Here is a 2018 interview with me published in the journal, Gifted Education International.

Sansom, S., Barnes, B., Carrizales, J., & Shaughnessy, M. F. (2018). A reflective conversation with Jane Piirto. Gifted Education International,34 (1), 96-111. DOI: 10.1177/0261429416650950

A Reflective Conversation with Jane Piirto

Shyanne Sansom

Bryan Barnes

Jason Carrizales

Michael F. Shaughnessy

Eastern New Mexico University

1. First of all, what are you currently working on, researching, writing?

Piirto: In the last few months I published four chapters, one on creative writers for a journal in Poland, edited by Wsielaw Limont; another “Poems in Service of Service,[i]and another called “The Five Core Attitudes And Seven I’s For Enhancing Creativity In The Classroom.” [ii] The fourth is called “The Creative Intelligence of Teachers Resisting the Pearsonizing of Global Education.” [iii]In press is a chapter called “The Creative Process in Writers. ‘.[iv] I just presented that study at the 15th European Council for High Ability Conference in Vienna in March, 2016, and I have two presentations accepted for the National Association for Gifted Children annual meeting in Orlando, Florida in November, 2016.

I am still sitting on mountains of data from personality assessments I conducted over 19 summers (1989 to 2009) from Ohio Summer Honors Institutes for talented teenagers, which our university was granted, and I am working on a study called “Six Ways of Looking at the Personalities of Talented Adolescents.” Another project involves a study of personalities of teachers of the gifted and talented for which I have been collecting data for years.

I do a fair amount of peer reviewing and have been the external reader of several dissertations from other nations and universities and in other disciplines (the present one for a candidate who’s a monk writing on creativity and visual arts). Of course, one never knows what project proposal will come in an email.

A long-term ambition of mine would be to write multiple books for each of the domains in the second part of Understanding Creativity. I have already written one book on creative writers, and I’m working on gathering biographical data from ten North American women visual artists, for a book that utilizes my Piirto Pyramid of Talent Development, as the theoretical framework.

I am at a small liberal arts university and so I teach a full 12 hour load each semester, and that takes up a lot of time. There are no graduate assistants at our university, except in the athletics deparment.

2. How do the 5 dimensions of overexcitability relate to ADHD? Are students identified as gifted and talented more likely to receive a diagnosis of ADHD?

Piirto:

I am not an expert on Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. I typically refer people to the wonderful 2005 book that James Webb, Edward Amend, Nadine Webb, James Goerss, P. Veljan, and Richard Olenchak published, Misdiagnosis and Dual Diagnoses of Gifted Children and Adults: ADHD, Bipolar, OCD, Asperger’s, Depression, and Other Disorders. I know nothing about the overexcitabilities and their relationship to ADHD.

3. In what way can teachers capture this overexcitability and intensity in gifted students and use it to enhance their learning and creativity?

“Whether or not the gifted have more intensity has not been conclusively proven, but seems to be an artifact of the essentialist philosophy that the gifted are more intense, propounded by some in our field”

Piirto: I published a comparison study in 2012, one of the only comparison studies in the literature, that compared identified gifted high school students with high school students who attended a vocational high school.[v] The study showed (a) Differences among the Psychomotor, Sensual, and Emotional Overexcitability (OE) means were not statistically significant, and (b) the Imaginational and Intellectual OE means of the gifted male students were significantly higher than the means of the vocational female students, vocational male students, and gifted female students. The effect sizes were classified as large. I didn’t find any differences in OEs by gender.

“I am of the persuasion that the overexcitabilities in Dabrowski’s theory have been overrated and misinterpreted.”

Piirto: As I said in my article, “21 Years with the Dabrowski Theory: An Autoethnography” (Advanced Development Journal, 2010),[vi] I have diversified, moved on in terms of personality assessment, utilizing other instruments with talented teenagers. My goal is to confirm or disprove the presence of personality attributes in my theoretical framework, the Piirto Pyramid of Talent Development. But people in our field should be careful about assuming that the gifted students are more sensitive than other students. This just hasn’t been proved.

5. Are overexcitability quotients, OEQ’s, being used in addition to or as an alternative to traditional testing to identify minorities for gifted and talented programs?

Piirto: OEQ stands for the Overexcitability Questionnaire (OEQ).

“I am of the opinion that there is no such thing as an overexcitability quotient, and that one should never use the OEQ or the OEQ II to identify minorities or ANYONE for gifted and talented programs, only to describe.”

Piirto: My articles about the Dabrowski theory are on my website, and on ResearchGate (www.researchgate.net) and on BEPress(www.bepress.com).

My articles are downloadable and readable on these sites. I get a monthly report on how many reads and downloads there have been, and I’m always surprised at how far my work has reached.

6. What is the most important thing for regular classroom teachers to know about their gifted students?

“The most useful definition of giftedness is precocity.”

Piirto: Gifted students are precocious in their areas of talent. They exhibit the characteristics of older students in whichever domain they have talent. This is an easy way to recognize talent: young talented readers read more and deeper; young mathematicians can do problems that older children can do, etc.

7. How do gifted programs focus on a student’s individual strengths?

Piirto: There are many ways. If you are going to focus on individual strengths, a useful and convenient way is to focus on their interests, perhaps using the Renzulli model.

Students reveal who they are if you look carefully enough. Again, precocity is the clue to discovering talent. Many of these students show these talents outside of the school setting, so the community and culture and the home must be involved.

8. Where is thinking on gifted education headed? Who are the new leaders?

Piirto: In the U.S., we grow our leaders within the National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC) networks and in the American Educational Research Association (AERA) Special Interest Group (SIG) on Research on Giftedness, Creativity and Talent. The American Psychological Association (APA) also has young leaders who are psychologists who have studied giftedness and talent. These are our Young Turks. They are very well trained and proficient in statistical and theoretical methodologies. They are less prone to believe in common gifted ideologies. I respect them highly.

9. You have researched gifted education in other countries. How does it compare to gifted education in the United States?

Piirto: I have published research on indigenous schools for the talented in India, the Jnana Prabhodini School in Pune, and the Krishnamurti School in Chennai.[vii] The Jnana Prabhodini school has a philosophy that is based on that of a guru, as does the Krishnamurti school. The Prabhodini school, however, uses common standardized western tests to identify talent, where the Krishnamurti school eschews such.[viii] These are private schools. Giftedness in public schools in India is developed based on the British model, an artifact of the Raj. Education of the gifted in the U.S. takes place in both private and public schools, but public school education is more problematic, given the difficulty of providing individual assessment, as is provided for other special needs students by federal decree. The presence of poverty is a confounding factor.

10. You have been involved in a wide range of fields throughout your career. How have these diverse interests influenced your thought on gifted education?

Piirto: I have not really been involved in a “wide range of fields.” I have, however, been involved in the field of literature, specifically as a writer of poetry and fiction. This has influenced my thought process in that I can empathize emotionally and understand just how difficult it is to achieve recognition or respect in various domains. It is much more difficult to get published in literary fields than in the field of the education of the gifted and talented.

The constant disappointment of experiencing rejection is alive and this has affected my work on talent in domains, specifically on the existence of elite gatekeepers, who are the critics, judges, agents, and the ones who permit the creator to participate in the highest levels of the field.

My proudest accomplishments are not my awards in gifted education (e.g., Mensa Lifetime Achievement Award, NAGC Distinguished Scholar and Torrance Creativity Award), but my inclusion in the U.S. Directory of Poets and Writers, which has very strict listing requirements.

I have also included these standards within my own research on creative writers. To be listed, a person must have a minimum of 12 points of accumulated credits: for example, one published poem counts as one point; a novel counts as 12 points; a book of published poetry counts as 12 points; and an established literary award counts as 4 points. In 2016 there were 10,602 writers listed (http://www.pw.org/directory/featured), or about .000033 of the population of the United States (323,553,345 on April 6, 2016). Being listed is voluntary. I have qualified as both a poet and a writer, having published fiction, creative nonfiction, and poetry. Yet I still struggle with envy and a feeling of insufficiency in the field of creative writing. Some of my literary books are published on Kindle, but no one reads them, and more people know of my scholarly work in giftedness and creativity studies than of my literary work.

11. In your journal article about the Piirto Pyramid, you mention the “sun” of gender as being an important factor in the development of creativity. Has there been any research done on the effect of gender on talent development in individuals who are gifted and talented?

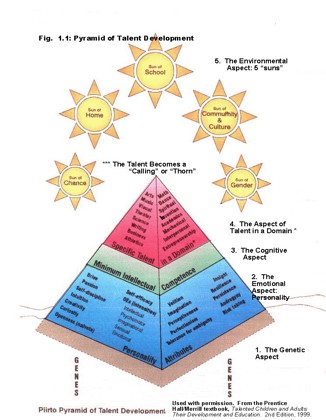

Piirto: I wrote that there are five environmental influences on all people, including the talented. These are environmental “suns” of Home, School, and Community and Culture, the most apparent. The other two “suns” are of Chance and of Gender.

“As far as I am aware, the Piirto Pyramid is the only talent development model with gender as an environmental factor.”

a. Piirto Pyramid of Talent Development

12. In your opinion, what are the worst misconceptions about individuals who are gifted and talented?

“A pet peeve is the assertion that these are “our future leaders.” That is an argument made by people who are using a geopolitical and nationalistic reason to educate the gifted and talented.”

Piirto: I have thought long and hard about it, and I carefully phrased a belief about giftedness in Talented Children and Adults:

“My own philosophical position is that the “gifted,” for the purposes of the schools, are those individuals who by way of learning characteristics such as superior memory, observational powers, curiosity, creativity, and the ability to learn school-related subject matters rapidly and accurately with a minimum of drill and repetition, have a right to an education that is differentiated according to these characteristics. All children have a right to be educated according to their needs. These academically talented children become apparent early and should be served throughout their educational lives, from preschool through college.

ii. “They may or may not become producers of knowledge or makers of novelty, but their education should be such that it would give them background to become adults who do produce knowledge or make new artistic and social products. These children can be found in all socioeconomic and ethnic groups by those who look hard enough. Standardized testing is a good way to find them but not the only way, especially for disadvantaged groups where observation, portfolio assessment, and other methods should be utilized.

iii. “These children have no greater obligation than any other children to be future leaders or world class geniuses. They should just be given a chance to be themselves, children who might like to classify their collections of baseball cards by the middle initials of the players, or who might like to spend endless afternoon hours in dreamy reading of novels, and to have an education that appreciates and serves these behaviors. This education should be focused on developing children’s proclivities in certain domains of achievement. The child who is a dreamy reader of many novels will perhaps become a novelist or poet; the baseball card collector and reader of nonfiction may perhaps become a scientist.” (Talented Children and Adults, 2007, p.37).

Another pet peeve of a misconception is the failure of thinkers and writers to realize that giftedness is a social construct, dependent on the society or region in which the talent is valued and recognized.”

Piirto: There are handouts that you find in many introductory workshops. My students bring them back all the time. The handout has two columns: “The high achiever is . . . “ “The gifted is . . .” If you look at the “high achiever” column, you see the behaviors that we value in many gifted students, and the derision for “mere” achievement is apparent, where those who are “gifted” are supposed to be very rebellious, insightful, weird, and such. That is not true. For example, our modern society no longer values talent in the domain of hunting for game animals as compared to the past. Talented hunters were necessary in the past, to provide food for the people. Now hunting is a sport practiced by talented hunters, but they are only recognized within their very narrow groups. Our world does not need its hunters as it did in times of yore, yet hunters continue to be born. The social construct for the value of the hunter to society has changed. I could go on, but these two are my most hated misconceptions.

13. What has surprised you most in your research and work with individuals who are gifted and talented?

In my research, what has surprised me most is that the biographical patterns by domain that I deduced in researching the first editions of Understanding Those Who Create (1992)[xi] and in Talented Children and Adults (1994)[xii] have held up.”

Piirto: I remember calling up a friend while writing UTWC, and saying, “I’m finding out that a lot of ballet dancers had eating disorders.” I have asked my graduate students, in their biographical studies—they have to do an in-depth study of a person talented within a domain (writing, visual arts, science, mathematics, invention, entrepreneurship, popular music, classical music, acting, athletics), and compare and contrast the themes in that person’s life with what I wrote, using the Piirto Pyramid as a framework. “Prove me wrong,” I challenge them. They are surprised also, that the themes by domain seem to be more robust than not. Hundreds of my graduate students’ studies have confirmed these themes. I am surprised and pleased. Here is an example of a chart which I ask them to include their biographical study and compared their individual findings with what I proposed in the chapter on the domain of their individual contribution. This was a study of actor Cary Grant by my student Joe Hug.

Cary Grant By Joe Hug | ||

Piirto Pyramid | What Understanding Creativity says about Physical Performers (Actors) | Cary Grant |

Genetic Aspect | – Often come from theatrical families. | – Working class father who was considered extremely handsome. – Grant was the youngest (of two) children. – Father battled with alcoholism. |

Emotional Aspect | ENFJ (Extraversion, Intuition, Feeling and Judging) Intuition with Extraversion – Change Agents – Broad Interests – Like New Relationships Feeling and Judgment – Use Feeling(s) in the behavior they outwardly exhibit. – Observant – Resilience – Tolerance of Ambiguity | – Moved from relationship to relationship. (Both Male and Female) – “Divorced” 5 times. (This includes his divorce from Randolph Scott) – Grant carefully observed others, noticing their every movement and gesture; copying those he liked. – Grant exhibited noticeable perfectionism. – Grant openly displayed his feelings. He would move back and forth from being happy to then either depressed or angry. (Emotional Push-Pull) – Exhibited Suicidal Ideation/ 1 Attempt – Treated for Depression using LSD. |

Cognitive Aspect | – Bodily Kinesthetic Intelligence (Spatial) -Interpersonal Intelligence -Intrapersonal Intelligence -Active Memories | – Social Recluse: Would often retreat, to the confines of his home, a hotel room he was staying in etc. – Co-Dependent with both friends and wives. |

Passion for the Domain: | – Obsessed with their Work – Motivated by Money | – Broke iron-clad contract system to make more money on a per film basis. (Paved the way for many others.) – Measured self-worth by how much money he made/had. (Worth an estimated 60 million when he died.) – Motivated by money Grant expanded his performing to include radio and continued for some 20 years. – Used work as an escape from life. (When in times of recluse he would only leave to go to the studio.) – Career spanned 72 films. – Proclaimed retirement multiple times, but each time a film opportunity came that he couldn’t pass up. (Ex: Notorious, Alfred Hitchcock) – Following his film career and another period of seclusion he put together a 90 minute, one man show and toured extensively. |

Piirto: In my work with talented individuals, especially the thousands of identified gifted high school students who attended our summer honors institutes for 19 years, and the thousands of elementary students for which I was principal at Hunter College Elementary School in NYC in the 1980s,

“I have been struck with the human need for community. Just like all people, the talented students thrive when they are “seen” and understood by like-minded individuals. This has confirmed my support for self-contained classroom academic options for these students.”

They formed life-long friendships in this elementary school and in these summer honors institutes, and count their experiences with each other as essential for their emotional growth and wellbeing.

14. Why is it important to “ understand creativity “ or the creative person?

“As an educator, I have to believe that creativity can be taught.”

By understanding the patterns in creative lives, by looking at biographical accounts of the creative process in creators, I have been able to reconstruct it and to create exercise and lessons that mimic the creative process in creators. I described these exercises in great depth in my practical book, Creativity for 21st Century Skills: How to Embed Creativity Into the Curriculum (2011, Sense Publishers)[xiii].

Piirto: I’m a bit rebellious, and as an intellectual, I am bored with the omnipresent Guilfordian divergent production exercises that are touted as enhancing creativity, even now, 60 years later, so I have tried to update and expand the repertoire of lessons and attitudes that teachers can use in enhancing creativity.

15. What are your five “ I “’s and have they changed over the years- with the advent of the Internet?

Piirto: The Internet has nothing to do with it; why should it? Creativity for 21st Century Skills is a book that focuses on the practical applications of a theoretical approach to creativity training I have developed (Chapters 2 and 12 from Understanding Creativity expanded). If creativity can be taught, then paying attention to one’s creative process can help one to be more creative and thus, to teach others to be creative. This approach has been derived from information in biographies, memoirs, autobiographies, and interviews. The book describes what many creative people really do in their personal creative processes. It may be helpful for those seeking to develop 21st Century Skills of creativity.

“Five Core Attitudes (Openness to Experience, Risk-taking, Self-Discipline, Tolerance for Ambiguity, and Group Trust), Seven I’s (Inspiration, Intuition, Improvisation, Imagination, Imagery, Incubation, and Insight), the General Practices of ritual, meditation, solitude, exercise, silence, and a creative attitude to the process of life, with corresponding activities, are described, discussed, and illustrated.”

Here’s an example of one of the I’s, imagery, a section of Chapter 4 of Creativity for 21st Century Skills (2011).

THE “I” OF IMAGERY (pp. 89-93 of Creativity for 21st Century Skills. Used with permission of the author.)

Imagery is also part of the creative process. The term imagery is psychological, the ability to mentally represent imagined or previously perceived objects accurately and vividly. Imagery is an attribute of imagination. Imagery is not only visual, but also auditory, tactile, olfactory, and gustatory. Three types of studies of creativity and imagery have been done; (1) biographical and anecdotal studies of creators telling about their personal imagery and how it inspired them; (2) studies which compared people’s ability to create imagery and their scores on certain tests of creative potential; and (3) studies about creative imagery and creative productivity.[xiv]

Imagery is so natural to people that it almost goes without noticing. Take the creation of metaphors. Metaphors abound in human speech and writing. In fact, all metaphors are images for what is signified, helping people to see things better. A whole science of metaphor exists, which is too arcane to go into here, but the reader can notice metaphor in any magazine or television advertisement. Metaphor is the very way we see life, one may argue.

Advertising creators have great skill in this; the image of the bored Maytag repairman has been implanted in a society’s psyche so that one just knows that Maytags don’t need servicing very often. The image of the rough, tough, craggy man on a horse is associated with the Marlboro cigarette that hangs out of his mouth. The black and white photographs of languid anorexic European-looking teenagers with drug habits lounging around on the beach is the image of Calvin Klein for Americans who are not so slim, not so bored, and not so vacant. The image of singing fish on the wall ordering the man to give him back his filet of fish raised fish sandwich sales at McDonald’s. The old lady asking “Where’s the beef?” did the same at Wendy’s. People watch the Super Bowl for advertising images. Babies talking about trading stocks from their high chairs and cowboys herding cats attract as many viewers as are attracted to football.

Creating an image that functions as a metaphor in words is what creative writers do. The words signify images and the skillful writer chooses the proper words or combinations of words to do the signifying. Read the various shades of white named in your local paint store: “pure white,” “Zurich white,” “rhinestone,” “off white,” “Navajo white,” “ambience white,” “city loft,” “minimal white,” “light moves,” “white wool,” “antique white,” “Bauhaus buff,” “nostalgia white,” or “aria ivory,” which do you see through the words chosen by the writers who named these shades? The adjectival metaphors, the nouns associated with shades of white bounce off the recognition of the reader. Which do you want on your walls? Or of green: “gallery green,” “Majorca green,” “acanthus,” “Regina mist,” “bayberry,” or “billiard green”? You say you can’t tell until you see the variations of shades; the written and the visual are here combined and the choice is often agonizing to the fussy decorator. The name of the shade doesn’t matter, but yet it does. The evocation of image through words are illustrated within these examples.

Examples from Creators of the “I” of Imagery

Darwin saw evolution as the image of a branching tree; Einstein pictured what it would be like to fly next to a beam of light: “If a person could run after a light wave with the same speed as light you would have a wave arrangement which could be completely independent of time.” Einstein learned to make visual thought experiments in his high school at Arau, which was run on the Pestalozzi theories that “Visual understanding is the essential and only true means of teaching how to judge things correctly.”

Architect Maya Lin, who won the competition for the design of the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, DC when she was still in college, deliberately tries not to create an image when she is working on an idea. That is because imagery is so powerful. She argues that creating an image immediately might lead to a sort of premature closure. She said, “In anything I’ve done, what I will do is resist picking up a pen, except to write, for as long as I can. And what I want to do is try to understand what I want to do as an idea.” She researches about the site—its history, its culture—before creating the image. “I try to think of a work as an idea without a shape. If I find the shape too soon—especially for the memorials, which have a function—then I might be predetermining a form and then stuffing the function into the form.”

Guided imagery training goes on in schools, in athletics, and in business and industry. This training attempts to help people learn to manipulate images in their minds. The 2010 Winter Olympics television coverage showed skiers such as gold medal winners Lindsay Vonn and Bode Miller with eyes closed, imaging the course they were about to ski. In guided imagery a leader reads a script, with pauses, that suggests images to the people in the group, who sit in a receptive manner, quietly, with eyes closed. Imagery is essentially spatial, and as such, concrete evidence of the mind’s power to construct. Coaches teach athletes to image their performances before they do them; they visualize the ski run, the football play, or the course for the marathon. Studies have shown that athletes who use imagery perform better.

Exercise for a Group or for Staff Development

In a creativity group, members experience an example of guided imagery. Group members then think of ways they could use imagery in their own practice (see Table 3.1). One wrote, “I love the imagery of exercise. It feels so real, it helps to create so much in my mind. It also makes me feel so calm and centered. I also like closing my eyes. Using the mind’s eye is a great skill. I think we should all develop the ability to create in our heads.” The group does an exercise called “Ten Minute Movie,” in which group members, of two or three are randomly given a time and a place, and they must create a storyboard for a movie based in that time and place.

Exercises for an Individual

Practice creating images from thoughts. You may use similes (this is like . . . ) or metaphors (this is . . .). Draw them or write them in your Thoughtlog

Mentally image a lemon. Now mentally suck it. Feel the juices in your cheeks spurt. This is gustatory imagery. Draw it or write a poem about it.

Mentally image the smell of your favorite flower. Feel the smile in the nose. This is olfactory imagery. Draw it or sing a song about it.

Mentally image touching the soft fur of your favorite pet or mentally stroke the cheek of your newborn baby. This is tactile imagery. Draw it or dance about it. -Mentally image yourself winning a race in your favorite sport. Take yourself through the whole process, in all the moves. This combines visual imagery with tactile imagery. Make a flowchart.

–Mentally image the voice of your mother, father, or favorite teacher saying one of his/her famous sayings. This is auditory imagery. Imitate her.

Ways Teachers Can Embed the “I” of Imagery into Their Curricula

Here are some ways that teachers can use imagery to enrich their classroom curricula. These are suggestions by teachers from the creativity groups.

Table 3.1. Ways Teachers Can Embed the “I” of Imagery

Ways Teachers Can Embed the “I” of Imagery Into Their Classrooms General ü Students create their own images for things they need to remember. ü Have students image themselves completing a goal or obstacle. Visualize what it would like and feel like to achieve that. ü When students are too wound up, help them find their “inner” adult by asking them to visualize themselves in the future. Social Studies ü Imagery could be used to set the stage for an event in history. Students would close their eyes and listen as the teacher painted a word picture of the scene. Descriptions of the place, the people, the emotion, the action give a clear sense of what it was like to be there. ü Students would be given the name and description of a character they will play in a dramatic representation of the event in time. They will imagine themselves as the character and “act” accordingly. ü Before reading Susan B. Anthony speech, “Are Women Persons,” create an imagery exercise about women and men coming to hear her speak. Maybe a woman with her child in arms. Jeers in the background. Loud noise. Posters on both sides of issue. After giving a chance to imagine setting, I will read the speech. Language Arts ü As a pre-writing exercise, they could make drawings, not using any words until the images were all released from their minds. ü Assign a writing exercise requiring students to write descriptions of images, without transitions or paragraphs, around the theme of a journey or a dream. ü Students always write better and more naturally after the teacher shows them video excerpts concerning the historical facts and commentary from the time and place that we are studying. This is partly due to them acquiring background knowledge, but more because the images in the film connect with the images in their own minds and blend to form new images in their writing. ü Use paintings and other artworks as writing prompts. Visual images transform and become written images. ü Use imagery before beginning a literary unit. With Great Expectations, my students close their eyes and I take them on a trip to the graveyard. Pip is alone, meets the convict. ü Poetry: Students close their eyes and listen to a poem. Have them draw or write down images. ü Discuss the importance of visualizing scenes from what you’re reading to deepen understanding. Mathematics ü Forming the semi-regular polyhedra from the regular polyhedra; imagine the truncation of the vertices – see the new faces. Use images to predict and then concretely verify those images. Science ü Use imagery when studying bees. By using cups with different scents the students will explore how bees use their senses to find the pollen that needs to be collected. By using their sense of hearing, students will listen to the flight of the bumblebee to imagine the sounds of a busy bee hive. ü Use imagery as anticipatory set to understand different processes–water cycle, food chain, flow of electricity; history, health (Magic School Bus series). Music ü Play evocative music and have them draw pictures while the music is playing, or tell stories about what images the music made them think of. Art ü Setting a scene is a great way to make students think visually. Take turns describing a place while the other students draw that place. ü Students close eyes and imagine their own “happy place”–have them create the place in a picture (through art) |

=====================================

16. Domains of passion—I love this phrase- tell us about these domains of passion.

Piirto: The term “domain” is a common term in creativity circles. I particularly recommend the creativity research framework proposed by Feldman, Csikszentmihalyi and Gardner in 1994 in their Changing the world: A Framework For The Study Of Creativity. A domain is “the formally organized body of knowledge that is associated with a given field” (p. 20). They proposed that creativity research takes into account the domain, its field, and the individual’s interaction with it. A domain is within a field (for example, the domain of poetry within the field of literature). An individual develops an interest that must become a passion in order for him or her to want to work in a domain. Passion is included because creativity needs motivation; a person has to want to be creative, and often the person can’t not do the work and study needed to master the domain. Thus the new “I” of creativity I am thinking of including as the eighth “I” is Intentionality. You aren’t creative in a domain unless you intend to be.

17. What are some different approaches to enhancing and developing creativity?

Piirto: That’s a topic for a book, not an interview. See Understanding Creativity, and Chapter 4 in my textbook, Talented Children and Adults (3rd edition, Prufrock, 2007).

18. Who has mentored you or influenced you?

Piirto: I was mentored early on, in the late 1970s, by Mary Meeker, who made me one of the Structure of Intellect Learning Ability program’s first advanced trainers. [xv]I traveled the country giving SOI workshops. I stopped doing that in the mid-1980s when I found that the test had marginal validity, and that the ceiling was too low for gifted students. But that work led me to seek alternatives to the IQ assessment. I have been influenced by the work of the Institute of Personality Assessment and Research (IPAR) in the 1950s, by the work of Bloom (Developing Talent in Young People, 1985). I worked with Rena Subotnik at Hunter College in the 1980s and we still are friends. Her recent monograph with Paula Olszewski-Kubilius and Frank Worrell (2011) is an important new influence. They cited me and I mutually cite them here. [xvi] I have been influenced by the work of the curriculum reconceptualists, especially my friend Patrick Slattery. My article on postmodern curriculum and gifted education is my most downloaded article about gifted education.[xvii] I am also influenced by the arts-based researchers, especially the poetic inquirers. My most downloaded article is an article about poetic inquiry.[xviii] A main partner in creativity workshops and thinking has been F. Christopher Reynolds and I cite our work on depth psychology and giftedness here.[xix] In my latest book, the first I ever edited, I draw on all these threads with the 22 authors who have written personal essays. It is called Organic Creativity in the Classroom: Teaching to Intuition in Academics and the Arts

19. What have we neglected to ask?

Piirto: You neglected to ask me to include a poem. I try to combine both of my avenues of work. For example, I never give a talk without reading a poem. People should know I am both a researcher and an artist. This poem is the title poem of an anthology of women writers with ties to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, published in 2015 from Michigan State University Press (Here, edited by Ron Reikki). It celebrates my ethnicity (Finnish American) and my antecedents.

“ Where is the wanderer’s home?

Runo 34, Kalelvala

at our grandmother’s birthplace

in her very front yard

here my mother, sisters and I

walk the very path

here, very here, this very river

in Vimpeli, Finland

here this yellow round church

here this brown swift river

did she swim in it?

here we her American children

come to see to feel to touch

no, the river runs fast and deep

the very view she saw here

her whole young life

but she was a very good swimmer

this very old church steeple

these new green reeds here

she would swim out to the middle of the lake

float for hours at camp

here in dream time

(after she left at 19

she never returned)

-Poem by Jane Piirto

[i] Piirto, J. (2015). Poems written in service of “service.” In K. Galvin and M. Prendergast (Eds.). Poetic inquiry II: Seeing, caring, understanding (pp. 124-148). Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

[ii] Piirto, J. (2016). The Five Core Attitudes and Seven I’s for enhancing creativity in the classroom. In J. Kaufman and R. Beghetto (Eds.). Nurturing creativity in the classroom, 2nd Ed. (pp. 142-171). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

[iii] Piirto, J. (2016). The creative intelligence of teachers resisting the Pearsonizing of global education. In D. Ambrose & R. Sternberg (Eds.). Creative intelligence in the 21st Century: Coping with enormous problems and huge opportunities (pp. 139-158 ). Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

[iv] In press. Piirto, J. The creative process in writers. In T. Lubart, (Ed.). The Creative Process: Perspectives from multiple domains. Palgrave Macmillan.

[v] Piirto, J. & Fraas, J. (2012). A mixed-methods comparison of vocational and identified gifted high school students on The Overexcitability Questionnaire (OEQ). Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 35(1), 3-34.

[vi] Piirto, J. (2010). 21 years with the Dabrowski Theory: An autoethnography. Advanced Development Journal.

[vii] Piirto, J. (2002). Motivation is all. Then they can do anything. Qualitative portrait of a school for the gifted and talented in India. Gifted Child Quarterly, 46(3), 181-192.

[viii] Piirto, J. (2000). Krishnamurti and me: Meditations on India and on his philosophy of education. Journal for Curriculum Theorizing, 16 (2), pp. 109-124. Reprinted in Piirto, J. (2008). Krishnamurti And me: Meditations on his philosophy of curriculum and on India. In C. Eppert and H. Wong (Eds.). Cross-cultural studies in curriculum: Eastern thought, educational insights (pp. 247-266). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum.

[ix] Piirto, J. (2004). Understanding creativity. Tucson, AZ: Great Potential Press.

[x] Piirto, J. (2007). Talented children and adults: Their development and education, 3rd ed. Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

[xi] Piirto, J. (1992). Understanding those who create. Dayton, OH: Ohio Psychology Press. Also translated into Chinese.

[xii] Piirto, J. (1994). Talented children and adults: Their development and education. New York, NY: Macmillan/Merrill.

[xiii] Piirto, J. (2011). Creativity for 21st Century Skills: How to embed creativity into the curriculum. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

[xv] Piirto, J., & Keller-Mathers, S. (2014). Mary M. Meeker: A deep commitment to individual differences (1921-2003). In A. Robinson and J. Jolly (Eds.), Illuminating lives: A century of contributions to gifted education (pp. 277-288). New York, NY: Routledge.

[xvi] Subotnik, R., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Worrell, F. (2011). Rethinking giftedness and gifted education: A proposed direction forward based on psychological science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 12, 3–54.

[xvii] Piirto, J. (1999). Implications of postmodern curriculum theory for the education of the talented. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 22 (4), 386-406. Reprinted in Mensa Research Journal, 39(1), 19-38.

[xviii] Piirto, J. (2002). The question of quality and qualifications: Writing inferior poems as qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 15 (4), 431-445. Reprinted in C. Leggo, P. Sameshima, and M. Prendergast (Eds.), Poetic inquiry: Vibrant voices in the social sciences (pp. 83-109).. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers

[xix] Reynolds, F., & Piirto, J. (2005). Depth psychology and giftedness: Bringing soul to the field of talent development education. Roeper Review, 17, 164-171. Reynolds, F. C., & Piirto, J. (2007). Honoring and suffering the Thorn: Marking, naming, initiating, and eldering: Depth psychology, II. Roeper Review, 29(5), 48-53. Reynolds, F. C., & Piirto, J. (2009). Depth Psychology and integrity. In T. Cross and D. Ambrose (Eds.). Morality, Ethics, and Gifted Minds (pp. 195-206). New York, NY: Springer Science