Fish Scream (short story)

FISH SCREAM

FISH SCREAM

A Short Story

© Jane Piirto. All Rights Reserved.

Kathy backed the van down the ramp slowly, so that the trailer submerged and the boat began to float. Sarah unwound the tangled rope and tied the unwieldy boat to the weathered pole on the wooden dock. Kathy, walking the trailer arm like a highwire, unhooked the boat from the trailer winch. They were quiet and methodical, the process engaging them.

Kathy walked back up the trailer arm then, her old high school tennis shoes already wet, and she jumped off onto the ramp, climbed up the step into the van, and fast, wheeled it up into the parking lot, the empty trailer swift behind her, parking it alongside the other boatless vans and pickups and automobiles slanted next to each other with their empty long metal trailers.

Meanwhile Sarah had climbed up and jumped down into the boat and was trying the running lights and stowing the gear. She unsnapped the last corners of the canvas cover and folded the heavy thing into a clumsy amorphous heap onto the small deck at the bow.

“You girls need any help?” A man in the next boat slip, with his friend.

“No thanks, we can do it ourselves,” Kathy answered, as she carefully balanced, then jumped into the boat from the dock, a canvas bag of thermoses and sandwiches slung over her shoulders.

“This is a maiden voyage,” Sarah said to the man, smiling. Sarah had a nice streak in her, even while Kathy acted annoyed.

“You two sure are some maidens,” the man said, responding to the pun with his eyes on Sarah bent over in tight jeans, storing gear in the console.

Kathy noticed him looking at Sarah. As usual. Nothing had changed. Sarah was still Svelte Sarah, and Kathy was still Fat Kat.

“Thanks,” Kathy said to the man, smiling with her lips.

“So what you doin’ down here so early?”

“Going fishing,” Sarah said. “Going fishing for walleyes; we heard they’re catching them off the Sister Island reefs.”

“Fishing, hey? Been a long time since I seen women fishing without their husbands. Alone, without nobody, I mean.”

“Our husbands were lost at sea,” Kathy said, as if she were joking. “We figure they’re in a life raft somewhere, and we’re going out to find them.”

“No, really,” Sarah said. Not only Svelte but Polite. “She’s just kidding.We’re not married. But we like to fish.”

The man looked from one to the other, and focused on Kathy. Finally he said, “You’re a funny one, ain’t you? Hey, you’re real cute. I like a girl with a sense of humor.”

Even if she is fat? Kathy wanted to say, but remembered she wasn’t fat anymore.

“Let’s go now,” Sarah said to Kathy, who seemed about to say something else. “See you!” Sarah waved to the man and turned the key. The outboard churned right up. “Nice motor,” she said to Kathy. “Nice man.”

Kathy shrugged. She climbed back onto the dock, unhooked the rope, and threw it onto the boat as it started to back up. Then she hopped in herself, over the bow rail, as Sarah eased the boat out of the dock area. Sarah smiled then, and waved to the men. “See you!” Then to Kathy, “Can’t you even be friendly anymore?” So Kathy waved too.

Once in the channel, Sarah snapped it to forward, and they moved slowly up the river to Lake Erie, following the buoys, keeping the wake to six inches.

“This boat sure has guts,” Sarah said. “Just like that guy at the rental place said. Listen to it.” The motor and the propeller sounded solid and strong, and the bubbles of muddy river water were reassuringly rapid as they burst in foam on the surface.

“Well, so far so good,” Kathy said. “Do you think we’ll be able to do it?”

“Sure, why not?” Sarah said. “Look how well we’ve done already. No trouble at all launching, and that’s the hardest part. We did it like pros, didn’t we?”

“Just like she said at my last session,” Kathy said. “‘Face fear so you’ll lose it.’ I feel fine.”

“So do I, Kath. Helping you with this will help me, too. We’re gonna do it.”

The lake is black and quiet. The sky is black and starless. Their boat is the only lighted object, bobbing a little as it drifts with the soft south wind. Kathy and Philip are in the galley, half-drunk from wine, and joints, and each other. Still turn each other on, after all these years. They touch and dance and rev each other in the narrow aisle between the bunks and the galley. The music is old Johnny Mathis, dreamy “Chances Are,” from a station across the lake in Canada.

Sarah and Ross are forward, asleep already on one of the bunks in the vee of the bow. Sarah sleeps with her back into Ross’s front, spoon-style. His arm encircles her and they are secure, there. The gentle bobbing of the boat, the dull slap of small waves, a lullaby, a rocking chair.

“Kathy, stop it. Just stop it. Nothing happened. You avoided trouble. I’m not steering. Now, do it!” Sarah was as stern as if Kathy were her reluctant child, though she couldn’t quite hide her shaking from the obvious close call.

They rounded the last buoy and Kathy let the throttle out, this time in safety. The boat lifted in the water in a surge of power; the bow tipped out; they sped all out full onto the lake. The sun was beginning to shine. It was just after dawn and Lake Erie was a flat plastic bag, reflecting the golden light. There was nothing ahead but the horizon, and the two women aimed to hit it, Kathy standing at the helm, Sarah sitting in the swivel seat next to her, her hand steadying herself by grasping the chrome rail next to the control panel. They threw their heads back and took the wind full force to the face, and as they laughed out loud, their laughs were lost as if they hadn’t.

It was a quick two miles northwest to the fishing grounds. The paper said walleyes were being taken just off these reefs, in 30 feet of water. Kathy gave Sarah the controls as they slowed down, circling the bobbing boats already out there. Kathy pulled the tackle box from beneath her chair. She signaled, and Sarah cut the motor.

The barge churns slowly along, its cables beneath the surface, but they wouldn’t be seen anyway, if they were above; the lake is black and the sky is black. The barge captain falls asleep for a few minutes, it is so quiet and peaceful. Tomorrow is Sunday and he will be away from home for the second weekend in a month, and it was his turn to usher at church; he had to call the minister and apologize. At his age, with his seniority, a man shouldn’t have to work weekends.

“Mickey sure picked us a lot of nightcrawlers,” Sarah said, her hand plucking in the dirt of the bait can for a good, fat one. Once her fingers found the right one, she pinched it in half. “He said, ‘Don’t say ick, Mom, when you put them on the hook, the way you used to when we’d go fishing with Dad.'”

The women baited their hooks. They were using this year’s dynamite fish killer, the Erie Dearie–“guaranteed to get fish”–the man said at the small carry-out store where they had bought their licenses.. Last year it had been the Purple Passion. Fishermen seem to believe that fish change preferences for lures, from year to year, as if fish had thoughts, and decide they will or will not go for certain colors and flashes. Kathy used to tease Phil when he’d buy just one more lure, guaranteed to catch a million walleye.

She tried the action of the lure in the water alongside the boat, and it dodged and dove and swam. “A real alluring lure. Perfect.” A thousand times she’d seen Phil do this same test–well, more like ten or twenty times–her memory has begun to magnify everything they used to do. She felt tears smart, then stopped herself. “Process. The process will take away the feelings,” she mumbled to herself.

Sarah started the motor up again and positioned the boat to troll the fishing grounds very slowly. “No, let’s just drift,” Kathy said. “The wind is strong enough.”

Sarah fished from the swivel seat next to the control console, and Kathy sat on the seat in the stern. Kathy cast the line 30 feet behind the boat, which was drifting northeast, pushed by the southwest wind. She let the line trail behind the boat, content to settle into reverie, to sit still. Sarah, though, cast and reeled and cast and reeled. “I need to move it,” she said. “Drifting a line is boring, almost as boring as still fishing. Ross always hated sitting and letting a line in the water; I guess I do, too.”

“Remember how they used to razz each other about that?” Kathy said.

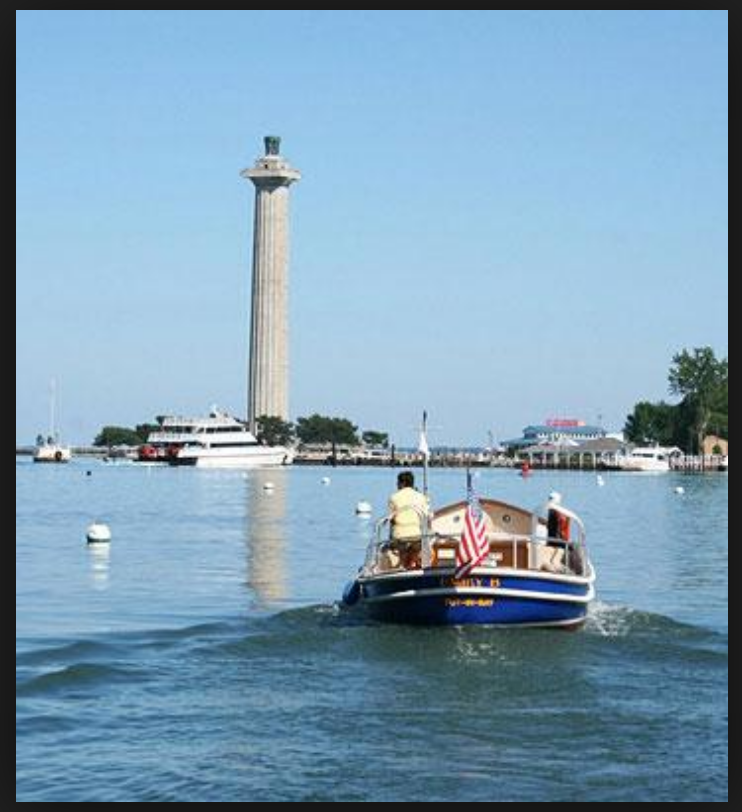

“Well. Yes,” Sarah said. “Remember how we’d dock at Put-In-Bay, and then party on shore, without kids for a change?”

“Remember that time Phil got a little too much beer and turned a cartwheel right next to the cannon? Sprained his wrist so I had to bait his hooks the next day?” Kathy laughed. She stopped, and then laughed again, a pleasurable laugh of reminiscence, not a wrenching, sob-torn laugh. It had been a long time since she’d laughed like that.

“Remember the time we went skinny-dipping at night, just the four of us? Heading over to Pelee Island for the weekend?”

“The water was so warm you could scarcely feel it; it was as if the water were air,” Sarah said.

“We got a lot of fish that weekend,” Kathy said.

Just then Sarah hooked one, set it, and reeled it in. “Goddamn sheepshead,” she said, as she swung the fish to her chest and caught it, squirming, grasped it firmly behind the gills, pressing the rod between her legs as she wiggled the hook loose and threw the fish back in. “God, I can’t stand that. The fish screams. I can hear it. It just stares me right in the eye and screams.”

“Some people eat sheepshead, you know,” Kathy said.

“Well, if I were a fish, I’d be a sheepshead, because I’d have a much better chance of surviving, with everyone throwing me back, even if I did have scarred jaws and a raw mouth. Poor game fish. Being in demand like a walleye, perch, or trout, you can get killed.” She stuck another piece of nightcrawler on her hook and cast a perfect cast, letting the release go at just the right time.

“Hey! Lights!” Phil goes halfway up the steps and sees the barge about 150 feet away, to the north. They are on its shore side. “It’s one of those big barges that are dredging the Huron River channel,” he says. “It goes so slow it’ll take all night to get there. They must dump far out.” He starts up the motor, just to be sure, as Kathy slides the cover on the inboard. The motor idles, ready for an emergency. “Hey, what’s up?” Ross emerges from the bow compartment. “Nothing, only a barge passing,” Phil tells him. “Shit, can’t even be alone in the middle of the lake,” Ross says. “Go back to sleep. We’ve got it in sight. Everything’s OK,” Phil says. They are drifting parallel to the barge, and then it passes them. It is July, and balmy.

The wind was switching from south to north, and the boat was starting to toss on the waves and down in the troughs. Then Kathy hooked one. She reeled it in. “Phooey. Another sheepshead.”

Then Sarah. This time, it was a good walleye, a 20-incher. She measured it with her thumb-to-little-finger span. Ross’s span was nine inches; he’d had big hands. Hers were small, 7 l/2 inches twice, plus three fingers. “Whooee! Fish fry tonight. Let’s get more! They’re starting to hit, barometer going!”

Soon the sky was gray and they were bobbing up and down on the rolls. Boats were starting to head for shore. “Let’s troll just a little longer,” Kathy said, a spinner in her fingers and the line in her teeth.

“Goddamned Lake Erie,” Sarah said. “Storms sure don’t give warning.”

“I thought it wasn’t supposed to get bad until this afternoon.”

“So did everyone else,” Sarah said. “But let’s try for awhile longer. I’ll turn the CB on, so we’ll have contact with shore and the other boats.”

They tried casting a few more times, but the seas were getting so rough they couldn’t feel their lines. ]The waves were splashing into the boat by now, and soon they were drenched and shivering, even though the temperature couldn’t be under 60.

“Well, what do you think?” Kathy said. “Have we done it? Proved we can face the lake again?”

“Sure we have. I feel real scared, though, still. This is going to be a storm. Let’s get out of here.” They racked the rods. Sarah revved the motor and they started towards shore. On the CB, they heard a faint distress call. “Send the Coast Guard. Send the Coast Guard. Boat won’t start up. Motor swamped. About a mile off Mallard Creek.” Kathy started to shiver, as the calls– “Emergency! Emergency! Send the Coast Guard”–came over the crackling radio.

Sarah was coaxing the boat slowly over the roiling. Off in the distance they saw the flashing lights of the Coast Guard boat cutting across towards shore. “Thank God,” Kathy said.

Their boat was being socked on the bow as they hit each wave. They braced themselves with their knees and hips against the console. The situation was tenuous. Again and again they rose on a wave and fell into a trough, rise and fall, rise and fall, as the water splashed, mercilessly irregular. When the boat dropped, it seemed as if the cushion of water gave way and they were going to go straight under.

“We’re going to drown, we’re going to, we’re going, we’re going to drown!” Kathy put a life jacket on and handed one to Sarah, tossing and twisting as she struggled to keep her footing. She was hit by a panic so deep she wanted to scream her head off, to throw herself overboard and be done with it, to dance like a banshee. “We’re ditching. We’re going to ditch!” She pulled Sarah’s arm from the wheel and the wheel spun rapidly as the boat careened and began to take a header into another wave.

“Stop it! Stop it! Sarah pushed Kathy off with one shoulder, like a football player, and grabbed the wheel back, with her other arm. Kathy fell over the swivel seat and onto the deck.

A barge has passed them at a safe distance. All is quiet again. Phil puts his arm around her and is moving to kiss her, “Kathy, my woman, my wife,” there in the quiet summer night on the deck, with the lights moving off.

Suddenly there is a loud grating sound and suddenly they are in the water. Kathy is tossed head first, amid flying life cushions and towels and tennis shoes, into the water. It is black. She hears herself screaming, and takes a lungful of water, that burning sear, and she hears Phil’s shouts, and Ross’s. She has banged her head on something, and it is throbbing. The boat is cut in two.

The fall to the deck knocked Kathy sensible. She struggled up and faced Sarah, bracing against the rail. “Sarah I’m sorry, I panicked again, I did it again, didn’t I, I’m sorry, Sarah. Sarah?” Sarah gave her a disgusted look that said I went through it too, and I’m not acting like a maniac.

Then Sarah softened her gaze and motioned, “Here, it’s all right. You take the boat in. Come on, you can do it!”

Kathy took the wheel and they slowly chugged, up and down the waves, inching steadily toward safety. Yet the panic stayed, her heart clutched in on itself, her breath almost stopped. She could barely see, barely breathe.

She is swimming. The lights of the hospital are bright, as they wheel her into the emergency room. It is like the other time, the other emergency room. Only now she is crazy, she’s got a bottle of pills in her stomach, she is crazy with screaming. Drifting, drowning, for two days, towing a dead man from a rope around her waist.

The seas were high, but she fought them with all the strength in her forearms, holding the wheel steady, pointing the bow to the river mouth just over the horizon. Sarah had her back to Kathy, looking towards shore, too. Then, “Look!” Sarah pointed. Just below the horizon they saw the neon pink of the international distress flag, a small patch in the gray of the water and the lighter gray of the sky. It was being waved, so far as they could see with the waves so high, by a figure standing up in a small boat that intermittently appeared and disappeared according to how their bobbings were synchronized.

“Someone’s in the water! There’s three heads!” Sarah pointed again.

Kathy automatically swung the boat towards them. Her panic no longer selfish, subsided. There was a small outboard with four large men–overloaded–circling three bobbing balls in the water. One of the men was standing up in the small boat, waving the distress flag spread between his upraised arms. Kathy remembered the old warning. She had said it to her kids over and over, and to the kids she used to counsel at summer camp. Never stand up in a canoe. She shouted, “Never stand up in a canoe!” Her words went the way of the wind and of the water.

The smaller boat was lurching on the waves, having more trouble than their deep-hulled 19-footer. The man with the tiller was having trouble trying to keep it steady. The three people in the water were clinging to the bow of a turquoise boat that had sunk, stern down, into the water. As they neared, they made out two men and a woman. The two men had the woman sort of propped upon their shoulders, clinging higher on the bow of the sinking boat, while they tried to boost her up there and still keep from swallowing water themselves. Kathy passed too close and the boat’s wake sloshed water in their faces.

She widened her circling. Then she approached them, very slowly so she wouldn’t splash, cutting the motor as they got near. Sarah had moved to the bow of the boat and she threw a lifeline to one of the men. He didn’t catch it, and almost lost his grip on the sunken boat, in the try. Kathy backed out a little and came in again. Sarah threw again. Kathy cut the motor; dead sound. Only the weather. The man caught the line. He was wearing a brown leather jacket, like a bomber pilot, and he had a gray face.

Kathy left the wheel and stumbled a little, to the bow alongside Sarah. The men in the water said, “Get Ruby! She can’t swim!”

Ruby looked up at the height of the bow at the women leaning over toward her. “I can’t make it, it’s too high.”

They are all so calm.

“Sure you can,” Kathy said. “Give me your hand.” She reached down off the bow and grabbed Ruby around the wrist in the lifesaving grip. But Ruby was no lightweight. She was hefty, in her fifties or sixties, flabby, not agile. Together the men in the water tried to push her up further, on their shoulders, towards Kathy, as Kathy pulled on her arm. Then Sarah leaned over the very front side of the bow, yelling, “Lift your leg, Ruby! Lift your leg!” Kathy pulled on the arm and Sarah pulled on the leg and somehow they lifted Ruby sideways up enough, so they could reach the elastic waistband of her plaid stretch pants.

“I can’t! I can’t do it!” Ruby was crying.

Over and over the days in the water replay themselves. Years in the water, clinging to a life preserver, a life preserver around Phil’s head. Phil is dead. The sun rises and no one comes. The hospital lights are bright this time, as bright as when the Coast Guard brought her in, only these men aren’t the Coast Guard. Screaming in her sleep. Six months and still screaming, and then it is too much, towing a dead man by a rope around your waist. Cut the rope.

“I can’t!”

“Ruby, you can.” Kathy noticed that her voice was strong and calm. “Now come on. Lift your leg against the boat.”

Sarah. Speaking in her calm voice, “I’ve got you, Ruby. She’s got you. C’mon, Ruby. Try!”

Finally the two women, finding strength in their arms and legs that they didn’t know they had, rolled Ruby–slung her really–over the rail onto the raised deck, and there she lay, panting and spitting, in a heap, collapsed onto the tangled boat cover. Sarah fussed over her, murmuring, “It’s all right. You’re safe. It’s all right. We’ve got you.” Ruby nodded, dumb and spent.

Now for the men. The boat was bucking. The waves seemed larger. The two men clung to the bow of their sinking 16-footer. The small motorboat was still circling the scene, four large men helpless in a small craft. Kathy was conscious of their will and energy as they watched her and Sarah perform the rescue.

“Come to the stern,” Kathy said to the man in the brown jacket, who was still clutching the lifeline. It was twisted into his hand, around it tight. His arm must have been pulled out of its socket by now. “It’ll be easier to get you up from down at the stern,” Sarah said. Kathy returned to the wheel to steady the boat.

Sarah reached for his hand as the boat bobbed. She braced her knees against the inside rail of the boat and said, “Come down here with me, along the rail. I’ve got you. You’re safe.” She gripped his hand in the firm grip they’d used on Ruby.

He looked up at Sarah as if he didn’t believe he could make it. He told her, “I’m all right, now you’ve got Ruby.”

“Come on, Sarah said, and Kathy could see her fix her eyes on the man’s eyes, though she couldn’t see the man. It was the same pity as for the screaming fish.

“Come on, you can do it. I’ll guide you down to the stern and we’ll both help you up. She pulled him up so that he could get his other hand around the rail, and Kathy could see his blue- white fingers curl around, and grip it.

Sarah and Ross are thrown free. In the black water Ross yells, once, “Sarah! I’m OK! Look for a cushion!” and then they are separated. A black, large form slowly passes between them. Another barge, unlighted. They find Ross’s legs hung on the steel cable the next morning, when the barge reaches the mouth of the Huron River. Sarah pushes a boat cushion in the direction of what she believes is shore, and a Lyman inboard-outboard picks her out of the water at dawn.

“I don’t have a life jacket,” the man whispered as he dangled off the motor end of the boat, his eyes still on Sarah’s as if he is confiding his deepest secret. Kathy read his lips. “And I’ve taken a lot of water. Bless you. Bless you.”

Kathy moved to the stern to help them, and saw, as if in a tableau, Sarah’s eyes locked on the man’s eyes, Sarah willing him to be rescued, her lips moving as if saying a prayer, in quiet words of encouragement. They were as intense as lovers. As they passed the life-jacket compartment, Sarah reached backward, still keeping him with her eyes, and pulled a jacket out. She reached down to put it around his neck, but she couldn’t reach low enough to hook it. She tied it, one-handed, and almost went over the rail as a wave hit them broadside. But she regained her footing, bending her knees and pressing them against the inside of the rail, and she led him, inched him, down the side of the boat and around to the motor, where Kathy waited. Kathy knew then that Sarah needed for the man to be rescued as much for herself as for the man.

The barge captain didn’t know he had hit a boat. He was surprised, the next morning, when they discovered a pair of legs and no torso, straddling the cable, caught by a bloody rag that looked as if it had been a shirt. By then they were thirty miles down the coast. The small barge the large barge had been towing on a submerged cable, had been unlighted. There was also a frayed rope wound around the cable, and a wet blanket dragging.

The man in the brown jacket seemed reassured at having a life jacket, as if he believed in rescue. “Bless you, bless you,” he kept on saying. Kathy pulled on one arm and Sarah on the other. He placed his foot on the blade of the big motor and somehow they hoisted him over the back end and flopped him between them onto the seat, over the bilge well.

“Are you all right?” Kathy asked. The man was lying over the sea, and Sarah helped him up to a sitting position. “Yes. I’m fine. Fine. Where’s Ruby?”

“She’s fine, too. Up in front,” Sarah said. Ruby did not look fine, though. She was lying quite still, and still panting. Kathy and Sarah looked at each other. Stroke? Heart attack? None of these people looked in particularly good physical shape, Ruby especially. Sarah quickly made her way along the rail and sat Ruby up, swaddling her with the canvas boat cover. “This’ll have to do until we get to shore. We don’t have a blanket. Are you all right? Ruby nodded, but her face was blue and purple and white.

“Get my buddy. Get my buddy,” the man said to Kathy.

“We are,” Kathy said. By now they had drifted quite a way from the man in the orange life jacket clinging to the bobbing bow of the submerged turquoise boat. The bow was only two and a half feet above the water. It seemed to be sinking faster.

Kathy circled him again, and approached from the downwind side, cutting the motor as before. Sarah threw him the rope, but he didn’t even try for it; he was clinging to the bow with both arms, with all his might. His face was white with fear.

Kathy had to circle again, and they drifted right next to him, approaching with the wind. Sarah threw him the rope again. “Cut the motor!” She reached over the bow to throw the line, and this time he relinquished his clinging to the sinking boat and caught the rope. Sarah pulled him in, though he was reluctant to leave the bow of his boat. “Now I’m going to lead you down the length of the boat to the back. It’s easier to get in back there.”

“You’re all right, you’re going to be all right,” Sarah said as she led the man back. Together Kathy and Sarah and the man in the brown jacket tried to heft the man in the water into the boat, but the motor was turned too much for him to have enough space.

“Turn the wheel! Turn the motor!” Sarah moved quickly back to the console, and turned the wheel, but it was already taut. “Turn the goddamn wheel!” Kathy wondered at Sarah’s slowness.

“I am, goddamn it, I am!”

“The wrong damn way!” Kathy leaped back to turn it the other way. The motor straightened out and they pulled the man in. She sat him next to his friend, and as they set out to get them to shore and to help, he waved back at his sinking boat and said, “Goodbye, Starcraft.”

The four men in their small outboard rode alongside them for awhile, and then Kathy gunned the motor and passed them. Sarah waved back to their salute. The waves were smaller now, and the rain was cold and steady, so the trip back was an easy one.

Later, over beers in the marina, Sarah told Kathy, “You know the guy in the jacket? He told me he’d been rescued once before, in the North Sea, during World War II, in December 1943, when his boat was hit by a sub.”

END

Publication history:

Piirto, J. (2002). Fish Scream. International Journal of Qualitative Inquiry, (2002).

Piirto, J. (1983). Fish Scream. Sing, Heavenly Muse! (59-68). Winner: Established Writers Category in Fiction