A Creative Nonfiction Essay

© Jane Piirto. All Rights Reserved.

It had stopped drizzling. We wheeled the rented VW Golf into the small town, our first view the view of the river, and then, behind the trees, of the church. My mother pulled out the Christmas card she had carried here, from half the world away. It was a black and white photo of this very church, in a yellow cardboard holder, photographed from across the river at a site we couldn’t pick out now.

She had taken the card from her mother’s effects when cleaning up after her mother died. Parking the car in a side road in one of the few available spots, my mother asked a man rushing with the rest of the people, why all the traffic, and where was everyone going? “National baseball tournaments,” he said.

Baseball? In Finland? Here, in Ostrobothnia, in Vimpeli, a small small town on the shores of a lake called Lappajärvi? Had we come around the world to a baseball tournament? Our curiosity piqued, we resisted the temptation to follow the crowds, and went toward the church instead.

The date on its stone gateposts said it was 150 years old, and the metal gates were held by a large iron clasp that we lifted. The gates slowly swung open and we entered the church yard. The bell tower rose above us, the yellow clapboard siding newly painted, the cross on top of it pointing straight.

We began to look at gravestones, looking for the name of her maternal grandmother and my great-grandmother, Änna Kärnä. All four of my grandparents came from Finland, which means that all eight, sixteen, thirty-two, of my great-grandparents did, as they had for my mother. My children are only half-Finnish.

When I got married, my aunt told me, “But he’s not Finnish. Your children will be half-breeds.” The quiet of the walled-in churchyard seemed paradoxically medieval, as we heard the echoed bellow of the announcer from the field.

My mother said, “She said she lived across from the church,” as our search ended. No people with those names who had the right dates. This, our first cemetery, did not yield the information we wanted. But what information did we want? To find the burial place of our ancestors? To find living relatives? To get a sense of where our people had come from? To touch our pre-conscious past? All of these and perhaps more.

As we crossed the street, my mother read the name on that Christmas card that had been sent to my grandmother so many years ago, from a friend in this village, Vimpeli, where my mother’s mother, Ida Kärnä, had grown up. I saw two women emerge from the house across the street, and said to my mother, “Perhaps they know. That house is across from the church.”

My mother opened the painted white gate, walked the path next to the clotheslines, and greeted the women. “Do you know any Peltolas?” she asked. The lead woman looked at the card, looked at the name, and said, “Yes, sure. She lives just over there. Let me take you.”

We followed her, and my mother chatted in Finnish with her, telling her we had come to try to find some information about her mother’s mother. A block away, we entered a small garden apartment in what looked to be old folks housing; at least there were the old men sitting outside on the bench, and a small and institutional feeling to the apartment. My mother knocked, and an old woman, disheveled and disoriented from the nap we had interrupted, answered.

We entered, and our guide asked Mrs. Peltola whether she had sent the card. She looked at it, puzzled, and then admitted it was her handwriting, but she couldn’t remember sending it, nor could she remember to whom she had sent it.

My mother and her sister and two brothers were the children of two Finnish immigrants who had come to the United States and had settled, met, and married in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, in the second decade of the twentieth century. My aunt was born in 1915, my mother in 1916, and my uncles in 1917 and 1919. Their mother, Ida Kärnä, my grandmother, had never talked about her parents, except for a few references to her mother.

Strangely, my mother and her siblings had not bothered to ask, sensing my grandmother’s reluctance to discuss her past and the reasons she had immigrated. Finally, when my grandmother was in her eighties, my mother had asked her the hard questions that had been troubling her, and my grandmother said that she had been illegitimate, but that she occasionally saw her father, Antti Santala, when she was growing up, remembering that he had played horseyback with her on his knee.

My grandmother gave no more information, except that my mother always knew in the way that children know things, that my grandmother loved her mother dearly. By now, what had happened here in Finland in the nineteenth century, perhaps a furtive night between a young couple of different social classes, the maid and the master, has produced four children, eleven great-grandchildren and fourteen great-great grandchildren, with the latter now reaching childbearing age.

And now my mother, over 70, had come to Finland for the first time in her life, with me. We were attending a conference to be held in Helsinki and at the University of Kuopio, called “Reunion of Sisters,” where 300 Finnish women and Finnish-American women were to meet and talk. I was on the Literature Task Force, since I write fiction and poems, and I was to present a paper on Finnish-American Women Writers.

One of my writer friends said, “You and who else?” “Well,” I said to him, “Jean Untinen Auel is one of us. You know her Clan of the Cave Bears and The Mammoth Hunters? Also, the poet Judith Makinen Minty. ” I was also to perform one of my poems with an actress reading the Finnish translation, at one of the evening events.

What a great chance for my mother, a widow who lives in Ishpeming, Michigan, and who had never been to Europe, to come along. What a great chance for us to travel together. My mother has spoken Finnish all her life, and has been studying how to read and write the language for the last few years in a night class taught by a Finnish immigrant. Finnish has thirteen cases and many endings, and words get added to each other, so that one can have a word with as many as fifty letters.

My knowledge of Finnish is odd words, for food mostly, and I know that Finnish words are all pronounced with the accent on the first syllable—HELsinki, and SAUna. That’s “sow” as in female pig, or as in “ouch,” and not “sow” as in apposition to “reap.”

Besides the sauna, the Finnish immigrants’ other contribution to U.S. culture was the co-op apartment, the first ones having been built in Sunset Park in Brooklyn, in “Finntown.” Even though I attended Suomi College, the only Finnish American college in the U.S., I was so stupid at the age of seventeen that I didn’t even avail myself of the opportunity to study the language of my ancestors, a regret I continue to have as I am pulled into the Finnish-American community by people who write me letters about my stories and poems.

As soon as we got off the plane and rented the car, my mother was one-minded. Go to the Christmas card’s town, Vimpeli. We had spent the night in Tampere, a clean textile manufacturing city with cobblestones and flower boxes, and this was the afternoon of our second day, managing the European sign language and the Finnish language road signs with many laughs and wrong turns.

The roads in Finland are very well-kept, as is everything there, and the countryside most closely resembles the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, or the upper regions of Wisconsin and Minnesota. Lots of lakes, forests, fields. It is no mystery why the Finnish immigrants settled along the northern tier of the U.S. and in Canada. Only about 300,000 Finns emigrated to America, and about 55,000 of them returned. The census of l980 showed about 600,000 Americans claiming Finnish ancestry.

In 1990 I was giving a talk that ended, as I often do, with my reading a poem I wrote about my grandmothers, in Little Rock, Arkansas, and I met a woman from Massachusetts who was half Italian and half Finnish. She said seeing my name and hearing me read my poetry infused with my Finnishness made her weep for the invisible half of her, the forgotten half of her that hadn’t been recognized in immigration history, though a Finnish immigrant is supposed to have been the first president of the U.S., before Washington. And now, here we were, in Vimpeli, after eighty years, trying to find traces of an immigrant peasant girl, her mother, and her illegitimate father.

Mrs. Peltola, couldn’t remember, but she had probably known our grandmother while growing up, even though she is younger. “No matter,” our friendly guide, whose name was Kirsten, said. “We’ll make some calls. Come over to my house and have some coffee.”

We followed and entered. Our second Finnish house. Like the first, there was no grime even in the corners of the entrance porch, but just a rag rug, and shoes on the floor. We didn’t know whether to take our shoes off as we entered, or whether the pile of shoes was only for members of the family, so we left them on. Kirsten showed us into the living room, through the large dining room. The dining room table we passed was piled with fabric. Curtains. She is a custom designer of curtains, and the other woman who now greeted us was her employee.

The other woman, whose name was the same as my mother’s, Helmi, was less effervescent, reticent. They cleared the curtains they had been folding into curtain boxes, off the table, and my mother stayed in the dining room, chatting, while I sat down in the living room and looked around. This was the second time in the last half-hour I had felt like a little girl again, with the ladies talking in Finnish, and me unable to understand them, as had happened so many times in my girlhood.

The living room had a TV, a VCR, easy chairs, some original paintings on the walls, mementos of trips, African dolls, a plaster statue of Venus de Milo about two feet high stood improbably near the wide entranceway. A TV guide in Finnish on the floor. Photographs of two young men about seventeen in what looked to be yachting captain sailor caps, but which turned out to be graduation hats. I recalled similar hats in Bergman movies.

Most times when you enter someone’s home you don’t have time to look around, unless you’re a child who must be silent. I had the time because I was like a child, tongue-tied. The poet Aili Jarvenpaa has a poem about how her children can still recall every detail of the pillows in her mother’s living room, how the crocheted patterns went, because her children had been made to sit while the Finn-talk went around them. When Aili read that poem,

I recalled my own very vivid memories of my grandmother’s living room—her gloxinias in the planter, the satin, fringed pillow from Okinawa that Uncle George sent during World War II, the pink sugar mints she had in a covered green Depression glass dish, the doilies over the backs of the chairs, the mottled wine and green vines on the area rug.

And of course the African violets. My grandmother was one of those people whose African violets always bloomed. I was to find out that all the Finnish homes we entered had success with African violets. Kirsten’s were set in just the right light, with several shades of violet and pink peeping out from the green velvet leaves. I have a theory that African violets only bloom for middle-aged and older women, and then, only for some of them.

I have a corollary that when our African violets bloom for us, we begin the middle-aged stage of our spiritual journey, and often go back to the church. My mother had never seen her grandmother’s African violets. My mother had grown up without the comfort of a grandmother. I had known both my Finnish grandmothers, felt their substance in their hugs. Someone of that generation of grandmotherless immigrants said she always cried when they had to sing that song, “Over the river and through the woods, to grandmother’s house we go.”

The call that kahvi was ready came, and I entered the dining room, where Kirsten had effortlessly whipped out a feast—Karelian pies, heated through; scented cardamom pulla coffee bread, cold cuts and cheese layered in a circle on a glass plate; sliced tomatoes and cucumbers; small cookies with almond flavoring; thin-sliced dark rye bread; and the coffee in demitasse cups with a choice of kerma or maito, real thick cream or milk.

Every restaurant we went into offered real cream for coffee. Memories came to me again, of all the coffee tables I had sat around with my aunts and grandmothers. Particularly vivid is when my aunt was divorcing my uncle. All the aunts sat around the dining room table on Saturday nights and Sunday afternoons, in rooms similar to this one, drinking coffee and dissecting the relationship, always agreeing that he was a rotten guy to give up such a good woman as our aunt.

My cousins and sister did the same thing for me when I got divorced, and I left feeling better, also. Sometimes it is difficult to separate these times from those; women sitting around a table, with the nieces right in there with them, talking about men. One of the residues of my Finnishness that I retain is rushing to offer coffee to any visitor, however unanticipated, at my house. During my childhood, many people used to go “visiting” on Sunday afternoons, arriving unexpectedly at friends’ and relatives’ houses, to great welcomes and good kahvi talk.

The invention of the television has probably isolated us. I remember the visiting stopped about the time that Sunday afternoon football started, during the late 1950s in our town.

While I surveyed the living room, Kirsten had made a few quick calls, trying to find the minister of the church, so we could get a look at the records, but everyone was at the baseball game, she said. I said I wouldn’t mind going to see the baseball game; I had never even heard of Finns playing baseball until this very minute. And here was the national tournament. We all agreed it would be fun to go over to the baseball game. Helmi left for home, her day’s work over.

Helmi tied her huivi or scarf, on backwards, where Kirsten tied hers under her chin. A conscious class difference? We shook hands with Helmi and thanked her—kiitos—as we parted on the street, while Kirsten hung a few clothes on the clothesline before we left.

Kirsten’s husband, Karlo, and their two sons were at the game. We got to the field and Kirsten collared the English teacher from the local comprehensive high school to talk with me and explain the game.

Finnish baseball is called pesapallö.

It was the last inning. Nine innings. But there are five outs in Finnish baseball, and no pitcher. Or the pitcher doesn’t pitch; he throws the baseball up in front of the batter, from the side of the batter, and the batter slams it out into the field.

There are many fielders, and if the batter hits a good one–what is “good” escaped me, for many times a ball would be a good bouncer out to center field, and it would not be counted fair, or it would be a long pop fly and be caught and look like an out, but the batter would run—toward third base. Or maybe I was watching a game in reverse. Then the batter ran across the middle of the diamond towards first base, and then to second, third, and finally home, in a very confusing zig-zag.

The English teacher couldn’t tell me much more than what I was seeing with my own amazed eyes, because he wasn’t a baseball buff nor had he played when he was a kid, and had only been to three games that entire year. He said the rules had always confused him, too. His English, spoken in a British accent, was excellent. The game ended, with Vimpeli losing the national championships to a town just north of Helsinki, and most of the crowd left with sad faces.

A sad day in Mudville. The players on both teams looked like baseball players, all right, stocky, muscular, handsome, not long and lanky like basketball players, nor massive like football players. As in most of the world, in Finland, football is soccer, and Football is called “American Football.” The players all looked like my son. In fact, one of the most striking impressions of being in Finland was how everyone looked like me and my church friends.

Used to the diversity of urban U.S., I was struck by the sameness of faces as is every traveller who goes to any mono-ethnic, monochromatic country. During the entire time there, we saw about five blacks, ten Indians, and four Asians. Students, or travellers, surely.

Finland has a very conservative immigration policy, and an even more conservative refugee policy. Thus, one of the most curious sights was that of the ladies in long black full skirts with aprons and vests and lace-edged caps, whom we saw all over, pushing baby carriages and shopping in the markets, speaking fluent Finnish. I thought these were Bohemian immigrants, but after I asked I found that these are gypsies. At the market in Helsinki, there was a gypsy lady selling very beautiful lace and crocheted tablecloths.

We did not see any gypsy women with booths at any of the other markets we visited, though. Someone told me the Finns still discriminate against gypsies, and that there has been a settlement, or reservation, made for them up near Lapland.

After the game, we were invited to stay with Kirsten and Karlo, in one of the bedrooms upstairs. At dusk, about 10:00 in this northern latitude in August, we drove out with them to their cabin by the lake. Again, deja vu: this was like the cottages many from the Upper Peninsula have on northern lakes, except it was more Finnish in decor, of course.

Karlo had built it all himself; as we entered we gasped. It looked like a picture in an Eero Saarinen or Alvar Aalto coffee table book. Light, varnished wooden floors and paneling shown off by red and white rag loomed carpets running along the floor; a free-standing staircase to the loft in the same gleaming wood; a huge fireplace of stone. Immaculate, of course. Outside, the outhouse, and the sauna, just like at home in the Upper Peninsula.

A truck drove up. “This is a Kärnä,” they said. They had called the Kärnäs they knew, and a young man of about thirty had come to meet us. He and my mother talked a little about what we knew about her grandmother’s brothers and sisters, since all Kärnäs are supposed to be related, and they all decided that we would have to wait until morning, when we could get to the church to see the records.

“And then,” the young Kärnä said, “if there’s nothing there, we’ll take you to The Island.” There is a Kärnä Island on Lake Lappajärvi. I pictured us rowing over in the billowing fog in a silent rowboat to “The Island” to find our ancestral place.

Back at their house, Kirsten had heated the sauna for us in case we wanted to take one. They seemed a little surprised at our ease with saunas. The sauna was in the basement, and Kirsten gave us towels, and pointed out the shower, the faucet for filling the buckets from which we would splash löylyä, cool water from dippers, onto the rocks, and left us.

The sauna was not hot enough, as they probably thought we could not stand it hot, but we didn’t say anything. We came upstairs with wet hair plastered to our skulls, just like at home, and we went into the living room, where they showed us videotapes of their son’s wedding, with the traditional community folk dance that lasted two hours, with accordions and drums and throwing of the parents and the couple up into the air, with stuffing into pockets of money.

My mother woke me up with her gentle voice: “It’s 10:30 and I’ve been over to the church and I’ve found things out.” She had been up at six, as usual, jet lag not having hit her as it had me, and had coffee downstairs with our hosts before they headed across the yard to their curtain shop. My mother had been introduced to the Pappi, or minister of the big old yellow wooden church across the street.

He had gone into the records, and had come up with this information: Änna Kärnä had given birth to Ida Kärnä, my grandmother, my mother’s mother, in 1890. Änna was born in 1854, on December 19 in Lappajärvi , the same day as I was born over eighty years later. December 19. My birthday.

I had been born on the same day as my great grandmother, almost a century later. Änna Kärnä had been a piika, or maid, at the time of giving birth.

Ida had left for the U.S. in 1910, at the age of twenty. Änna had been buried in Lappajärvi, in a family plot, in July, 1933.

Taking awhile to absorb this information, I calculated, and with amazement, said, “Mother, she was 36 when she gave birth to Grandma!” Thirty-six in 1890 must have been very old, especially in a farming community in rural Finland. “The mystery deepens,” I said. My mother didn’t appreciate my humor much, but she asked me whether I thought I was Nancy Drew or Jessica.

“Look, Mother, she got knocked up by some guy from town, playing with the maid. It’s very obvious to me.” I was being deliberately crude, to put some reality into this romantic search. My mother repeated the story her mother had told her about her father playing horseyback with her on his foot with her clinging to his knee and she told me to watch my language and have some respect.

“And he visited once in awhile,” I continued. That’s the story. Grandma was shamed and felt out of place, and that’s why she came to America. Being in this small town, you can see how she would want to come.” And then my mother told me that her mother had said her father, Antti Santala, had wanted to put her in his will, because she was his first child, but Grandma had been proud and refused.

Now all this information was coming out slowly, in dribbles. It’s what intimacy does. My mother and I had not spent so long a time together alone ever, as in a marriage before the children come, and the details were unfolding.

“We go to Lappajärvi,” she said. Lappajärvi, when we consulted our map, is just around the large lake, not far, about 30 kilometers. Before we left, we said our good-byes to the sons, who had come to say their own good-byes. Kirsten gave us linen towels with “Vimpeli” woven into them, as gifts when we parted. I gave them a copy of my novel, and my mother gave them some American scented soap from a Prange’s department store branch in the Upper Peninsula.

Before driving out of town, we stopped to enter the church Grandma had attended, which was festooned with flowers, because a funeral was going to take place. We sat quietly, reverently, and we imagined a young girl here at the turn of the century, sitting in one of these pews, listening to sermons and choirs as the daughter of a maid, a maid herself.

Grandma had also worked at a store, my mother then recalled. The old, weathered building across the street was the old store, kauppa, and we circled it with our cameras and our imaginations, peeking into the boarded up windows, imagining Grandma there selling buttons and nails and coffee.

As we drove around the lake, we talked of how Änna Kärnä and Ida Kärnä must have taken this very road before it was paved, and seen these shores, with these reeds’ ancestors, these farms with their cows situated in picturesque postures. Cows never look anything but picturesque.

We were in a companionable dream, seeing these familiar yet ancient woods, the sunny light making all seem indelible and incandescent. And what about that mysterious “Antti Santala”? Who had our grandfather been? When we drove into Lappajärvi, we asked directions to the church, which, again, like many of the churches in Finland, is situated on a hill near the water, with the graveyard around it. This church was also yellow, with a bell tower stuck with the little statue of a man asking for alms for paupers. It was founded in 1737, and is celebrating its 250th anniversary, signs told my mother.

A cursory search of the graveyard and no Änna Kärnä, though there were Kärnäs. No Santalas, though there were Santalas in the Vimpeli graveyard. The act of conception must have happened in Vimpeli. We entered the church, and I signed the guest book. There were three teenagers there, and I asked if anyone could speak English.

“Yes,” a girl said, in perfect American. She was an AFS student from Cleveland, and this was her hostess and her hostess’ boyfriend. The boyfriend said the minister was on vacation and couldn’t be reached, the church office was in the government building (Finland’s church is a state church), and that if we would wait a half hour while he practiced, he would try to find the assistant minister for us. He practiced, and we sat, in the church with stressed-glass opaque windows.

The church in Vimpeli had plain-paned windows so you could see the trees outside waving and moving. We sat on firm, old, light wooden pews, and he made the magnificent pipe organ talk, the sound bouncing off and echoing back. Bach.

We followed him along the unpaved roads of the back neighborhoods of Lappajärvi, to the assistant minister’s house. The assistant minister was at the Rest Home. To the Rest Home. The assistant minister said he didn’t know anything about the graves and he knew the name Kärnä, but not Santala. Reino would know.

Who is Reino? The head gravedigger. The young organist called up Reino, and Reino said he would meet us at the church. He peddled up on his bicycle, and shook our hands with a firm grip, the odor of last night’s whiskey on his person. Reino was in his 70’s, like my mother. I wondered whether she would like to be fixed up with Reino. I liked him. He was solid and firm, like the miners in my home town. She told him our problem.

He took us to all the Kärnä graves, shook his head at Santalas, and nothing was Änna Kärnä. “1933?” he said. He took us down the slanted path to the end of the second-to-last row by the shore of the lake, and pointed. “Here. It must be one of these. These are around that time, July, 1933.” There were two small mossed-over pointed stones on two graves. No names. Paupers’ graves. The graves of dead single poor women.

I snapped a picture. My mother was silent. She wanted to check the church records. “Come back Monday,” Reino said. “The church office will be open. I will meet you here at the graveyard at noon.” It was Friday. What would we do until then? My mother and he talked a little more, and she mentioned one of the names of Änna Kärnä brothers, which she had written down when she talked to her mother.

“Adam?” Reino said. “Adam Kärnä? Sure. I knew Adam Kärnä.” Adam lived over on the island, and had a big farm. His children were called something else, people changed their names, and married, and all. Mother wrote down names, and to the island we went.

There is only a small, about twenty-foot bridge, to the island. No rowboat necessary. We entered the Finnish kingdom of Kärnä. And followed our first directions from Reino. We wound around on a woods road past farms. Lost. We asked a man unloading his pickup truck. Over there, across the main road. We went over to the main road and across it, winding down a long hill.

The place we were looking for was “white,” and “near the lake.” No road led to the lake, that we could see. We turned left, dead end. Up again. Saw some kids on dirt bikes. Mother went out to talk to them. They said, a yellow house, over there and down that road. We asked them to lead us. Followed the kids on the dirt bike. Went to the lady outside hanging her wash. Over there, she said. I took pictures. Down the road. Into a blueberry forest. Woman picking blueberries with a cunning blueberry picker that scoops the berries with tongs, then puts them into a container with a flap. She pointed down the road.

We turned in. Wrong farm. An old man said, “It’s the farm up there, right next to the road, but he’s probably not there, now, staying at his children’s in town, may be back at night.” She knocked at the door. He wasn’t there. Mother tried another name she had.

By this time we were very confused, with all the names and the changes, and wondered what we were doing here, with not even a clear purpose for this search. Why were we searching for Änna Kärnä? Over the main road and up, said the woman with the 2-year-old clinging to her skirts as she picked potatoes. Down the road.

An old woman who looked like my Grandma Ida Kärnä, was walking down the road in her huivi, her sturdy shoes, safety pins pinned to her dress. I flashed a memory of seeing Grandma walking down Third Street in Marquette, about a mile from home, in her late seventies, while I was in college at Northern. I stopped and said, ”Grandma! Mummu! Do you want a ride?” And she laughed at me for even offering such a thing, and talked about how healthy walking is, and scolded me in Finnish. She said I should walk more and not always be in a car. We stopped and asked this lookalike about the names, and gave her a ride to the end of the road.

Up there, she pointed. Laughing. We knew we were the best excitement to come to Kärnä Island today, and that people would be calling each other up and talking about those amerikan-suomalaiset. She knew the name, Antti Santala. Was a schoolteacher, she said.

One ranch house, brick, in potato fields. A young woman, blond children behind her, staring, said her husband’s grandfather would know, at the house around the corner of the road. She said she’d call him while we headed up there. Mother’s command of the language was, of course, necessary, in order for us to be even having this adventure.

Though most students study some English, older people don’t know any, and the students are very shy about speaking. If I had undertaken this search for our roots in these potato fields, I would have been lost a few blueberry patches, cow pastures, and dirt bikes ago.

But I was good for something. I can drive a stick shift like nobody’s business. Spraying dust on the tracked road, we approached the farm. The house was butted right against the road. I stayed in the car while my mother talked to the old gentleman who came out to greet us. As I sat, I noticed lilac bushes, apple trees, the vegetation familiar to me at home in the Upper Peninsula. A cat played in the gravel with a butterfly, tumbling. I wondered how my whiny Siamese cat, Emma Bovary, was doing back in Brooklyn, being looked after by my Greek-immigrant landlady.

A woman in jeans paused to look at me from the barn side door. She disappeared. Soon she reappeared, in a blue coat like a doctor’s coat, a scarf tied around the back of her head. Getting ready to milk the cows. We found out later, at the conference, that Australia has many Finnish immigrants, and when the agricultural representative came to Finland, seeking to get farmers to come to Australia, his last question, after all the willingness from the families to emigrate, was a question to the men,

“Are you willing to milk cows?” he would ask. Most of the men would answer an emphatic “No,” but if a man would hesitantly say, “Yo,” the Australian government would invite the family to emigrate. Milking is women’s work in Finland. When my grandmothers came to America, they changed that custom, and my father and uncles milked.

A man came across the yard with a load of sticks probably for a fire, in his arms. Then my mother gestured for me to come in. I entered a large room with a tile furnace at one end, a sink, a stove, a picnic table in the middle, long runners of rag rugs, a TV, two huge rocking chairs in front of the TV.

McLuhan was right: it is a global village. Television is everywhere. That spring, even in Islamabad, in Dhaka, in Karachi I noticed that video stores were all over, too. During the summer of 1990, in Argentina, when the televisions were blaring the news of the World Cup Soccer victories in Italy to Buenos Aires, where I stood on the pavement outside the appliance stores with the crowds, shouting for the Argentine hero, Diego Maradona, I realized that CNN is the channel of choice all over the world.

Maybe Buckminster Fuller was right, too, that the world will be saved not by governments, but by young businessmen with attaché cases and pin-striped suits, making agreements to promote international commerce. Or cinema.

This room, like others we would see, had many woven wall hangings, täkänäs, and hooked rugs, ryijys, and photographs on the wall. In order to check whether these people in this functional farm house might be our relatives, we went back into the unused living room. They consulted the family Bible, and pointed to a ryijy on the wall that had the family lineage woven into it.

No luck. No mutual recognitions. More names were mentioned, and the old man had a memory of who our people might be. He called them up on the phone. Yes, said the person on the other end. Come on over. The old man said he would come with us and show us the way if I promised to drive him back.

We arrived at another farm, a few hills and dales, potato fields and fertilely cultivated lands away, over dirt roads. A lot of cows. Out came a man called Väino, who resembled my Uncle Arvo. It turned out, it was true; he is my mother’s second cousin twice removed, as we figured it. In the farmyard were the same boys who had led us on their dirt bike to another farm.

They were his grandsons, our cousins, too. Väino pointed to his son’s house just about fifty yards away, across the farm yard. He invited us, and the old man, in. Coffee was served. The wife hovered, washed dishes, served, smiled in friendship, and only at my invitation, sat down with us. The two men and my mother talked Finnish.

The wife and I didn’t say anything. I thought the conversation was going swimmingly. I heard the word sukua a lot, which, by this time, I knew, means “relative.” I thought I was actually following the conversation, though I couldn’t open up my mouth to speak a word of Finnish. But I wasn’t following it all that well, because later my mother told me that the old man and Väino had to be brought back to the topic often, as they really wanted to visit about milk yields and not dead relatives.

Did they have any photos? my mother wanted to know. Väino cursorily searched, and then said, no, someone must have taken the family album. He gave us more names, including one of a cousin a few miles away. Väino gave us what was to be our only description of a living person’s memory of Änna Kärnä. Väino said he had met Änna Kärnä once, when he was eleven, when she was visiting her sister, his aunt. “She was small, like you,” Väino told my mother, “and very, very quiet.”

The old man was restive, and wanted us to bring him back home. I said to my mother to tell them we were going to go to Seinäjoki for the night. “Seinäjoki?” said our cousin Väino. “That’s too far. Stay here.” I didn’t think the invitation was sincere, and my mother hesitated, and went along with me.

Later, in talking about it, we thought his reticence might have been that notorious Finnish reserve, and we might actually have been rude in not staying there at the dairy farm. But how were we to know, being more American than Finnish by now? In the early 1990s, there was a hilarious segment on the television show 60 Minutes, about the Finns and the tango, how the reserved Finns had adopted the tango passionately (or as passionately as such non-emotive types can show) and how they were lining up to take tango lessons or to go to tango parlors.

That show also had a telling—and touching—moment in it, where a modern young Finnish woman said that when cool young Finns play at flirting, they say “I love you” to each other—in English. But when they revert to Finnish—mina sinu rakastaa—“I love you” really means what it means and is not lightly taken.

Not knowing what to do, or whether the invitation was serious or not, we said we had an appointment on Monday at the church with Reino, figuring that if Väino wanted to see more of us, he would be able to find us through Reino. We drove the old man back to his house, headed back to town, and down the 50 or so kilometers to Seinäjoki.

We were hungry, even after all that kahvia, perhaps from nervousness and excitement, and we tried to get a table in a quiet spot of the place. We got a table in the back, but the music was Madonna’s newest hit, loud, and as we ate our local fish dinner (very good), we discussed our search. We wondered who Antti Santala had been.

Had he been the younger man toying with the maid? A traveling schoolteacher, such as they had in those days? An old friend? A rogue? Had Änna gotten pregnant in Lappajärvi, and then come to Vimpeli to be the maid and to have her baby away from the tongues and eyes of her friends and relatives in her hometown?

Had Antti treated her with respect? Was it a one-night stand? My mother recalled the story her mother had told her about seeing her father while she was younger, so at least our great-grandfather was around afterwards. So it must have been impossible for him to marry her. My mother was more kind than I in discussing the morals of the man, wanting to give him the benefit of the doubt. I wanted to make him a heartless rogue, or as in a Finnish folk song we knew, a hulivili poika, a wild boy, sowing his wild oats. My rakish great-grandfather.

Saturday morning in Seinäjoki. We had in mind to spend the weekend searching for my father’s side of the family, but were hesitant how to proceed. We didn’t even know what we were trying to find. So we went shopping. Across the street, the Sokos chain department store.

Soon my mother got lost in the book section, laboriously translating titles. I found a book about Finland in English, and read the whole thing while my mother performed her concentrated and oblivious dawdling that has amused and frustrated our family all our lives.

I was reminded that Finland has fought three wars since independence in 1917, and they had over seventy years as an independent country, that the wars had been devastating, that hundreds of thousands of young men had died, and I remembered the two cemeteries we had visited, with their special sections for war dead, row after row of young men with the same birth year and death year.

I read about World War I, and the Winter War in the late 1930’s with Russia, and about the German retreat from Norway down through Finnish Lapland during World War II. I remembered a picture book, at my aunt’s house, in Finnish words I couldn’t understand, with brown photographs of men in white suits on skis, sniping Russians from behind trees when the men came out to pee in the morning.

I remembered the last movement of Sibelius’ Fifth Symphony, with those soaring octaves that somehow move me to tears, which Sibelius composed during the last battles of World War I. Mannerheim’s name was mentioned a lot. As many men had died as those of our grandparents who had emigrated earlier in the century.

All disappeared from the country of about four million; two generations were decimated, significant in such a population. Many of those who emigrated earlier in the century, left after refusing conscription into the Russian army. Finns for a long time called those who emigrated, cowards, deserting the homeland when things were tough, and it is only recently that they have begun to feel friendly to the emigrants. The author said that Finland has the fastest-growing economy in Europe, and proudly recounted that Finland is about the only country that repaid its war debt to the United States.

An hour or so later, my mother was ready to really shop, and we went upstairs to the domestics section, and bought linens and towels and tablecloths for gifts. The Iitala glass section, the Arabia china section, the Marimekko linens section, all available in America, beckoned us, as well as the Aarika wooden jewelry, the local brands.

Finland is very expensive, and we felt it as we spent our marks in ethnic pride in the beautiful Finnish designer merchandise. Someone later told us that the Finns aren’t such good designers now they’ve gotten comfortable.

Monday and back at noon in Lappajärvi. No Reino. We had spent a happy morning on the road from Vasa, the city on the Gulf of Bothnia with much Swedish influence, eating sweet peas and throwing the shells merrily out the window, sucking on strawberries we had bought from the market square.

We felt a little forlorn as we walked the graveyard of the yellow church on the bluff by the lake, searching again for Änna Kärnä. No Reino and what were we to do? The church secretary. I remembered the way and drove there. By now it was l P.M., and we went into the municipal building.

Upstairs, my mother was talking with the secretary, who was saying she didn’t have much time, she was alone here trying to answer the phone as well as take care of city records, and everyone was on vacation. Besides, she was about to get off now. I said in my best savvy New York voice, “Pay her and I’ll bet she’ll find the information.”

My mother said we would have to come back tomorrow. Tomorrow? And where would we stay? The secretary said there were no hotels or motels in the area, but there was a campground with cabins. We followed her directions and arrived there. I was ill-humored, and my mother was disappointed.

Another day looking at graveyards and searching for what? Would we ever find Änna Kärnä? We were lucky that someone was there at the campground. Though we didn’t realize it, for it was only August 17, the season had ended. Children were beginning school this week. Families had ended their vacations.

We were shown a cabin that cost 200 marks, cheap for Finland. It had a fireplace, a sauna, a front porch with water to look out on over the distance, a little kitchen, and two bedrooms. We took it, and went up to town, about eight kilometers away, and bought some food at the local supermarket.

My mother got delayed at the bread, and then at the dry cereal, reading the ingredients on the labels, for she belongs to the natural food co-op in Ishpeming, and I gagged as I passed the blood sausage with memories of my father’s penchant for it, settling on some Karelian pies, some cold cuts and some cheese.

The new potatoes looked good, so we took some of those. Cucumbers. Tomatoes. Some fake wine that when I drank it, gave me the worst headache I have ever had. Liquor, wine, and full-strength beer are sold only in government stores. Drunk-driving laws in Finland are so strict that there are hardly any alcohol-related accidents.

Back at the cabins, my mother said we should try to find the other cousin Cousin Väino had mentioned. My mother didn’t seem to want to go back and visit Cousin Väino at his dairy farm. My mother had asked the church secretary where the cousin lived.

Her name was Aila Koivisto. So we drove again, searching for “a gray house just by the side of the road, you can’t miss it.” As before, we took the wrong road, ending up on a logging road in the woods. When we finally found the right road, we went right past the house because it didn’t look like a house, it looked like a weathered barn.

When we finally knocked on the door, unannounced, we were invited in by a woman who looked older than she was. Aila Koivisto had never married, and worked for years in a nearby town in a factory, until the factory closed. Now 59, she had come back to the Lappajärvi/Kärnä area where she had been born, both parents now dead, and only a few distant cousins around, with whom she didn’t socialize, because she was not as well off as they. She lived in her parents’ tupa, or cottage by the lake, though it was about a quarter mile from the lake, and right on the road, as described.

Inside, Aila lived in one room that contained a wood stove, a table, a narrow bed, a sewing machine with a doily, some chests, a sink, a refrigerator, and the omnipresent African violets, doing very well, thank you. She offered us kahvia and for the pulla took out some frozen rye bread and rolls which she thawed in the oven.

The freezer was full. She had attended a concert two nights before, a choir from Sudbury, Canada, from the Finnish Lutheran church. My first and only trip to Finland had been as a member of the Suomi College Choir, in the summer of 1963, when we had toured all of Finland as the official choir of the Lutheran World Federation which was held in Helsinki that year.

My mother and Aila talked and I assumed my role as the silent daughter, speechless observer. Aila had a beautiful thick bun on the back of her head, grey with streaks of blond. Her hair must have been long and beautiful, archetypically blonde and Scandinavian, and in fact, when people had described her to my mother, they had said “Aila has a big bun on her head.” When she moved, she moved with litheness and a female grace that would be provocative, and probably had been. Single, childless, sexy.

A survivor in a nation where her whole generation of men had been slaughtered. A factory worker retired and now living out her life on her country’s democratic socialist pension in a small drafty house in a small rural town, going to church and to choir concerts on her bicycle, or on the bus.

Aila pulled out an old photo album. My mother was asking everyone we met for a chance to see old photographs, hungry for a glimpse of her grandmother. There were none of Änna Kärnä, though there were many of Liisa, Aila’s mother, Änna Kärnä’s niece, when she had been a servant girl in Manhattan for eleven years until she had come back home for a visit, met Aila’s father, and fallen in love.

Aila’s mother, though she knew English, had not taught Aila, but had come back and seamlessly reassumed her rural ways. Immigrant girls all sent photographs back home of themselves attired in fashionable hats and dresses, urban magazine plates, as if to tell the people back home how well they were doing in the new land. This album was full of such photographs, of Liisa and her friends. Liisa had worked on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, a few blocks from the school where I was a principal.

So Änna continued to remain a mystery to us. As we drove back to the cabin, we were silent, thinking about our cousins and their lives here in Lappajärvi. That evening, we wandered the paths near our cabin. No blueberries. The lake. A sauna. Postcards. A fire in the fireplace. Early to bed. Early to rise in order to get to the church office on time.

I decided to walk, and my mother took the car up there. My walk along the lake and the road with my notebook, and the wildflowers the same as back home in the U.P.—foxglove, Queen Anne’s lace, chicory, goldenrod, and those strange gray crows—brought peace. I felt at home here. A cow in the meadow mooed at me.

The way the carpenters lapped wood on the barns was similar to barns still standing in the immigrants’ new homeland in the Upper Peninsula, a pattern brought over and made part of my visual understanding of how barns should be built, just as were the patterns in the sweaters and mittens we saw being knit by women standing in the markets, similar to those my grandmothers had knit.

In fact, several of the barns in Cleveland Location, up our alley, the Ojanens’ and the Juholas’, were similar. The crafts of the immigrants’ hands lived longer than they did. And Änna Kärnä lived only in the fleeting memory of Väino when he was an eleven year old boy.

Up at the church office, my mother had the information. Änna Kärnä had, indeed, been buried in this cemetery in July, 1933. In a family plot. She also had the names of forebears for another century or two, though it was very difficult to read the ones dating back to the early 1600’s. We went back up to the church again and walked the paths, searching.

Finally we came to that row where Reino had pointed out the two small pointed stones on two graves in 1933, and my mother resignedly took a picture of the stones. This must be her grave, all right.

“I’ve been thinking,” my mother said to me, as we sat sweating in the sauna, throwing water on the rocks. We’ve always had important talks in the sauna, and this was to be one: I could tell by the tone of her voice. “I think we should buy Grandma a headstone. It’s a disgrace that she doesn’t even have a headstone.”

I sat silently, and knew that this was probably the reason for her being so impelled. Something was telling her to come and make things right. Grandma Änna Kärnä was sending her a message. Come to Finland and validate that she had lived and died and given birth to some Americans.

“I agree,” I said. “Let’s do it. How much does a headstone cost? I’ve got American Express, if they’ll take it. I’ve got enough room on my Visa, too.” We went to bed and slept a good sleep. After breakfast, hot chocolate and cheese, my mother told me what she had been thinking of in her dreams. She wanted to make sure that one of those graves was in fact Änna Kärnä’s, so we would go and get Aila, because Aila knows the ways of the town.

Then we would go up to the church office again, and find out the number of the grave plot. When we arrived on Aila’s doorstep at 9:30 A.M., Aila didn’t even look surprised. She said to give her a few minutes to change clothes, and she would be glad to come with us. Aila and my mother went up to the church office. They came down, and said they had called Reino, and they had the exact number of the plot: 192.

Reino came bicycling up, and we began to walk down the paths of the church yard. It was a cold and blustery morning and we were shivering in the wind. Reino didn’t know which one was 192, so he went into the church. A few minutes later, two handsome young men arrived wearing rubber boots.

The city engineers were on the premises. They had with them a large scroll, and as I peeked over their shoulders, I saw them pointing to 192. Then we all trooped behind them, to the opposite side of the cemetery from the 1933 grave we had thought was our grandmother’s. Next to a thick, short, stone wall, beneath a birch tree, there was a pause in the lineup of headstones.

“There.” The man pointed. “There.” In a family plot. But not of Kärnäs, Koivistos or Rautalahtis. Of Hytinens.

No one we had met had even referred to Hytinens as relatives. I thought of the Hytinens I had known growing up in Ishpeming, Michigan. Were they my cousins?

We had found Änna Kärnä’s grave. The yellowed scroll of the map of the church even had her name written there. I saw it. “Änna Kärnä.” It was unmarked. No one had bought her a stone. And so we did. Reino said he would do it, and he wrote down the words we had thought to put on it.

“Äiti” (Mother). “Änna Kärnä” December l9, 1854-July 15, 1933.”

We went to the bank and bought a cashier’s check and put the check in Reino’s hands. Aila said she would get hold of a camera and take a picture of it. We were free to go. My mother’s search, my search, was over. The picture arrived a few months later, along with Aila’s Christmas card. We plan to go back, to find Antti, that wild and irresponsible great-grandfather who played horseyback with my grandmother on his foot, kicking her all the way to Michigan.

END

The Lord’s Prayer

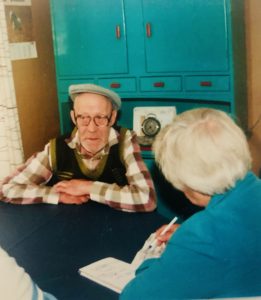

Anna Karna’s grave and gravestone.