessment for identifying such.

Influence Two

Another influence in my thinking was my eight years of work with alternative assessment in our field. Mary Meeker (1969) modified the work of J.P. Guilford using 26 of his 120 tests to assess school children. Meeker was my first real mentor in the field. Since I entered the field while doing my Ph.D. in another field, I had no relevant advisers. In 1977, I attended a two-day seminar in Columbus, Ohio, given by Meeker, teaching us to administer and interpret the Structure of Intellect Learning Abilities Test (SOI-LA). I had a background in assessment from my studies to become a guidance counselor, and this test attracted me, because it purported to focus on strengths and to minimize socio-economic differences. It de-emphasized the importance of IQ, and offered diagnosis and remediation for academic weaknesses.

I became an advanced trainer. I conducted many workshops throughout the country, flying to school districts, taking up the slack for Meeker or her husband Robert. I peddled the use of the test with identified gifted populations. I even conducted SOI assessment workshops in my home and at a local Bowling Green motel conference room. Many of my colleagues in gifted education in Ohio and Michigan wanted to find alternative means of finding smart people, means that were not IQ tests. I said I had the answer: the SOI!

But when I used the SOI Learning Abilities Test to test some students in the Hunter College Elementary School who were judged by teachers to be having academic difficulties, the results told us none of the students needed remediation because they were gifted. I realized that the SOI test ceilings were too low for high IQ students. I had been out nationwide in the community of educators of the gifted and talented, propounding an instrument that was not suitable for the population for which it was being touted. Carroll (1993) called Guilford’s research methodology “idiosyncratic” and discounted it, saying that it could not be replicated, and the Mental Measurements Yearbook’s test evaluation reviews were less than positive. Later, I wrote a biographical study of Meeker for a book about pioneers in our field. I sympathize with the work she tried to do. The pressure on test-makers in validating their work must be extreme.

Influence Three

In creating my research line, I had to figure out how to work alone, without graduate-student help, while teaching 12 hours a semester. My graduate students were full-time employed teachers and school administrators, taking courses to add to their credentialing. Who could I do research with? Or on? I had colleagues in the field at other universities and in schools with whom I could collaborate, and I did (pace Diane Montgomery, John Fraas, Barry Oreck, F. Christopher Reynolds, David Feldman, Kari Uusikyla, Susan Keller-Mathers, Karen Micko), but mostly I worked alone. I continued to write and receive grants for Summer Honors Institutes from the State of Ohio, so I had a population upon which I could collect personality assessment data—and I did. I am still sitting on much data.

I had to create a line that engaged me. What would inspire me to have the self-discipline to continue? I like to invent. I like assessment. I like textual analysis and I also am curious about and find pleasure in reading biographical materials. These were the lines I tried to merge.

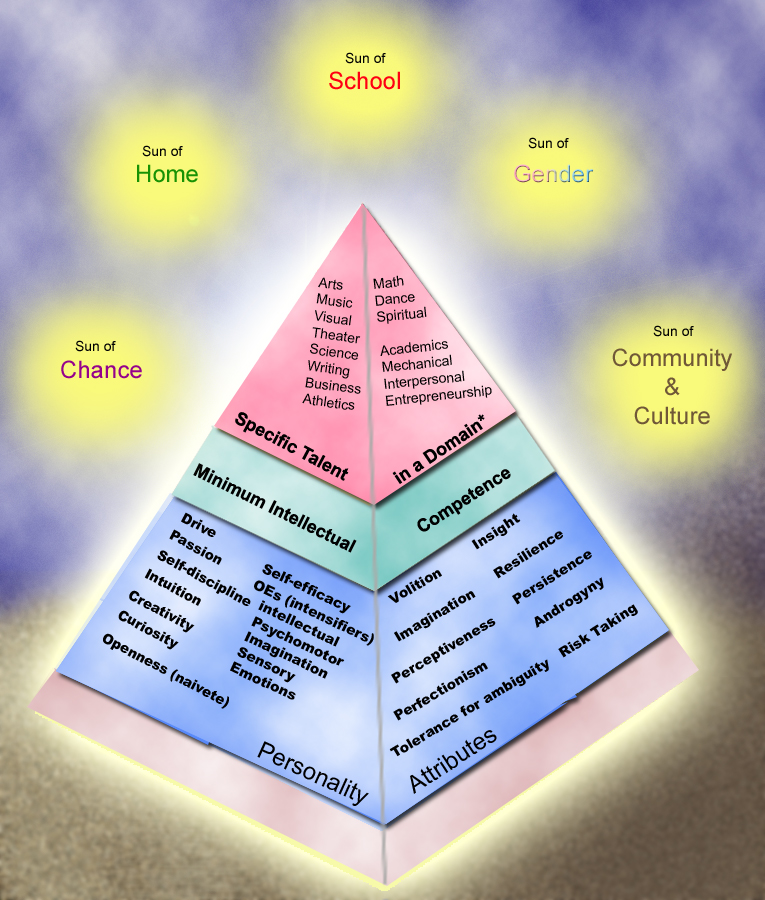

Genesis of the Piirto Pyramid of Talent Development and my work on creativity

As I was writing the textbook (1994, 1999, 2007) under contract for Merrill (later Prentice Hall, Pearson, and then Prufrock), I was also simultaneously reading for and writing a book on creativity under contract for Ohio Psychology Press (later Great Potential Press). It was called Understanding Those Who Create (1992, 1998), and the third edition was renamed Understanding Creativity (2004).

After doing the wide and intense writing and reading for both books, I thought and thought. I wanted to synthesize the material into a theory of talent development. I walked around my life, in a process of incubation, seeking insight, thinking “What does it all mean?” “What does it mean?” I lived alone with my cat—my children were grown and gone– and so the general practices of silence, exercise, and writing ritual were easy companions.

Fortuitously for my simultaneous work on the creative process, as it gave me a story to tell during lectures, I was driving on I-80 through Pennsylvania, the beautiful scenery unfolding, music on the stereo in my car, weather perfect, meditating. It came to me: “It’s personality. It’s not IQ, it’s personality!” I drove to my daughter’s and her husband’s new apartment in Brooklyn and slept in a sleeping bag on their newly carpeted floor, the fumes rising as if this were Delphi, and I were the oracle, the middle-aged woman in the tent sitting on a tripod, sniffing the gas rising from the chasm in the earth, making prophecies.

In the middle of the night, I had a dream of Greek gods shooting arrows. Apollo evoked. I got up and sketched three figures—the god of genetics, the god of personality, the god of cognition, all shooting arrows into an amorphous cloud I called “talent.” This imaginative dream was natural for me, as a former English major with a master’s degree in literature, who had taught Greek mythology to undergraduates in the 1960s. I have been a frequenter of Jungian dream workshops and keep notebooks of my dreams. Creating to me has its mystical side, and as a writer of poems and stories, I embrace this wholeheartedly. My practical side embraces statistical proof, but my inner self listens to emotion, ambiguity, and the enigmatic.

The Piirto Pyramid of Talent Development

When I got back to Ohio, teaching my first class of the semester in 1992, I passed out xeroxed copies of the first chapter of the manuscript, as Merrill was going to field test it on my students. I explained the intuitive drawing of the arrow-shooting gods, emphasizing my insight that talent is developed through force of personality. My students were compliant and nodded their heads. This was their first class in their endorsement sequence and they had never heard of nor did they understand what I was talking about.

But one student stayed after class. She bravely said, “I am a graphic designer. Maybe I can help you with your image. It’s kind of a mess, and confusing. You might want to think of a ziggurat.” I drove the 75 miles north to my home in the college town I lived in, thinking. “Confusing.“ “A mess.” In my mailbox was a magazine I have subscribed to for a long time—Vanity Fair. I like to read the articles and look at the glossy ads. I love the perfume bottles. I poured wine and thumbed through the magazine, with the late news on the television, relaxing after my long day. There in the magazine was a pyramid-shaped form in one of the ads. I tore out the ad and glued it to a piece of paper.

- The Genetic Aspect: Sub-terrestrial. In its first iteration I had the genetic aspect as an environmental Sun, but in the second edition of the book, I moved it where it belongs—beneath. Fascinated by the work of the Minnesota Studies of Twins Raised Apart, and the work of Bouchard and Plomin and the popularity of genetic theory, I thought about the pervasiveness that we do not even know and are now discovering, of genetic influences. This includes genetic manipulation, according to my nephew, who is currently doing his Ph.D. working on CRISPR at the University of California.

- The Emotional Aspect: Personality Attributes

In my literature review for Talented Children and Adults, I accumulated a long list of personality attributes found in various studies. The index for the textbook listed many personality attributes, and in the first edition, I made the list into a chart that summarized their strength among the many studies. Germinal was the Institute for Personality Assessment and Research (IPAR) studies conducted by Barron, MacKinnon, Helson, and others, of practicing writers, architects, inventors, mathematicians, and scientists. The beauty of these studies was that they had comparison groups, conducted much assessment with various instruments, and used Q-sorts and other instruments when they invited the talented people to campus for a weeklong visit. I also was influenced by the proceedings from the Utah creativity conferences in the 1950s and 1960s and by their books published by small publishers and hard to find. Now, with the advent of the Big Five (NEO-PI-R), personality studies can continue with a base instrument and theory. So far, the more current studies have yielded the stronger presence of Openness to Experience among the talented (Kaufman, 2012; Vuyk, Kerr, & Krieshok (2016), which is one of my Five Core Attitudes for the Creative Process in my work on creativity.

- The Cognitive Aspect: Minimum Intellectual Competence

The main influence on this band on the Pyramid of Talent Development was Dean Keith Simonton (1985), who listed the minimum intellectual capacities necessary for achievement in domains. Linda Gottfredson’s work also was influential (Gottfredson, 1993). I was interested in doing away with cutoff scores for inclusion in programs, and although the checklists of Feldhusen and colleagues, Johnsen and colleagues, and Renzulli and colleagues was important, I also knew that the wheel has already been invented, as elite programs in the arts, sciences, mathematics, and literature, social sciences, and physical performance already had sophisticated criteria that they used to evaluate talent.

- The Aspect of Talent in the Domain

The disappointment of strivers who feel called to do work in one domain or another, but who don’t have the mysterious “talent,” is important here. I subscribe to the definition of talent that is in the dictionary: “natural aptitude or skill.” The expertise researchers and some who insist that talent comes after giftedness, have unnecessarily complicated the problem (Ericsson, Krampe, R. & Tesch-Romer, 2003; Gagné, 1985). It’s unfair, but some people are better able to do some things than others. Domains shift according to the Zeitgeist—there is little need for the hunting talent nowadays, and the coding talent has come to the forefront.

- The “Thorn”

However, some of those with talent do not want to do the work of refining and developing that talent, and that is OK. In insisting that the thorn is a psychological impetus, that people can’t not do the work when they are so motivated, I follow Jung and Hillman, among others. The archetypal psychologist James Hillman (1996) described the presence of the daimon in creative lives. In The Soul’s Code, Hillman (1996) described the talents in a way similar to Plato’s and Jung’s: “The talent is only a piece of the image; many are born with musical, mathematical, and mechanical talent, but only when the talent serves the fuller image and is carried by its character do we recognize exceptionality” (p. 45). The thorn is similar to the “call,” but without the religious overtones.

- Environmental Suns

Then I drew the “suns,” the environmental influences on talent development. I had consulted with the American schools in Cairo, Egypt, and had visited the pyramids. I had also noticed how, when you look up at the blue blue sky from the Nile River in a felucca, it seems as if the sky is full of many suns.

6.A.: Sun of Chance: I had used Tannenbaum’s (1983) book, Gifted Children, as a basic text. I admired his starfish model, and especially his inclusion of the influence of chance in the lives of all of us, including the talented. I made Sun of Chance as an environmental influence, influenced by Tannenbaum.

As a working-class daughter of a welder for a mining company in a northern rural town in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, I know how important the Sun of Chance is. When I was the principal in New York City, I received many calls from casting agents and producers wanting to look at our bright children for possible roles in movies, television, and theater. These children had the luck of being born in and living in a center for theatrical activity. The inclusion of the Sun of Chance as an environmental factor was also influenced by the work of Simonton (1984) on proximity and its importance in the development of talent.

The Sun of Chance has clouds over it when a talented adolescent in a rural high school does not get the counseling needed to make a college choice that will enhance a career. In high school, I didn’t even get information on how to sign up for the SAT, and I have never taken the test. My whole entrance into academe as a career had been influenced by my professors at Northern Michigan University nominating me for the editorship of the university student newspaper and for the Woodrow Wilson Graduate Fellowship. I was shocked. I didn’t even know what you had to do to get a Ph.D. and I had never thought of going to graduate school. But I took their word and applied for the fellowship and also to graduate schools. They raised my aspirations with their confidence in a shy commuter student.

6.B.: The Sun of Home. This was apparent as an influence—I was doing heavy reading of biographies for Understanding Those Who Create (1992, 1998), which I had proposed as a book with separate chapters on talented people in domains: visual artists/architects; creative writers; mathematicians/scientists/; musicians/composers; actors/dancers/physical performers. I was finding different themes in the various domains about their family dynamics—for example childhood trauma in writers and rock musicians. I also admired Bloom’s (1985) edited book, which included a lot about the families of the talented people he and his colleagues studied.

6.C: The Sun of School. I am an educator, teaching teachers how to teach talented youth. The Sun of School had been very important in my own life, as with the story above about how my professors influenced my life. My parents were not college graduates and while they were avid supporters of me and my sisters, they did not have the tacit knowledge touted by Sternberg in his model, to advise us about choice of college, though my father, when he was in his cups, would urge me: “You’re smart. A teacher? You want to be a teacher? Go to the University of Michigan and be a doctor. Go for the money.”

6.D.: The Sun of Community and Culture. It became apparent in the biographies, interviews, and memoirs I was reading that all of the people were influenced by their friends and colleagues. The myth of the lonely creator in his garret scribbling or painting alone is just that. In my own artistic life, I was also a member of a community of creative writers—the Toledo Poets Center and other writing groups. My comrades in writing poetry and fiction were dear to me. As soon as I began to write literature and to send out my work, I reached out to others doing the same thing. I wrote fan letters to writers whom I admired. I sent work out to my friends to be critiqued, and I critiqued their work. I gave readings. I attended conferences and workshops. I published my friends in the poetry postcards of my small press, and in chapbooks.

The Sun of Community and Culture was illustrated also in my work as a professional in the community of educators of the gifted and talented. I had lunch with, traveled with, and talked to fellow coordinators of programs for the gifted and talented in both states where I was initially employed as a coordinator—Ohio and Michigan. When I went to New York City, Hunter College hired a young researcher who had attended the school where I was principal, Hunter College Elementary School—Rena Subotnik, who was working on a followup study of her schoolmates of the 1960s. She hired two students to search for addresses in the banged-up old metal boxes in the basement of the school. The kids worked in my office before school. Rena and I became friends, influencing each other. One of her findings in this longitudinal study was surprising. A common trope in our field is that the high IQ students called “gifted” are our “future leaders.” Subotnik, Kassan, Summers, & Wasser (1993) found the opposite. Like the Terman study participants, who had not attended a special school, few, if any of the students who had attended this special school did anything extraordinary in their lives. The researchers said, “Like the Terman group, none of the members of the Hunter group has [yet] achieved the status of a revolutionary thinker” (p. 143). Such innovative and radical thought usually emerges out of obsession and idealism, and the Hunter group expressed wistfulness for lost idealism, but they remained relatively conservative and pleased with their conformity. The belief, or charge, that high-IQ students are our “future leaders,” seems not to have been supported by either the Terman or the Hunter group. This study later led me (Subotnik was also doing separate but parallel paths of thought) to add the “thorn” to the Piirto Pyramid.

I joined professional associations, ran for state and national offices, and was appointed to task forces and the like. Colleagues and I enjoyed discussing our work and we influenced each other. We gradually built up a lot of group trust and I still attend certain conferences just so I can see them annually. When the Piirto Pyramid was first published, in 1994, John Feldhusen of Purdue wrote me a congratulatory letter and published my first article on the Pyramid in a journal issue he was editing. Frank Barron wrote and said “The ‘Pyramid’ is excellent—a compact, eloquent, graphic synthesis.” Franz Monks, of the European Council for High Ability, asked me to speak about the Pyramid at the 1994 meeting. Such attention steadily continued, both nationally and internationally.

6.E: The Sun of Gender. Like other young intellectual women of the late 1960s and early 1970s, I had belonged to consciousness-raising groups. I did my Ph.D. in educational leadership at Bowling Green State University. My interest in women led me to focus on a qualitative historical dissertation called The Female Teacher: Teaching as a “Women’s Profession.” I had read about Catherine Beecher (Sklar, 1973) and her attempt in the nineteenth century to have single women not be spinsters in the attics of their brothers-in-law, but to be out in the communities teaching young children. My own aunts had been female teachers—and they had to quit when they got married—and I dedicated the dissertation to my aunt Lynn, who taught for 40 years.

While working on my dissertation, I came to love archival research. I visited the archives of many of the female seminaries at the numerous small colleges in Ohio, perusing teenage diaries and autograph books, letters to parents, and female seminary charters. My background in literature and my constant, continuous life as a reader of many books led me naturally to qualitative research. This choice to do qualitative research led me to be appointed the qualitative research methodologist for our doctoral program in leadership. In the mid-1990s, while on a visiting professorship at the University of Georgia, a hotbed of qualitative research, I audited courses with prominent qualitative research thinkers—for example, Judith Preiss.

Another influence on gender was more formal. Bowling Green State University began a women’s studies program in 1979 and needed an adjunct professor. I sent my resume; they called it “pretty,” and I began to teach basic women’s studies courses. In 1980 I published my first article about gifted girls in Roeper Review. I also did training for Title IX for the U.S. Office of Education. I have continued to publish and present about gender. My most recent was a chapter on the Sun of Gender in 2019.

The Piirto Pyramid seems to be a rarity in its emphasis on gender as an environmental factor. Noble, Subotnik, and Arnold (1996), Kerr and McKay (2012), and others have models of female talent development but in general models, the environmental influence of gender on both males and females, does not seem to be emphasized.

Impetus

The Piirto Pyramid of Talent Development created the framework around which my work would be organized. I wrote a book on creative writers using the Pyramid as a framework. It is called “My Teeming Brain”: Understanding Creative Writers (Hampton Press, 2002). I organized the second and third editions of both the textbook and the creativity book using the Piirto Pyramid.

In order to confirm the emotional aspect on the Pyramid, I began to assess personality attributes in identified gifted teenagers. We spent an hour and a half twice annually, administering assessments to students who attended the Summer Honors Institute I directed. Over 19 summers, I administered them the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), the High School Personality Questionnaire (HSPQ), the Overexcitabilities Questionnaire I & II (OEQ I & II), the Adjective Checklist (ACL), the BEM Sex-Role Inventory (BEM), the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS), the Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory (BAR-ON EQ-i), and the full Revised NEO Personality Inventory, Adult form (NEO-PI-R).

These personality attributes were confirmed: Intuition, Androgyny [Tender mindedness (M); Tough mindedness (F)]; Perceiving; Introversion; Thinking; Emotional Intelligence (self-esteem); Openness to Experience; Conscientiousness; Resilience; Perfectionism (Self); OE’s ( Intellectual, Emotional, Imaginational). I collected data until I had numbers of at least 200 per instrument. Several studies ensued.

Work on Creativity and the Creative Process

Besides thinking up the Pyramid, I seem to have become known for my work on creativity. The impetus was this: I was troubled by the emphasis in our field on divergent production, and on the positivistic creative problem-solving hegemony, as no creators whom I knew nor whom I had read about used either in their creative processes. I have a high tolerance for ambiguity, but these exercises taught in most programs for teacher training in gifted education seemed to be simplistic and, while fun, to have no relationship to what really happened while creating. I decided to go my own way, to do a little risk-taking, and began to teach an interdisciplinary studies class to undergraduates, revising the course subsequently for the graduate students, using a set of exercises I designed that imitated what real creators really do while creating. My teaching motto is “What is the Image?” and these exercises use a lot of imagery.

The books, Understanding Those Who Create (1992, 1998), and Understanding Creativity (2004) were received quite well, and I was invited to give keynotes, workshops, presentations, and to contribute chapters to edited books. I derived, from the biographies, interviews, and memoirs, three categories of themes:

(1) The Five Core Attitudes for Creativity (Risk-Taking; Group Trust; Openness to Experience—originally called Naivete after Jung–; Self-Discipline; and in 2004 I added Tolerance for Ambiguity.)

(2) The Seven I’s (Improvisation, Insight, Imagination, Intuition, Imagery, and Inspiration). I am contemplating adding another “I”—Intentionality—to go along with the “Thorn.”

(3) General Practices for Creativity (Exercise, Ritual, A Creative Attitude, Study of the Domain, Meditation, Divergent Production practice).

I have files of examples and direct quotations from real creators in various domains of how they use these in their own creative practice and process, so when I am asked to write a chapter or to give a speech, I can use different examples from different domains. I continue to read authorized and unauthorized biographies, memoirs, and interviews, and continue to collect, classify, and categorize these, gaining insight into the lives and practices of creators.

Another impetus: A professor teaching teachers is required by the teachers’ needs, to be practical, and so I also made a book of these exercises emphasizing what real creators do while creating—Creativity for 21st Century Skills(Sense, 2011). I have field-tested these exercises for 26 years.

Evolution

The Piirto Pyramid experienced a shift in 1997. I had genes as an environmental sun, and I moved it to the structure of the Pyramid, beneath the ground. The concrete memory for this was a tour of one of the pyramids in Giza, where we scrambled on stone paths in dark corridors beneath the surface.

The creativity work evolved from Four Core Attitudes to Five, and the Six I’s evolved to Seven I’s—and probably, soon, an eighth.

Hindsight

Forty-two years ago, in 1977, when I prepared for an interview to be a coordinator of programs for the gifted in a rural county nearby, I had no idea what would ensue. I entered the field blind and I was not sure I even believed in a differentiated education for bright students, though I was always in the “A” class in junior high and high school, during the early days of tracking. I became an advocate for very practical reasons. It was my job. My job put food on the table for my children and me, and bought furniture, gas, and books. Even when I entered higher education as a professor teaching teachers for an endorsement, I was writing these books because I wanted tenure, and at my small university, textbooks count for tenure and for a full professorship. Receiving a trustees’ distinguished professorship was totally surprising, since two of the previous three recipients attended there as undergraduates. I was an outsider and they were good to me.

When I worked directly with bright students, getting to know them, I saw the dire need for special programs. Special programs might not be necessary in schools that already have advanced course options, and highly intelligent, skilled teachers who know their subject matter, but they are drastically necessary in smaller rural schools, and in urban areas—where poverty limits the choices and educations of all students—but especially for bright students. My five years working with the students at Hunter College Elementary School, and nineteen years working with rising sophomores and juniors at a grant-funded summer honors institute convinced me that we were helping, and that our work in writing and researching about these students had merit.

I write easily and have a pretty good memory. These helped me in doing research. My background as an English major and literature teacher helped me with critical thinking. Not having studied with a mentor helped me to be a maverick, as I didn’t have to please or further the work of anybody. I was free to carve my own path. Besides talent development, creativity, and creative writers, I have also published work about curriculum theory (thought pieces, arts-based inquiry); the Dabrowski theory (autoethnography, mixed methods, MANOVA); subcontinent Indian education (portrait, textual analysis, poetic inquiry); and depth psychology (thought pieces). And I have been rewarded with lifetime achievement, creativity, and distinguished scholar awards—even an honorary doctorate. As my mother would say, “The world is so full of a number of things, I’m sure we should all be as happy as kings,” quoting Robert Louis Stevenson. It’s been a good run.

References

Bloom, B. S. (Ed.). (l985). Developing talent in young people. New York, NY: Ballantine.

Carroll, J. B. (1993). Human cognitive abilities: A survey of factor-analytic studies. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Romer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100, 363-406.

Gottfredson, L. S. (2001). Intelligence and the American ambivalence toward talent. In N. Colangelo & S. G. Assouline (Eds.), Talent development IV: Proceedings from the 1998 Henry B. and Jocelyn Wallace National Research Symposium on Talent Development (pp. 41-58). Scottsdale, AZ: Great Potential Press.

Gagné, F. (1985). Giftedness and talent: Reexamining a reexamination of the definition. Gifted Child Quarterly, 29, 103-112.

Hillman, J. (1996). The soul’s code: In search of character and calling. New York, NY: Random House.

Jung, C. G. (1965). Memories, dreams, reflections. New York, NY: Vintage.

Kaufman, J. C. (2012). Counting the muses: Development of the Kaufman Domains of Creativity Scale (K-DOCS) Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. DOI: 10.1037/a0029751

Kerr, B.A., & McKay, R. (2014). Smart girls in the 21st Century: Understanding talented girls and women. Scottsale, AZ: Great Potential Press.

Meeker, M. (1969). The structure of intellect. Columbus, OH: Charles Merrill.

Noble, K.D., Subotnik, R.F, & Arnold, K.D. (1996). A new model for adult female talent development: A synthesis of perspectives from Remarkable Women. In K. D. Arnold, K.D. Noble and R.F. Subotnik (Eds.), Remarkable women: Perspectives on female talent development (pp. 427-440). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

National excellence: A case for developing America’s talent. (1993). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. Office of Educational Research and Improvement.

Piirto, J. (2016). The Five Core Attitudes and Seven I’s for enhancing creativity in the classroom. In J. Kaufman and R. Beghetto (Eds.). Nurturing creativity in the classroom, 2nd Ed. (pp. 142-171). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Piirto, J. (2011). The Piirto Pyramid. E-book on Kindle and Nook. Reynoldsburg, OH: Sisu Press. Also, at my personal website: at https://janepiirto.com/?page_id=626

Simonton, D. K. (1984). Genius, creativity, and leadership: Historiometric inquiries. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press.

Sklar, K. K. (1973). Catharine Beecher: A study in American domesticity. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Subotnik, R. F., Kassan, L., Summers, E., & Wasser, A. (1993). Genius revisited: High IQ children grown up.Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Tannenbaum, A. J. (1983). Gifted children: Psychological and educational perspectives. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Vuyk, M. A., Kerr, B. A., & Krieshok, T. S. (2016). From overexcitabilities to openness: Informing gifted education with psychological science. Gifted and Talented International, 31 (1), 59-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15332276.2016.1220796

Jane Piirto bio:

Jane Piirto is Trustees’ Distinguished Professor Emerita at Ashland University. Selected awards include the Mensa Education and Research Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award (2007); the NAGC Distinguished Scholar (2010); the E. Paul Torrance Award for Creativity (2014); the WCGT International Creativity Award (2017); and an Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters (2004). Jane has 100+ scholarly publications in peer-reviewed journals and edited books. As a creativity researcher, in the spirit of having expertise in a recognized creative artistic domain, she has also published 225 + separate poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction works in literary venues. Jane has 12 single-authored books: Creativity for 21st Century Skills; Understanding Creativity; “My Teeming Brain”: Understanding Creative Writers; Understanding Those Who Create (2 editions); Talented Children and Adults (3 editions); The Three-Week Trance Diet; A Location in the Upper Peninsula; Saunas. She has edited one book, Organic Creativity, and co-authored one book: Luovuus. Since 1974, Jane has presented 300+ keynotes, scholarly studies, workshops, readings, and consultations on 6 continents. Jane has a B.A. in English (Northern Michigan University, 1963); an MA in English (Kent State University, 1966); an M.Ed., Counseling (South Dakota State University, 1973); and a Ph.D. in Leadership (Bowling Green State University, 1977).